Sand rivers (15 page)

Amboseli had also been turned into near-desert, though the removal of the Maasai cattle, together with the years of rain, restored the vegetation, and all of the animals substaatjally recovered - except the rhino, of which there were just ten left. Both Samburu and Meru were seriously beset by poachers, and for several years such northern species as the Grevy zebra and reticulated giraffe were in danger of extinction. Even the Mara, though still prosperous, was invaded by rhino and leopard poachers, and was also threatened because much of it was suitable for growing wheat; north of the Mara, the Mau Mountains were being deforested and the animals killed off by farmers.

"Kenya's population is still shooting up, fastest in Africa," Rick Bonham told me, "and they'll all want land, and the white man's lands have already been taken." He shrugged his shoulders. "I see Africa deteriorating every year, this kind of life, at least." He gazed out over the Luwegu toward the blue hills beyond. "It's such a delicate balance, you see, especially when the governments are so unstable. It's the human population, if nothing else; there's not enough room, so the animals have got to go. That's why my family insisted that I get my commercial pilot's license; I'll have that piece of paper just in case the wildlife situation falls apart and there is no more hope for this safari business."

It was as a pilot for a Nairobi charter outfit, on a three-month job in the Sudan, that Rick got to know another pilot named Brian Nicholson, who spoke to him often and longingly of the Selous; in some ways, this ex-warden reminded him of his father, and he was grateful to Brian for having recommended his new safari company to Tom Arnold. For Rick, as for Hugo and for me, the Selous was a symbolic place, "the last stronghold", as Rick put it, of the wildlife of East Africa. "I'm just happy to be out in the real bush. In Kenya, I don't miss the hunting much except for bird shooting, and that surprises me, because for a while there.

PETER MATTHIESSEN

hunting was my life. On the other hand, I kind of enjoy this chance to go out and shoot the odd animal for the pot."

1 asked Rick what he thought of the Kenya Wildlife Clubs, started as a school program in the early 1970s by a young American named Sandra Price (and recently extended to Uganda and Tanzania). "Doing a fantastic job," said Rick. "That's the only hope. Those kids marched on Nairobi during the campaign to close down the damned curio shops, and they made a hell of a difference. More and more these days you hear Africans talking about wildlife with real feeling. It really means something to them. It isn't just nyama (meat) any more." Since the arrival of the safari in the Selous, Rick had gained weight and color, and at this moment he spoke with rare animation. Then he shrugged, gazing out over the swift Luwegu. "I'm afraid I'm a bit pessimistic," he said. "The Selous is really the last hope."

The man in charge of Rick Bonham's equipment was a former elephant hunter and tracker named Kirubai, one of a number of Kenyans who lost a former way of life with the ending of hunting safaris in his own country. Kirubai still served as a tracker when Rick went out to stalk buffalo to feed the camp, and one morning I accompanied them on a short expedition to the far side of the Mbarangandu, where they hoped to find a few guinea fowl for the sahibs' table. But the guinea fowl, so common and noisy when not needed, were off in the thickets keeping their own counsel, and we took time to observe instead the beautiful Boehm's bee-eater, the crowned hornbill, and a beautiful small falcon called Dickinson's kestrel, none of which I had seen before in the Selous.

Eventually Rick shot a dove, and Kirubai, who had collected and discarded a whole series of small sticks, shaved one to a dull point, then pressed this point into the flat shaved surface of another. Using a pinch of the sandy soil for friction, he spun the upright stick between his hands with such concentration that sweat leapt out on his creased brow. When a shallow hole was made, he cut a nick in the bottom stick so that the sawdust could spin out; the spinning continued until smoke appeared, with the spark that would light a tinder of dry grass tucked in below. The dove was skewered on another long stick sharpened at both ends, with the heavier end stuck into the ground at just the angle to suspend the bird a few inches above the embers.

Contentedly, observing hippos in a small river lagoon just beneath us, we cut the dove into three pieces and ate it in the sun, as Kirubai exclaimed over and over at certain subtleties of hippopotamus behavior that heretofore he had not noticed. Rick Bonham thought that Kirubai's experience and ease with the wild animals might have saved his life a few nights before when the truck got mired on its way down here to Mkangira. Kirubai was lying down, digging out the wheel, when he

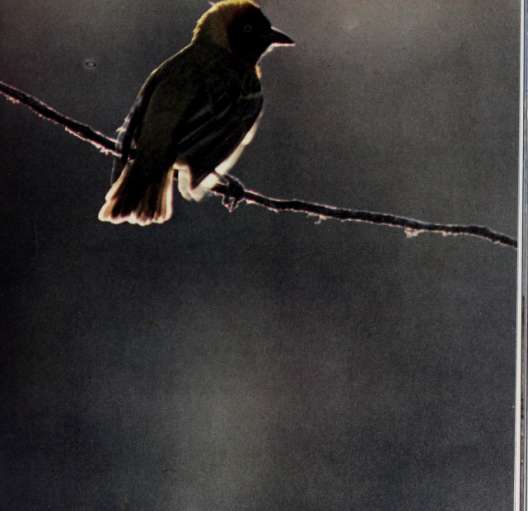

(Ri^t) Masked weaver. 196 1

/

^

%

^m.

-Jti