Sally Heming (44 page)

Authors: Barbara Chase-Riboud

"Why have you not married some woman of your own

complexion?" The Virginia Gazette.

He ground his teeth. Why? "Tell me who die," he

thought, "who marry, who hang themselves because they cannot

marry...." He prayed that Sally had not seen most of what had been written

about them. He came home feeling defeated. Everything reminded him of his two

families and the problems they faced. The presence of Maria and Martha in

Washington last winter had dampened all but the most infamous gossipmongers.

They had not deserted him. He had had his explanation with them and now he must

arrange a meeting with his injured friend and avoid a duel at all cost. He had

already talked his son-in-law Thomas Mann out of a duel with his cousin John

Randolph for the sake of Martha; now Madison must do the same for him. He could

not leave either his white family or his slave family unprotected by his death.

Thomas Jefferson looked up at his slave wife as she entered

his rooms. She appeared terribly small to him and fragile.

She wouldn't know the worst!

The following day James Madison arrived at Monticello. He

was bringing good news. He had interceded in Thomas Jefferson's favor, and

there would be no duel.

"I can't tell you how relieved I am, Mr. Madison, with

the outcome of this unfortunate affair ... and how I thank you."

"Mr. President, I don't think Mr. John Walker was any

more anxious for a duel than you."

"My dear Mr. Madison, I've never even held a pistol in

my hand. The very idea of one man murdering another in the name of injury is

insanity. We already have enough ways of men killing men without inventing an

etiquette for it."

"The law of Virginia 'honor' is a rather crude one,

sir."

"Mostly the law of vanity, dear sir. I am a simple

man. I accept with relief your intervention in this senseless affair and am

quite satisfied that Mr. Walker has accepted my apology."

James Madison noted a slight hesitation. Thomas Jefferson

was anything except a "modest" man and "insanity" or not,

he was a Virginian brought up in its codes and mores. The Walker affair had

distressed him much more than he was willing to admit. And his vanity had

indeed been touched. There was yet one more thing.

"As for the other calumny ..." began James

Madison, "I believe Mr. Monroe would be happy to take her."

Madison couldn't bring himself to say Sally Hemings.

"Take her?"

Thomas Jefferson swayed slightly and the blood rushed from

his face. "Temporarily, of course," added James Madison, alarmed at

the sudden pallor of the man standing before him. "Take her where?"

"Why doesn't she ... I believe ... she has a sister

Thenia at Mr. Monroe's. She could ... retire there with her children until the

time when—"

James Madison raised his eyes from the silver buttons on

Thomas Jefferson's waistcoat and looked directly into his eyes. How could

Thomas Jefferson not know in what political danger he was? He, James Madison,

simply had the duty to warn him that Virginia would not tolerate, even from

Thomas Jefferson, certain unpardonable things. He had to understand.

James Madison involuntarily stepped back. The cold blue

eyes had now turned a deep aquamarine.

"The Hemingses are mine," said Jefferson.

"All of them. I will deal with them personally."

"I didn't mean to presume ..." began Madison. He

concentrated on controlling the tremor in his voice. He brought his

handkerchief out of his waistcoat and mopped his brow. He had gone too far. Too

far for his own good. Relieved, he realized that Thomas Jefferson had already

dismissed the subject. His face had taken on the serene expression Madison knew

so well: his public face. The flash of his inner turmoil had been suppressed.

Thomas Jefferson seemed even taller to Madison as, towering over his small

person, he took him by the shoulder and flashed one of his rare smiles. The

sudden intimacy made Madison blush.

"We have come this far, Mr. Madison. But we still have

a long road to travel... full of the most dangerous ruts for the carriage of

State." Thomas Jefferson's smile disappeared. "You know, Mr. Madison,

how I feel about your rightful place in the political scheme of things….I'm an

old man. Compromise comes hard to me, but you have a brilliant talent for

negotiation. A nation isn't shaped in a featherbed...."

Madison started. It was a strange choice of words, but

Thomas Jefferson didn't seem to notice.

"Shall we get back to the important issues of the day?

Put this demeaning and ridiculous affair behind us. You have a long way to

travel, my dear Madison. After all, we can't disappoint Mrs. Madison, can we?

She's dead set on redecorating the President's House. And God knows, it needs

it!"

Both men laughed.

The night before he left the safety of Monticello for

Washington City, Thomas Jefferson sat alone in his study and brooded on what he

had written in his account book in August

1800.

He knew now that there would be no duel, thanks to the

sturdy and tenacious Madison. Callender could be silenced—the others were mere

copiers. He could end the outcry in the Republican press; if only his friends

could end the clamor in the Federalist press.

He must bring his families through the crisis of Callender

but he must navigate the United States through the bloody aftermath of Napoleon

and the specter of his troops arriving at the Mississippi; he must control an

undeclared war on Tripoli; cope with the Indian boundaries which were

constantly violated as the nation pushed them farther and farther West; he must

reduce the public debt, distribute the surplus in the Treasury—at least, at

last, the slave trade was outlawed; and he must bring to a successful end the

secret negotiations with France for the purchase of Louisiana and mount his

expedition to the Pacific. He had already chosen his secretary, Meriwether Lewis,

as head of the expedition, and he would take back to Washington City his new

secretary, Lewis Harvie, who was loyal enough to have threatened to kill James

Callender.

Callender. His Judas. Sally Hemings was only a pretext.

Before he had left for Washington, he would put down his for all to see. He had

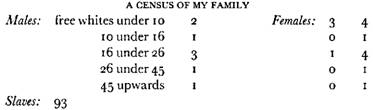

also made a census of his family.

He lit his candle in the darkening study, opened his

account book and wrote:

Shortly after Thomas Jefferson had returned to Washington I

looked at his account book and found the pages open to the census he had

written in it of his family.

I stared at it for a long time, and then softly closed it.

My master had counted Thomas, Beverly, and Harriet as free and white.

Our love had been denounced and we had been betrayed in

Virginia. Even now, the hate, the epithets made me shiver. Did he think I

hadn't heard them all?

Slave, whore,

slut, concubine, Black Sal, Dusky Sally, paramour, blackamoor, wench, a slave

paramour with fifteen or thirty gallants of all colors, including Thomas Paine,

black wench and her mulatto litter, mahogany-colored charmer, Monticellian

Sally, Sooty Sal, black Aspasia ...

nothing was too

horrible for me: my heart cut out, my tongue pulled out by its roots, my body

burned, my throat slit from ear to ear, my soul sent to everlasting Hell.

Perhaps they would at least triumph in sending my soul to Hell, but for the

rest it was too late. My master and I were both anchored to a past and a

passion nothing could disavow. I had prayed for proof and he had given it to

me.

He had paid the worst of all possible prices: public

humiliation. To have been scourged at the public whipping post for slaves would

have been easier for him than that price: the loss of his public image, the facade

he cherished almost as much as he cherished the facade of Monticello.

He had paid. There was something he could do: remain

silent. And this silence would be payment. Payment for my servitude, which he

would not change. Payment for our children, whom he did not recognize. He had

paid with a kind of helpless, bewildered pride, for I was Monticello.

CHAPTER 34

MONTICELLO,

1803-1805

"Familia" did not (originally) signify the

composite ideal of sentimentality and domestic strife in the present day

philistine mind. Among the Romans, it did not even apply in the beginning to

the leading couple and its children, but to the slaves alone. Famulus means

domestic slave and familia is the aggregate number of slaves belonging to one

man.... The expression (familia) was invented by the Romans in order to

designate a new social organism that head of which had a wife, children and a

number of slaves under his paternal authority and according to Roman law, the

right of life and death over all of them.

friedrich engels,

The Origin of the

Family, Private Property, and the State,

1884

God forgive us, but ours is a monstrous system, a wrong and

an iniquity! Like the patriarchs of old, our men live all in one house with

their wives and concubines: the mulattos one sees in every family partly

resemble the white children. Any lady is ready to tell you who is the father of

all the mulatto children in everybody's household but her own. Those, she seems

to think, drop from the sky.

mary boykin chestnut,

A Diary from Dixie,

1840-76

Oh, how can you think of slaves and motherhood! Look into

my eyes, Marianne, and think of love.

kate

C

hopin

, "The Maid of Saint Phillippe,"

1891-92

The news

of the Louisiana

Purchase came like a bolt of thunder at the beginning of the summer. The guns

were fired in Richmond, the bells rang, and there was great rejoicing. The news

of Master Monroe's success in Paris caused a sensation all over the nation and

made him the hero that would someday make him president. My master had doubled

the territory of the United States, purchasing the whole expanse of Louisiana

and the Floridas for fifteen million dollars.

"Typical of Thomas Jefferson," Elizabeth Hemings

declared, not without pride, from the vastness of her kitchens. "He sets

out to buy four acres and a mule, and ends up with a plantation and a herd of

cattle!"

"No, Mama. He set out to buy New Orleans and he has

ended up buying an empire."

Now that we had weathered the worst of Callender and the

Federalist newspapers, it seemed we had reason enough to celebrate. On the

sixteenth of July, the cabinet agreed to the purchase of Louisiana, and on the

seventeenth, Meriwether Jones danced a jig on the west lawn of Monticello. It

was not to celebrate the Louisiana Purchase but to celebrate the death of James

T. Callender. He had been found, dead that morning, in the James River, drowned

in three feet of water.

A year passed. A year free of scandal, although

Monticellian Sally

still rose now

and again in the press.

My master won his re-election by a landslide, losing only

four electoral votes out of one hundred and seventy-six, and not one for Aaron

Burr. It was his moment of greatest triumph, for he knew, if he ever was to

know, that the whole nation loved him. I felt keenly the pleasure of his

triumph. Gone were his protests of disdain, his abhorrence of public office,

his flight from using power. Truly, this outpouring of love and gratitude was

enough to turn the head of a man who, more than anything else, loved to be

loved.