Salem Witch Judge (39 page)

Authors: Eve LaPlante

In Prince’s words, Samuel Sewall was “esteemed and beloved among us for his eminent piety,” “cheerful conversation,” “regard to

justice,” “compassionate heart,” “neglect of the world,” “catholic and public” spirit, “critical acquaintance with the Holy Scriptures in their inspired originals,” “zeal for the purity of instituted worship,” “tender concern for the aboriginal natives,” and, “as the crown of all, his moderation, peaceableness and humility.”

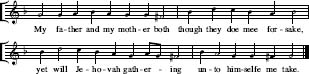

Joseph gave the second sermon, which he titled The Orphan’s Best Legacy. His text was the tenth verse of Psalm 27: “When my father and my mother forsake me, then the Lord will take me up.” Had Samuel been able, he would surely have lined out the psalm for the congregation to sing.

Samuel Sewall had carefully overseen scores of wills in his role as a probate judge, but he died intestate, trusting his two sons agreeably to settle his estate. His mansion went to forty-one-year-old Joseph. Because Joseph chose to remain in the parsonage of the Third Church, he turned over the mansion to his older brother, fifty-one-year-old Sam Jr., who lived in it with his family.

Samuel’s youngest daughter, Judith, the only one of his seven daughters who survived him, was twenty-nine when he died. She died a decade later, at thirty-nine, on December 23, 1740, of unknown causes. Her oldest son, William Cooper Jr., a Boston town clerk, was a prominent Patriot in the Revolution, one of whose great-grandsons was Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., a justice of the Supreme Court of the United States. Judith’s second son, the Reverend Samuel Cooper, preached at the Brattle Square Church like his father and was a founder of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Sam Jr. and Joseph were the only Sewall offspring who enjoyed old age. In December 1738 Sam Jr. asked the Massachusetts House of Representatives to appoint a committee to determine “the circumstances of the persons and families who suffered in the calamity of the times in and about the year 1692.” Samuel’s son “entered into the matter with great zeal,” the historian Charles Upham noted, and the court unanimously supported his order. As head of the committee then

formed, Sam Jr. wrote letters asking his cousin Mitchell Sewall, of Salem, Stephen’s son, and John Higginson, whose father had participated in the hunt until the accusation of his wife, to help the cause. As a result of these and other efforts, Governor Jonathan Belcher in November 1740 determined to “inquire into the sufferings of the people called Quakers…and also into the descendants of such families as were in a manner ruined in the mistaken management of the terrible affair called witchcraft. I really think there is something incumbent on this government to be done for relieving the estates and reputations of the posterities of the unhappy families that so suffered….”

Sam Jr. died at the Sewall mansion in Boston in 1751 at seventy-two, survived only by his son, Henry. Henry inherited the Sewall farm in Brookline, which extended from what is now the western campus of Boston University to Fenway Park and the Muddy River in the Longwood Medical Area. Tens of thousands of people, including me, now live on this land.

Joseph was the most enduring Sewall child, living until he was eighty, even longer than his father had. Joseph served a “long and mostly serene” ministry at the Third Church. At the end of his life he supported colonial America’s independence from England and allowed the Third Church to become “a shrine of the American cause.” He preached into his eightieth year and died on June 27, 1769, survived by only one of his and Elizabeth’s two sons, Samuel (1715–1771). That Samuel Sewall married his distant cousin Elizabeth Quincy, the sister of John Hancock’s wife, Dorothy. They too had a son, Samuel Sewall, who, like his great-grandfather, attended Harvard (class of 1776) and grew up to be chief justice of the Superior Court of Judicature. That Judge Samuel Sewall’s son the Reverend Samuel Sewall, of Burlington, Massachusetts, in the nineteenth century donated the diaries and letters of his great-great-grandfather to the Massachusetts Historical Society, where they remain.

Another great-grandchild of Joseph Sewall was my great-great-great-grandfather the Reverend Samuel Joseph May (1797–1871), a Unitarian minister and abolitionist. The Reverend May (Harvard class of 1817) noted defensively in his memoir that our ancestor participated in the Salem witch trials only “as a junior judge.” He “was among the first to suspect, and afterward to expose, the delusion” of

the witch hunt, and he “strove in so many ways to atone for that early wrong.” The “early” suggests Sewall’s youth, but the Reverend May must have known that in 1692 Sewall was forty years old.

Samuel Joseph May’s sister, Abigail May Alcott (1800–1877), was the mother of Louisa May Alcott, another lineal descendant of Samuel Sewall. The May and Sewall families had merged in 1784 with the wedding of Colonel Joseph May (1760–1841), a founder of Massachusetts General Hospital, and Dorothy Sewall, a great-granddaughter of Samuel Sewall through his son Joseph.

Repentance was the subject of a sermon that the Reverend Joseph Sewall addressed to the governor and council of New England at Boston’s Town House on December 3, 1740. Addressing the passage in the Old Testament Book of Jonah in which Jonah warns the city of Nineveh of its need to repent, Joseph Sewall envisioned Jonah walking around the present world warning people to repent. “No greatness or worldly glory will be any security against God’s destroying judgments,” Samuel’s son preached, “if such places go on obstinately in their sins. O let not London! Let not Boston, presume to deal unjustly in the land of uprightness, lest the holy God say of them, as of his ancient people,…‘I will punish you for all your iniquities.’” The king of Nineveh “humbled himself before the most high” and “arose from his throne, and laid his robe from him, and covered him[self] with sackcloth, and sat in ashes.”

Joseph Sewall continued, “We must believe our Lord Jesus when he says to us, Except ye repent, yet shall all likewise perish.…We must abhor ourselves, lie down before God in deep abasement, and humble ourselves under his mighty hand.” Finally, he assured his listeners, quoting Ezekiel, “A new heart also will I give you, and a new spirit will I put within you, and I will take away [your] stony heart…and I will give you a heart of flesh….” It is hard to imagine that this sermon, “Nineveh’s repentance and deliverance,” was not inspired by Joseph’s father.

More than a century later the historian Charles Upham closed his seminal study of the witch hunt, Salem Witchcraft (1867), with the story of Samuel Sewall. Having traversed “scenes of the most distressing and revolting character,” Upham wished to “leave before your imagination one [scene] bright with all the beauty of Christian

virtue.” That was “Judge Sewall standing forth in the house of his God and in the presence of his fellow-worshippers, making a public declaration of his sorrow and regret of the mistaken judgment he had cooperated with others in pronouncing. Here you have a representation of a truly great and magnanimous spirit,” which had achieved a “victory over itself; a spirit so noble and pure, that it felt no shame in acknowledging an error, and publicly imploring, for a great wrong done to his fellow-creatures, the forgiveness of God and man.”

Upham warned, “Elements of the witchcraft delusion of 1692 are slumbering still,” and “always will be…. The human mind feels instinctively its connection with a higher sphere. Some will ever be impatient of the restraints of our present mode of being, and…eager to pry into the secrets of the invisible world, willing to venture beyond the bounds of ascertainable knowledge, and…to aspire where the laws of evidence cannot follow them.” Or, as the twentieth-century historian Keith Thomas observed, “If magic is to be defined as the employment of ineffective techniques to allay anxiety when effective ones are not available, then…no society will ever be free from it.”

Rectifying the wrong of the witch hunt took centuries and remains incomplete. Not until 2001 were the last five victims of the Salem witch hunt exonerated. The legislative act to pardon Susanna Martin, Bridget Bishop, Alice Parker, Margaret Scott, and Wilmot Reed was signed that year on Halloween by Massachusetts governor Jane Swift, John Winthrop’s first female successor. “The fear of malefic witchcraft is still a problem in many parts of the world,” the historian Marilynne Roach noted in 2002. Witchcraft executions occurred in Switzerland as late as 1782, in Germany until 1793, and in Mexico in the twentieth century. Even today “neighbors and witch-finders in Africa, India, Slovakia, the Ukraine, and elsewhere blame suspects—often women—for causing local misfortunes,” Roach noted. During the last decade of the twentieth century, for instance, authorities in Bihar, India, killed more than four hundred suspected witches.

Samuel Sewall’s world is less distant than it seems. We too may never transcend superstition and misjudgment. Yet he can be our guide in acknowledging and rectifying our wrongs. Like him, we are capable of a change of heart.

EXPLORING SAMUEL SEWALL’S AMERICA AND ENGLAND

Although he was peripatetic for his day, thrice crossing the Atlantic Ocean, Samuel Sewall never traveled far beyond southern England, where he was born, and Massachusetts, where he spent most of his life. In sixty-eight years in New England he rode or sailed only as far north as Maine’s Kennebec River, as far west as Albany, New York, and as far south as Manhattan. As a result of this—and his frequent, detailed diary entries—it is not hard for us to follow his steps.

Samuel’s favorite place on earth, where he envisioned the Second Coming of Jesus Christ, was the Great Marsh on Massachusetts’s North Shore. Much of New England’s coastal wetlands have been destroyed to make way for cities and suburbs. But the Great Marsh is still there, protected by the federal government and local groups as a wildlife preserve. As a result, the Great Marsh provides a rare glimpse of Samuel’s seventeenth-century world.

An edge of the Great Marsh can be seen from a car on Interstate 95 just north of the Scotland Road, Newbury, exit. For a closer look, visit Perley’s Marina, a boatyard along the Rowley River just south of Newbury. Perley’s sells fishing tackle, worms, and cold drinks. Nautical maps

of the Rowley River, Ipswich Bay, and Plum Island Sound plaster the walls. On the hot July morning that I explored these waters with a local fisherman, the greenhead flies were biting, especially at the low speed required near shore. (They bothered Samuel, who also reported “much affliction…by the mosquitoes” on the Maine coast in August 1717.) A few hundred yards east of Perley’s Marina the Rowley River passes under the bridge that conveys the Boston-Newburyport commuter rail. Just beyond the bridge the Great Marsh opens up and spreads out. Water, sky, and marsh grass predominate. A few duck-hunting cabins and houses on stilts, accessible only by boat, dot the marsh. That morning an osprey flew overhead. In the mud beside the estuary a snowy egret dug for food.

A mile or so east of the marina the river meets Plum Island Sound, the warm, calm, shallow bay that is protected by the slender, sandy strip of Plum Island. The sound teems with blue fish, sea bass, cod, haddock, flounder, and mackerel. A few herring remain, but the sturgeon, which were plentiful in Samuel’s day, are gone. From a boat in the middle of Plum Island Sound, you can roll back the centuries. With the exceptions of thickly settled Ipswich Neck and occasional structures in the Rowley marsh, this landscape bears almost no sign of European settlement. The view is remarkably like what Samuel Sewall saw from here as a boy and remembered as a man. It is not unlike Governor John Winthrop’s first view of Boston, from Charlestown in the summer of 1630. Most of the city we know as Boston was then underwater at high tide, including the land beneath Faneuil Hall, Quincy Market, the Prudential and John Hancock buildings, the Public Garden, Massachusetts General Hospital, the Back Bay, and the South End. The Great Marsh now conveys an image of coastal New England when it was inhabited only by Native American tribes.

Two-thirds of Plum Island—accessible by boat or a bridge at its northern end—is a nature preserve. The unprotected, northern third of the island is thickly settled, crowded with summer homes and convenience stores. A single road leads south to the preserve, which is populated by scrub pines and junipers, great blue herons, and occasionally a glossy ibis. In the 1950s the federal government banned all development on this part of Plum Island and restricted owners of existing houses from altering them, selling them, or bequeathing them

to anyone but a direct heir. As the final heir of each house died, the government razed it. By the early twenty-first century only one house remained in the preserve, a wind-worn Victorian with a wraparound porch overlooking a grassy lawn and private dock. The house belonged to a childless man in his nineties who still swept the sidewalk in front of a Rowley gas station, which he owned.

Duck hunters were the intended beneficiaries of the federal government’s action on Plum Island, according to Kathryn Glenn, an official of the Massachusetts Office of Coastal Zone Management. “Migratory birds use Plum Island as a flyway, which the federal government saved, to protect ducks for hunting.” Local environmental groups soon became involved and the philosophy changed. Now the birds—and landscape—are saved for themselves. In the wake of the preservation of most of Plum Island, the Essex County Greenbelt Association, Massachusetts Audubon Society, and Trustees of Reservations collaborated with local officials to protect a much larger swath of the North Shore. Locals now refer to a Great Marsh spanning seventeen miles of the northern Massachusetts coast, from Salisbury on the New Hampshire border south to West Gloucester.