Sacre Bleu (6 page)

“We can’t even give them away,” said Pissarro forlornly.

“Nonsense,” said Père Lessard. “The winner simply hasn’t shown yet. And all the better if they don’t. You have the ten

francs

we got for selling the tickets, and your magnificent painting will hang in my bakery where the people may admire it.”

“But, Papa—” said Lucien, who was about to correct the arithmetic when Father shoved a buttered roll in his mouth. “Mmmpppf,” Lucien continued with a spray of crumbs. After all, the tickets had only sold for a

sou

each, with twenty

sous

to the

franc,

and they’d only sold seventy-eight tickets—why, it was less than four

francs!

And Lucien would have said so if his father hadn’t muzzle-loaded him with

un petit pain

while handing a ten-

franc

note across the table to Pissarro.

Across the square a donkey brayed, and they turned to see a bent little brown man in an ill-fitting suit trudging up the street, leading the donkey, but their attention was immediately captured by the girl who walked but ten paces ahead. Lucien’s mouth fell open and a ball of half-chewed bread tumbled out of his mouth onto the cobbles. Two pigeons in the square cackled at their good fortune and made a fast walk for the gift from above.

“I’m not too late, am I?” the girl called. She held her raffle ticket before her.

She couldn’t have been more than fifteen or sixteen, a delicate thing in a white dress with puffy sleeves and great ultramarine bows all down its front and at the cuffs. Her eyes matched the bows on her dress, too blue, really, and even the painter, a theorist and student of color, found he had to look a bit askew at her to keep from losing his train of thought.

Père Lessard stood and met the girl with a smile. “You are just in time, mademoiselle,” he said with a bit of a bow. “May I?”

He plucked the ticket from the girl’s hand and checked the number. “And you are the winner! Congratulations! And how lucky it is that the great man himself is here. Mademoiselle…”

“Margot,” said the girl.

“Mademoiselle Margot, may I present the great painter, Monsieur Camille Pissarro.”

Pissarro stood and bowed over the girl’s hand. “Enchanted,” he said.

Lucien, who was, indeed, enchanted—thought she might be the single most beautiful thing he had ever seen—stared at her, wondering if Minette, in addition to learning to be spiteful, might someday wear a dress with blue bows, and if her voice might take on the sound of a music box like Margot’s, and her eyes sparkle with laughter, and if so, he would have her sit on the divan and he would just look at her without blinking, until water came to his eyes. He didn’t know that it was strange for the sight of one girl to inspire love to the point of tears for another, because Minette had been his only love, but there was no question that the sight of Mademoiselle Margot had opened his heart for Minette so it felt like it might leap out of his chest with joy.

“Come inside, mademoiselle,” said Père Lessard, deftly slipping his hand under Lucien’s chin and closing the boy’s mouth. “See your painting.”

“Oh, I have seen it,” Margot said with a laugh. “And I was wondering if instead of the painting, I might have one of your sticky buns as my prize.”

The smile with which Pissarro had greeted the girl fell as if he’d been suddenly shot in the face with a paralyzing dart of Pygmy art critics from the darkest Congo. He sat down as if suddenly exhausted.

“I’m teasing,” said Margot, touching Pissarro’s sleeve coquettishly. “I am honored to have one of your paintings, Monsieur Pissarro.”

The girl followed Père Lessard into the bakery, leaving Pissarro and Lucien outside, both a little stunned.

“You, Painter,” came a scratchy voice. “Do you need colors? I have the finest hand-ground pigments.” The twisted little man and his donkey had moved to the side of the table.

Pissarro looked up to see the little man waving a tin tube of paint in the air, the cap off.

“The finest ultramarine,” said the Colorman. “Real color. True color. Cinnabar, madder, and Italian earths. None of that false Prussian shit.” The little man spat at the pigeons to show his disdain for Prussians, man-made colors, and, in general, pigeons.

“I get my colors from Père Tanguy,” said Pissarro. “He knows my palette. And besides, I have no money.”

“Monsieur,” said Lucien. He nodded to the ten-

franc

note, which Pissarro still held in his hand.

“Just try some ultramarine,” said the Colorman. He capped the tube of paint and set it on the table. “If you like it, you pay. If not, no worry.”

Pissarro picked up the tube of paint, uncapped it, and was sniffing it when Margot emerged from the bakery, dancing the small canvas in a great circle in front of her, her skirts swirling around her as she moved. “Oh, it’s wonderful, Monsieur Pissarro. I love it.” She held the canvas to her breast, bent, and kissed Pissarro on top of his bald head.

Lucien felt his heart leap with the lilt in her voice and he blurted out, “Would you like to see a picture of dogs wrestling?”

Margot turned her attention to Lucien now, and still clutching the painting to her bosom, she caressed his cheek and looked into his eyes. “Look at this one,” she said. “Oh, these eyes, so dark, so mysterious. Oh, Monsieur Pissarro, you should paint a portrait of this one and his deep eyes.”

“Yes,” said Pissarro, who suddenly realized that he was holding a tube of paint and the twisted little man and his donkey were gone.

Lucien didn’t remember seeing him leave. He didn’t remember the girl leaving, or going on to school, or his lessons from Monsieur Renoir. He didn’t remember anything that happened for the next year, and when he did remember again, he was a year older, Monsieur Pissarro had painted his portrait, and Minette, the love of his young life, was dead from fever.

It was a small enchantment, really, Lucien’s encounter with the blue.

“These dogs are not fighting, Rat Catcher.”

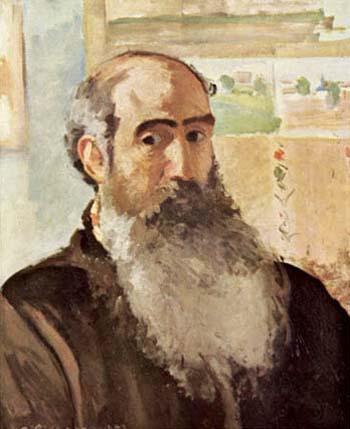

Self-Portrait

—Camille Pissarro, 1873

1890

I

LIKE A MAN WITH TWO STRONG EARS,” SAID

J

ULIETTE.

S

HE HAD

L

UCIEN BY

the ears and was pumping his head back and forth as if to make sure that his ears had been nailed on properly. “Symmetry, I like symmetry.”

“Stop it, Juliette. Let go. People are looking.”

They sat on a bench across from the cabaret

Le Lapin Agile,

a small vineyard at their back, the city of Paris spread out before them. They had made their way up the winding rue des Abbesses, looking from each other’s eyes only in glances, and although the day was warm and the climb steep, neither was out of breath or sweating, as if a cool pool of afternoon had opened just around the two of them.

“Well, fine then,” said Juliette, turning away from him to pout. She popped open her parasol, nearly poking him in the eye with one of its ribs, then slouched and puffed out her lower lip at the city. “I was just loving your ears.”

“And I love

your

ears,” Lucien heard himself say, wondering, even though it was true, why he was saying it. Yes, he loved her ears; loved her eyes, as crisp and vibrant blue as the virgin’s cloak; loved her lips, pert and delicate platform for a perfect kiss. Loved her. Then, since she was looking out over the city and not at him directly, the question that had been circling in his mind all afternoon, only to be chased away by his enchantment with her, finally lit on his tongue.

“Juliette, where in the hell have you been?”

“South,” she said, her gaze fixed on Eiffel’s new tower. “It’s taller than I thought it would be when they started it.” The tower had been barely three stories tall when she had disappeared.

“South? South?

South

is not an answer after two and a half years without a word.”

“And west,” she said. “It makes the cathedrals and palaces look like dollhouses.”

“Two and a half years! Nothing but a note saying

‘I’ll return.’”

“And I have,” she said. “I wonder why they didn’t paint it blue. It would be lovely in blue.”

“I looked everywhere for you. No one knew where you had gone. They kept your job open at the hat shop for months, waiting for you.” She had worked as a milliner, sewing women’s fine hats, before she had gone away.

She turned to him now, leaned in close and hid them both behind the parasol, then kissed him, and just when he felt his head start to spin, she broke off the kiss and grinned. He smiled back at her, forgetting for a moment how angry he was. Then it came back to him and his smile waned. She licked his upper lip with the tip of her tongue, then pushed him away and giggled.

“Don’t be angry, my sweet. I had things to do. Family things. Private things. I’m back now, and you are my

only

and my

ever.”

“You said that you were an orphan, that you had no family.”

“That was a lie, wasn’t it?”

“Was it?”

“Perhaps. Lucien, let’s go to your studio. I want you to paint me.”

“You hurt me,” Lucien said. “You broke my heart. The pain was such that I thought I would die. I didn’t paint for months, I didn’t bathe, I burned the bread.”

“Really?” Her eyes lit up the way the children’s did when Régine set out the fresh pastries in the bakery.

“Yes, really. Don’t sound so gleeful about it.”

“Lucien, I want you to paint me.”

“No, I can’t, a friend has just died. I should look after Henri and talk to Pissarro and Seurat. And I have a cartoon I must do for Willette’s

La Vache Enragée

journal.” The truth was, he had more pain to vent on her, and he didn’t want to leave her side for a moment, but he needed her to suffer. “You can’t just pop back into my life from a street corner and expect—and what were you doing on avenue de Clichy in the middle of the day, anyway? Your job—”

“I want you to paint me nude,” she said.

“Oh,” he said.

“I mean, you can leave your socks on, if you’d like.” She grinned. “But other than that, nude.”

“Oh,” he said. His brain had seized when she’d mentioned painting her nude.

He really wanted to remain angry, but somehow he had come to believe that women were wondrous, mysterious, and magical creatures who should be treated not only with respect but with reverence and even awe. Perhaps it was something that his mother used to say to him. She would say, “Lucien, women are wondrous, mysterious, and magical creatures, who should be treated not only with respect but with reverence, perhaps even awe. Now go sweep the steps.”