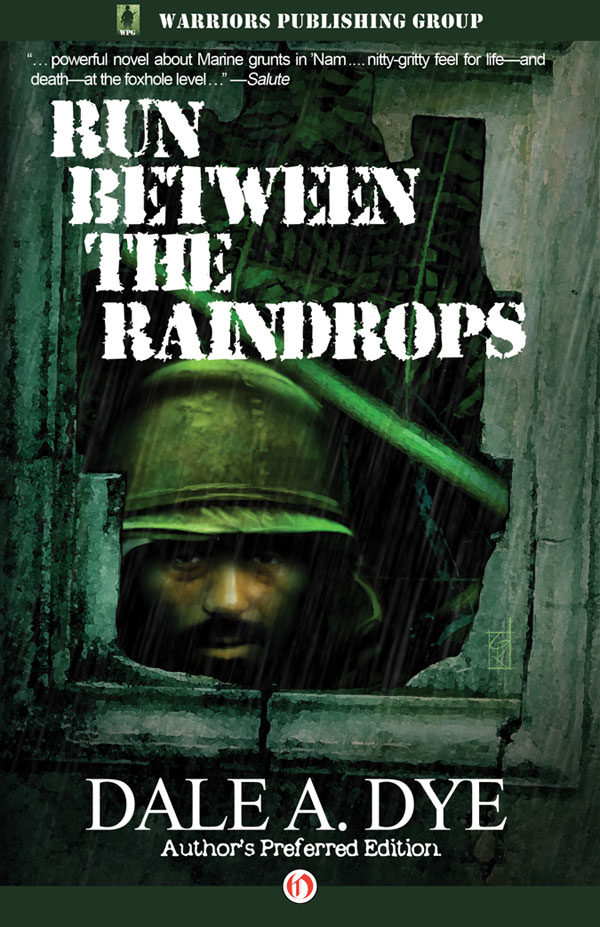

Run Between the Raindrops

Read Run Between the Raindrops Online

Authors: Dale A. Dye

RUN BETWEEN THE RAINDROPS

DALE A. DYE

Author’s Preferred Edition

WARRIORS PUBLISHING GROUP

NORTH HILLS, CALIFORNIA

To the gallant Marine grunts who fought and won the Battle of Hue City. Even after all these years, it's still an honor to stand in your dwindling ranks.

Author’s Foreword

This book began in the worst possible way for some of the best possible reasons. That’s a fairly evocative comment to make about a work published some 25 years ago to scant critical notice and lukewarm sales that barely covered my meager author’s advance, so I’ll take the opportunity of this resurrection to render some thoughts on my first novel.

Ironically, action on this book began on Okinawa, that far eastern island that served as launching point for so many of us who wound up in Vietnam anytime from about 1965 through the end of war ten years later. I was in a fairly stable three-year tour of duty out there having committed to a career as a U.S. Marine and managed to wangle a commission from the enlisted ranks. In a nod to upward mobility, I followed the urging of then Staff Sergeant Maggie Chavez, my wife at the time, and began pursuing a college education. It was a truly wonderful experience, but I was too ignorant to appreciate Maggie forcing me into a consciousness-raising pursuit that paid huge dividends later. Thanks, Maggie. And I’m truly sorry it took me until now to say that.

Another person I need to thank for the experience at the University of Maryland’s University College out there on The Rock is Dr. George Sidney, who was my English professor and later became my literary mentor. George was a scrawny little guy with a big brain and heart to match. It was hard for me to credit the fact that he’d been a Marine rifleman during the bitter fighting in Korea, but he’d come through the Chosin Reservoir campaign and even wrote a book about his experiences. And that’s what tripped the trigger and launched the initial effort to write about some of my own wartime experiences.

We were within sight of my baccalaureate degree in English Lit and looking for something that would grant me a final fistful of credits needed when George started talking about his war experiences and how difficult it had been for him to write about them. He spoke about some of the scenes in his book and they sounded so like things I’d seen in Vietnam that I couldn’t keep my big mouth shut. “I should write a book about Nam.”

George squinted at me and pondered for a moment. It wasn’t the first time we’d shared wartime horror stories, but it was the only time I’d mentioned wanting to write about it. “If you do,” he said picking at the label on a bottle of Kirin Beer, “and if it’s as good as some of your other writing, I’ll check the blocks and grant you the degree requirements.”

With multiple Vietnam tours under my belt between 1965 and 1970, each with their own ample dosages of unique experience and colorful characters, it was clear to me in the planning stages that I was going to have to narrow the focus. To do that, I simply had to open the flood gates and let the images flow from where they’d been dammed up in memory. Nothing crystallized as clear and nerve-jangling as three weeks in Hue City during Tet of 1968. It was right then, as I pondered the image of gore-stained Navy Hospital Corpsman binding wounds to get Marines back into the fight raging through Vietnam’s ancient imperial capital, that I came up with the title for this book.

“Ain’t it a bitch?” Doc Toothpick asked me one night toward the end of the battle for the northside. “Seems like making it through this Hue City deal is like trying to run between the raindrops without getting wet.” And there was the title. Now I simply had to write the rest.

Having read most of the greater and lesser war novels as part of my formal education and my abiding interest in all things military, I knew they ran curiously to type. The new guy flush with innocence arrives in a combat unit, meets a colorful cast of characters both princely and pathetic, becomes steeled or unnerved by the brutalities of combat, and either gets his ass blown away or survives, returning to an ungrateful nation that just can’t understand what he’s experienced. I wanted to write something different with trappings and observations on the gonzo model of first person, experiential screeds that would convey the surreal, often hallucinatory images I recalled from fighting in the mean streets of Hue.

It was a scary prospect and I felt the need for reinforcements, so I communicated with my close combat buddy who had fought through most of the Hue City battle until he got riddled with rocket shrapnel. Both of us had harbored delusions of writing The Great American War Novel at one time or another over the years since Saigon fell. We were both writers. We were both angst-riddled and angry. Why not collude and collaborate on a book about Hue?

Why not indeed? And we tried to make it work but our styles, motivations and schedules never quite came into sync. It wasn’t his fault. It was mine for insisting on a departure from conventional storytelling. The more I pondered, the more I became convinced that the tale should be as twisted and torturous as the fighting that formed its core. Historians, journalists, and other chroniclers could deal with the facts of the Hue City fight. I wanted to take readers on a head-trip that jangled, sizzled, and buzzed like a bad acid jag. In my view, the story—or the impact I wanted it to convey—demanded an erratic, staccato style with prose as raw as the scenes it described. That sort of tune could only be played by a one-man band, so writing the novel would be a solo effort.

At this point, the story began to boil, bubble, and come alive. I thrashed away on a typewriter, often working through the night as Maggie got used to wearing earplugs and dealing with the night sweats prompted by recounting some of the most harrowing moments of my life. It was both rewarding and therapeutic. I learned that I’d been suppressing some bad memories that were prompting bad behavior. These days that’s called Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder. Back then I thought it was just the stoic, manly way of dealing with painful experiences about which noble warriors did not speak publically. And I learned that like a resounding, healthy fart, such things are better out than in. Mentally reliving the experiences I recounted in writing “Run Between the Raindrops” didn’t cure me of my war nerves, but it did force me to confront some very lethal demons that would have eventually eaten my soul.

Along the way I learned a lot about novel writing and about the weird way I engage in that lonely pursuit. I’m a very visual guy and what I do is close my eyes, let a scene unspool in vivid, living color, and then do my best to describe the movie I’ve just seen on the inside of my eyelids. Most writers don’t do it that way. But another thing I learned is that I’m not like most writers, which might account for my less than sterling notoriety in literary circles. Writing for most writers I’ve met seems to be a very cerebral exercise. For me, it’s a sort of low-impact PT session. I write with my body as much as my brain. In the course of composing a single novel, I’ve been known to completely wear the letters off a keyboard home row. I also talk to myself quite a bit, sounding out the dialogue and tasting the words. When I’m shouting or screaming in this effort, I’ve been known to frighten small children and set dogs to howling for blocks around the neighborhood.

Fortunately, I’m fairly facile with language, but when I handed in a first draft to Dr. George Sidney, he thought it was too stilted. George felt I was over-structured and confining myself with conventional prose. “You’ve got to let it flow from your mind, onto the paper and into the imagination of the reader.” George thought it might be a good drill if I went back through the manuscript and tried to eliminate the first-person pronouns. I did that—mostly to appease him—and it turned out to be a brilliant exercise. Suddenly sentence structure lost its sharp edges and rounded into a burbling stream of consciousness. It was the key that popped my story-telling instincts wide open and allowed me to include some very, very personal and painful elements that I’d been afraid to expose in the initial telling.

That doesn’t mean “Run Between the Raindrops” can’t be improved. It’s full of literary naiveté and writing blunders that I would neither make nor tolerate these days. I’m a better writer—or at least more practiced at it—than I was back when I first composed this book. I’ve completed and published seven other novels since and learned a great deal from writing each of them. My prose is less derivative now that I’ve found my own voice, although I still tend to wield words like a meat-axe. I understand now that story-telling is an art that improves with age and practice. So, in that more polished voice and with nearly a half-century of distance at hand, I’ve consented to take a second look at this book, smooth some literary bumps, and try to improve the product.

It’s been difficult to edit by revisiting those mind-numbing experiences in Hue, but I believe now as I did back on Okinawa many years ago that the gain is worth the pain. Some of that has to do with the war stories I hear these days from veterans of the fighting in Iraq and Afghanistan. Likely because these vets know I’ve seen the elephant and heard the owl, they open up to me and describe some of their own most seminal experiences in combat. And many of their stories contain the same sort of surreal, shocking elements that I recall so vividly from the battle for Hue City back in 1968. There’s a common denominator there that needs to be explored and explained to ensure this new generation of veterans doesn’t experience the ignorance and ennui we did on return from our war in Vietnam. If some of these folks read “Run Between the Raindrops,” they may see that common bond and realize their situation is hardly unique. Painful memories and haunting images are part of the dues you pay to play in the deadly and desperate game of mortal combat.

If you’ve not read the book, I hope you enjoy this version. If you’re one of the few who read it when it was released back in 1984, I hope you’ll take another look and follow me once again, step by painful step, through the mean streets of Hue City during Tet 1968. Either way, I’m genuinely glad for your company.

Prologue

Most of the emotion-drunk survivors in the belly of this vibrating beast are higher than whatever the instruments in the cockpit indicate. Most of them are out of it one way or another. This Flying Tiger is removing mostly-whole bodies from the Land of the Lotus Eaters and that’s a huge jolt to the collective pulse. There’s an energy surge that seems to sweep and spark through long rows of uniformed bodies strapped into narrow seats. Layered over the hum of the engines propelling this big silver cylinder out over the South China Sea is a counterpoint of young male voices singing excitedly of plans and expectations.

They run curiously to type, these young American males with dark leathery tans running from the neck up and the elbows down where skin shows through unfamiliar dress uniforms. Random seatmates become best buddies as they share plans to tear The World a new asshole beginning immediately after landing. But that’s 14 hours from now, a tiny tick in time compared to 12 months or more in The Nam. They will endure, calling on long practice in dealing with things in-county that they could not change regardless of how hard they wished or prayed.

A sweaty soldier at my elbow wearing a Purple Heart under aircrew wings wants to show off an album he compiled flying as a door gunner with the 1

st

Cav. He’s chatty and chipper, providing detailed descriptions of the rice paddies and jungle-covered mountains he snapped from his seat in a Huey. There’s even an aerial shot of the Citadel in Hue. He wants to talk about that. No way…not yet…too soon.

Searching for distraction I just nod and stare at scudding clouds outside the window. Door Gunner turns on the man sitting at his other elbow, a truck driver that wants to talk about a convoy ambush somewhere north of Danang. They play one-up with each other while I stuff stereo earphones into my head and click through recorded tunes. There’s some Motown. Philly Dog would dig it but he’s dead, cut down with his buddy Willis on the walls of the Citadel. Country channel blares with somebody singing about a ring of fire. Same song the Southerner used to sing off-key through his crooked nose, but Reb is gone, chopped nearly in half by some faceless gook gunner in Hue City. Janis Joplin strikes a chord: Nothin’ left to lose. That’s freedom.