Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness (91 page)

Read Ross & Wilson Anatomy and Physiology in Health and Illness Online

Authors: Anne Waugh,Allison Grant

Tags: #Medical, #Nursing, #General, #Anatomy

Functions

The fluid that fills the conjunctival sac is a mixture of tears and the oily secretion of tarsal glands, which is spread over the cornea by blinking. The functions of this fluid include:

•

washing away irritating materials, e.g. dust, grit

•

the bactericidal enzyme lysozyme prevents microbial infection

•

its oiliness delays evaporation and prevents drying of the conjunctiva.

Sense of smell

Learning outcome

After studying this section you should be able to:

describe the physiology of smell.

The sense of smell, or

olfaction

, originates in the nasal cavity, which also acts as a passageway for respiration (see

Ch. 10

).

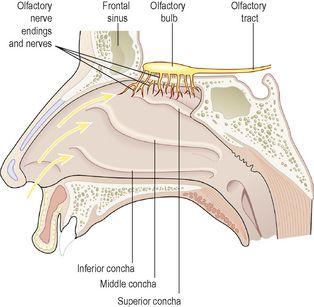

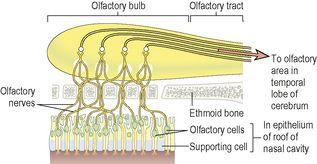

Olfactory nerves (first cranial nerves)

These are the sensory nerves of smell. They originate as specialised olfactory nerve endings (

chemoreceptors

) in the mucous membrane of the roof of the nasal cavity above the superior nasal conchae (

Fig. 8.23

). On each side of the nasal septum nerve fibres pass through the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone to the

olfactory bulb

where interconnections and synapses occur (

Fig. 8.24

). From the bulb, bundles of nerve fibres form the

olfactory tract

, which passes backwards to the olfactory area in the temporal lobe of the cerebral cortex in each hemisphere where the impulses are interpreted and odour perceived (see

Fig. 7.21, p. 150

).

Figure 8.23

The olfactory structures.

Figure 8.24

An enlarged section of the olfactory apparatus in the nose and on the inferior surface of the cerebrum.

Physiology of smell

The human sense of smell is less acute than in other animals. Many animals secrete odorous chemicals called

pheromones

, which play an important part in chemical communication in, for example, territorial behaviour, mating and the bonding of mothers and their newborn. The role of pheromones in human communication is unknown.

All odorous materials give off volatile molecules, which are carried into the nose with inhaled air and even very low concentrations, when dissolved in mucus, stimulate the olfactory chemoreceptors.

The air entering the nose is warmed, and convection currents carry eddies of inspired air to the roof of the nasal cavity. ‘Sniffing’ concentrates volatile molecules in the roof of the nose. This increases the number of olfactory receptors stimulated and thus perception of the smell. The sense of smell may affect the appetite. If the odours are pleasant the appetite may improve and vice versa. When accompanied by the sight of food, an appetising smell increases salivation and stimulates the digestive system (see

Ch. 12

). The sense of smell may create long-lasting memories, especially for distinctive odours, e.g. hospital smells, favourite or least-liked foods.

Inflammation of the nasal mucosa prevents odorous substances from reaching the olfactory area of the nose, causing loss of the sense of smell (

anosmia

). The usual cause is a cold.

Adaptation

When an individual is continuously exposed to an odour, perception of the odour decreases and ceases within a few minutes. This loss of perception affects only that specific odour.

Sense of taste

Learning outcome

After studying this section you should be able to:

describe the physiology of taste.

The sense of taste, or

gustation

, is closely linked to the sense of smell and, like smell, also involves stimulation of chemoreceptors by dissolved chemicals.

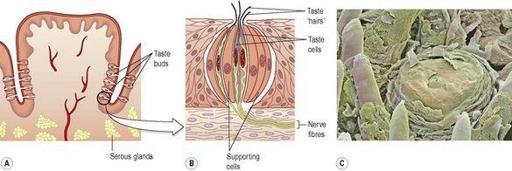

Taste buds contain sensory receptors (chemoreceptors) that are found in the papillae of the tongue and widely distributed in the epithelia of the tongue, soft palate, pharynx and epiglottis. They consist of small sensory nerve endings of the glossopharyngeal, facial and vagus nerves (cranial nerves VII, IX and X). Some of the cells have hair-like cilia on their free border, projecting towards tiny pores in the epithelium (

Fig. 8.25

). The sensory receptors are stimulated by chemicals that enter the pores dissolved in saliva. Nerve impulses are generated and conducted along the glossopharyngeal, facial and vagus nerves before synapsing in the medulla and thalamus. Their final destination is the

taste area

in the parietal lobe of the cerebral cortex where taste is perceived (see

Fig. 7.21, p. 150

).