Rosie's War (2 page)

Authors: Rosemary Say

For us – the therapy generation – such detachment may be understandable but we still want more. We not only want to tell the tale, we also want to explain it.

My mother died before we could finish this account together. She told us all she was able to. This story is the result of her memory and our bullying.

PART ONE

An

Englishwoman

Abroad

JANUARY 1939 – DECEMBER 1940

CHAPTER ONE

Departure for France

L

ate October 1938. A blustery, mid-autumn morning.

I was at a job interview, sitting by the window in a rather shabby, second-floor office of the National Union of Students in central London. I was waiting for some further comments from the lady who was interviewing me, a Miss Coulter. In the meantime, I had quite a good view out of the corner of my eye of the buses crawling down to the Aldwych.

Miss Coulter was elderly and fastidious. She had been silent for quite a time, her lips pursed as she read through some documents piled on her desk. She seemed to shift a little uneasily in her seat.

Had I said something wrong?

I had been trying to sound eager but not desperate. Perhaps I had overdone it and she simply thought that I was either slightly mad, or naïve, and she wasn’t sure how to break the news to me.

I had applied through her organization to go and live in Germany, working as an au pair. Perhaps my choice of location seemed a bit strange, given that we had nearly been at war with that country just a few weeks before. I wasn’t totally ignorant. I had seen the trenches being dug in Hyde Park – a primitive sort of air raid shelter – during the crisis over Czechoslovakia. I had witnessed the panic in London. But, like the majority of ordinary people, I didn’t think war would ever come. Nothing would interfere with my life.

‘Well, Miss Say,’ Miss Coulter said at long last. ‘I don’t think that we’ll be able to help you in your specific request.’ She smiled somewhat patronizingly. ‘I’m sure you appreciate that we can’t really encourage any young person to go to Germany at this particular time.’

She shuffled her papers and looked up at me. I nodded and stared at her rather blankly. I was beginning to feel a bit foolish and embarrassed by the whole procedure. After all, I wasn’t a student, I knew nothing about looking after children and I barely spoke French, let alone any other European language. I felt she knew all this and was politely trying to let me down.

‘What about France?’ she asked after another long silence.

‘I beg your pardon?’

‘Well, we could try to place you in France instead of Germany.’

‘That’s fine with me.’

She looked a bit startled by my ready agreement. I felt like telling her that I would have agreed to go to China if she had told me that it was a good idea. I simply wanted to get away from London and from my family.

Let me give you a little of my background.

I came from a solid, middle-class family. We lived just off Hampstead Heath in North London. My father, a former naval officer, had a comfortable job in the City. He and my mother were Edwardian in outlook, with entirely traditional aspirations for their three children. So, while my brother David had gone up to Cambridge to read theology, I had enrolled on a secretarial course in central London with my older sister Joan.

I was now nineteen years old and had been working for the past year as a secretary at a catering college near to where we lived. It was a large, austere building which reminded me of school, with long, grim corridors where a domestic always seemed to be polishing the floors. It even smelt like school: soap and watery food. I had a very comfortable if rather predictable existence at home. I willingly gave half of my thirty-five shillings a week wages to my mother. I suppose I didn’t really have much need for money: I walked to work where I had food provided, had no desire to save for the future and was paid for at the cinema, the theatre or restaurant by my boyfriend Bobby.

Bobby was part of the problem. He was just too right: ten years older than me, good-looking, our parents firm friends. He was in the process of taking over his father’s auction house in Lisson Grove. It was a business that he would in the future make very successful. On a couple of occasions he had even selected items of furniture for me at the showroom after a night out in town. Our relationship was a settled one and I suppose everyone assumed that we would eventually marry. But it was all very chaste and unexciting.

My great passion was poetry. I took myself very seriously here. I filled notebooks with my own attempts, diligently writing something every day as practice for the future. A rather precious and intellectually arrogant young woman, I would walk the short distance up to Hampstead High Street to hear the major new poets reading their work. I remember listening with rapture one evening as a young W.H. Auden read aloud.

Poetry was even the cause of rows between my mother and me. She rejected poets such as Auden and MacNeice, for example, on the grounds that they were vulgar. Her strait-laced attitude merely strengthened all my feelings of being misunderstood.

I was bored with my safe and predictable life: I wanted out. I longed to dance the light fandango and be silly. It wasn’t that I meant to make trouble for my family, but rather that I didn’t want to go on placating my mother while feeling absolutely mean about how tired I made her. She was a tall, thin woman who always seemed to find life an effort. She had had me at the then advanced age of thirty-four. I had been sent off to boarding school (unlike my siblings) at the age of seven because I was too energetic and noisy. She still seemed to find me too much to cope with.

I had decided earlier in the year that I had to do something different and radical that would break the mould being set for me. But what? It wasn’t until early that autumn, walking over Hampstead Heath one bright, cold afternoon with my schoolfriend Peggy, that I decided exactly what I would do.

‘I’m going to live abroad,’ I declared.

‘Where? How will you live?’

‘Oh, I don’t know. I haven’t got that far yet.’

‘But what will your parents say?’

I looked at Peggy and shrugged my shoulders. The truth was that I had decided on what I was going to do but as yet had no idea of how I would do it. We walked around Highgate Ponds discussing which country I should go to and how I might support myself. All the potential destinations were carefully dissected. After her initial scepticism, Peggy became much more enthusiastic about the whole scheme.

‘My uncle went to Argentina years ago,’ she said. ‘He works for a British railway company there. Perhaps he’d help.’

‘No, it’s too far. I don’t fancy weeks at sea.’

‘Look, if you’re really serious about going somewhere in Europe, why don’t you write to the National Union of Students? My brother has one of their booklets. I’m sure it says they arrange trips for young people on the Continent.’

We went back to Peggy’s house to look at the pamphlet. She was right: the NUS could arrange so-called educational visits for students in Europe, lasting anything from a month to one year.

So, a few days later I settled down to write a long letter to the NUS. I told them that I wanted to go to Germany, giving a lot of spurious reasons for my choice. I remember that one of the more preposterous ones was that I was hoping to be able to hear the famous existentialist philosopher Heidegger lecture at Freiburg University.

My letter must have appeared a bit ridiculous but I can only think now that I felt the need to sound intellectual. After all, this organization was for students, yet I had left school at sixteen and had no hope of going to university.

Why did I choose Germany? Well, I had already ruled out anywhere outside of western Europe. I didn’t want to be too far from my parents after all. But which country then? I had been put off France by my school experience of trying to learn its language. Spain was in the midst of civil war. Germany was perhaps the obvious candidate. I knew a little of the country, having spent a couple of weeks there in my early teens with the Girl Guides. Even in the late 1930s it was easy to focus more on its wonderful cultural achievements of the past than on the actions of its present Nazi government. Yes, our countries might go to war at some point, but that would surely be in the distant future and not during my brief stay there? Anyway, of more importance to me than the choice of country – Germany or France – was the fact that I was going to be living abroad sometime soon.

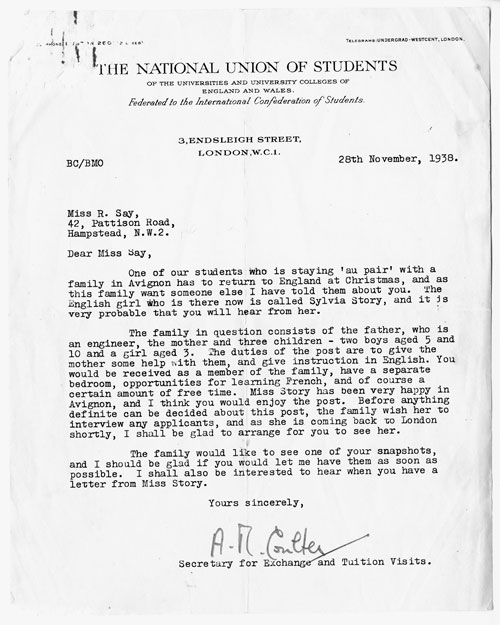

At the end of November a letter arrived from the NUS suggesting a family in Avignon, in the South of France. It appeared that their present au pair, a Miss Sylvia Story, had to return to England at Christmas and they were looking for a replacement. There were three small children.

I showed the letter excitedly to Peggy that evening. She was distinctly underwhelmed.

‘An au pair is a general dogsbody. You’ll be sweeping the floors. You should hold out for a job teaching English at a school.’

‘Well, I think I’ll talk to the present girl when she gets back before I decide anything.’ I was annoyed by her reaction. I wanted her to be enthusiastic. It would help me keep my nerve.

Rosie’s letter from the NUS.

I met Miss Story just before Christmas. We arranged to have coffee one morning at a hotel in the West End of London. She bounded into the lobby laden down with Christmas shopping. She was tall and slim. Her hair was cut into a delightful bob and her clothes were elegant. I couldn’t help wondering whether France would have the same effect on my appearance.

She told me that she had been happy with the family, the Manguins, and described them as gay and delightful. She had been with them for nearly a year but was now returning to England to look after her mother. I did not warm to her. She seemed very bossy and controlling, advising me in no uncertain terms how long I should stay with the Manguins (one year at most) and exactly what work I should be prepared to do. Nevertheless, her obvious possessiveness of the job made me think that the family must be nice. They wanted their replacement to arrive about the second week in January. That settled it for me. I would be abroad early in the New Year.

The night of 9 January 1939 I lay in bed quietly going over all the arrangements in my mind.

I was leaving for Avignon in the morning. At last the family discussions were behind me. My parents had been very cooperative once they had got over their initial shock. Perhaps I should have suspected an element of relief on their part, but if so I was much too taken up with my own plans to worry.

I had some money. Bobby had given me a few French francs. My father, with all sorts of careful warnings about overspending, had presented me with £2 (the equivalent of a little over £80 today). I had carefully locked away the money in one of my new suitcases.

These were the pride of my life. They were made of pale, buff pigskin and were incredibly heavy even when empty. They had my initials stamped on the top in gold. Unlike my school trunk, which bore the name Pat Say, these suitcases proudly proclaimed the owner as Rosemary Say. My father had given me the name Pat after he had returned from sea to be presented with a new baby daughter. ‘Rosemary’s too beautiful a name for her,’ he had declared as he looked at my unprepossessing face. ‘We’ll call her Pat.’ So Pat it was until my suitcases changed all that. My parents had given them to me as a leaving present and I was convinced they were all I needed to complete my new chic French image. The fact that I couldn’t carry even one of them very far didn’t worry me in the least. Travel in those pre-war days always entailed porters and trolleys.

It was a very loaded-down porter’s trolley that carried my suitcases onto the Paris train at Victoria Station the next day. All the family, including Bobby, had come to see me off.

From the photos of the occasion, the scene looks almost Edwardian: my mother tall and elegant in a full-length fur coat; my father, brother and Bobby all in large-lapelled suits and overcoats, wearing Homburg hats and carrying rolled-up umbrellas. My brother David towers above everyone. There’s no avoiding the unmistakeable Say teeth – protruding and prominent – in David, Daddy and me. My mother has a slightly anxious expression on her face. In contrast, I look so excited and happy. I had finally got what I wanted and couldn’t wait to begin. I can hardly turn round to face the camera: I am simply bursting to be gone.