Roosevelt (37 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

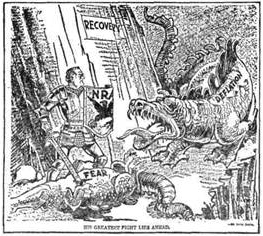

Aug. 1, 1933, Jerry Doyle, Philadelphia

Record

In projecting his charm out to the masses, the President made full

use of the two great media of communication, press and radio. He continued to captivate the reporters in his press conferences with his joshing and fun-making, his swift repartee, his sense of the dramatic, his use of first names and easy geniality. Again and again the press conferences erupted in bursts of laughter.

But Roosevelt’s most important link with the people was the “fireside chat.” Read in cold newspaper print the next day, these talks seemed somewhat stilted and banal. Heard in the parlor, they were fresh, intimate, direct, moving. The radio chats were effective largely because Roosevelt threw himself into the role of a father talking with his great family. He made a conscious effort to visualize the people he was talking to. He forgot the microphone; as he talked, “his head would nod and his hands would move in simple, natural, comfortable gestures,” Miss Perkins noted. “His face would smile and light up as though he were actually sitting on the front porch or in the parlor with them.” And his listeners would nod and smile and laugh with him.

In his first two years in office Roosevelt achieved to a remarkable degree the exalted position of being President of all the people. Could it last? Could he keep a virtually united people behind him?

He could not. Even during his first year there were subdued rumblings of discontent. In 1934 opposition was taking organized form, especially on the right.

The opposition on the right was a mixture of many elements. It was compounded in part of a national reaction to certain elements of the New Deal: the reaction of nineteenth-century individualists to the collectivism of NRA and AAA; of believers in limited government to the leviathan that Roosevelt seemed to be erecting; of champions of thrift to government spending; of opponents of labor organization to politicians who admitted union leaders into high places in the new partnership; of fanatic believers in the sanctity of the gold standard. But there must have been a deeper, more pervasive explanation for the hatred of Roosevelt on the part of people who in many cases had benefited from the New Deal. In the outcries of the anti-Roosevelt sections of business and industry was a sharp, querulous note betraying loss of status, class insecurity, lessened self-esteem. The President was remarkably sensitive to pinpricks from the right, especially from people in his own class. Writing to a Boston banker and Harvard classmate, he went out of his way to mention remarks that he had heard his friend had made, and concluded “because of what I felt to be a very old and real friendship these remarks hurt.” Roosevelt’s ire rose at reports of conversations about him in business circles. “I wish you could have heard the

dinner-party conversations in some of the best houses in Newport,” he wrote to a business friend. He talked caustically to reporters about “prominent gentlemen” dining together in New York and criticizing him.

Ironically enough, Roosevelt made the same complaint against his critics that they directed against him. He said they were doctrinaire, impractical. When his friend James P. Warburg broke with the New Deal because of its monetary policies, Roosevelt wrote Warburg that he had read the latter’s book with great interest. He then urged Warburg to get a secondhand car, put on his oldest clothes, and make a tour of the country. “When you have returned, rewrite ‘The Money Muddle’ and I will guarantee that it will run into many more editions!” The President made much of the fact that conservatives were criticizing the New Deal without offering constructive alternatives.

It was one thing to deal with malcontents off in New York—the “speculators,” as Roosevelt called some of them disdainfully, or “that crowd.” It was something else when opposition developed among his own advisers. His anger rose to white heat when Treasury Adviser O. W. M. Sprague, who he felt had offered no constructive advice toward recovery and who had evidently tried to call protest meetings against New Deal financial policies, resigned late in 1933. Scribbling on some scrap paper, the President wrote Sprague a scorching letter, in which he told him that he would have been dismissed from the government if he had not resigned, and that Sprague’s actions had come close to the border line of disloyalty to the government. The letter was never sent, however. Other advisers resigned: Peek of the AAA, Douglas, Acheson.

Roosevelt seemed almost relieved when the conservative opposition coalesced and organized in the broad light of day. In August 1934 the American Liberty League was chartered, dedicated to “teach the necessity of respect for the rights of persons and property,” the duty of government to protect initiative and enterprise, the right to earn and save and acquire property. Not only were there industrialists like the Du Ponts, automobile manufacturers like William S. Knudsen, oil men like J. Howard Pew, and mail-order house magnates like Sewell L. Avery among its members or spokesmen; there were also illustrious Democratic politicians such as Al Smith, Jouett Shouse, John W. Davis, and Bainbridge Colby. At a press conference the President said amiably that Shouse had been in and had pulled out of his pocket a couple of “Commandments”—the need to protect property and to safeguard profits. What about other commandments? Roosevelt asked. What about loving your neighbor? He quoted a gentleman “with a rather ribald sense

of humor” as saying that the League believed in two things—love God and then forget your neighbor.

Aug. 11, 1934, Rollin Kirby, New York

World-Telegram

“There is no mention made here in these two things,” the President went on, “about the concern of the community, in other words the government, to try to make it possible for people who are willing to work, to find work to do. For people who want to keep themselves from starvation, keep a roof over their heads, lead decent lives, have proper educational standards, those are the concerns of Government, besides these points, and another thing which isn’t mentioned is the protection of the life and liberty of the individual against elements in the community which seek to enrich or advance themselves at the expense of their fellow citizens. They have just as much right to protection by government as anybody else. I don’t believe any further comment is necessary after this, what would you call it—a homily?”

By the fall of 1934 Roosevelt’s break with the Liberty League conservatives seemed irreparable. His own feelings were sharpening. He told Ickes that big business was bent on a deliberate policy of sabotaging the administration. When an ugly general strike broke out in San Francisco, he blamed “hotheaded” young labor leaders, but even more the conservatives who, he said, really wanted the strike. The President’s thoughts must have been far from the grand concert of interests when, referring to his inaugural address, he told reporters, “I would now say that there is a greater thing that America needs to fear, and that is those who seek to instill fear into the American people.” His hopes must have been far from a partnership of all the people when he wrote Garner, after a visit to the Hermitage in November 1934, “The more I learn about old Andy Jackson the more I love him.”

Such was the beginning of the rupture on the right. Much more momentous were the forces of unrest gathering on the left.

THE SOWER, Jan. 4, 1934, Rollin Kirby, New York

World-Telegram

The Grapes of Wrath

S

TUDENTS OF HISTORY HAVE

long observed the tendency of social movements to overflow their channels. Moderate reformers seize power from tired regimes and alter the traditional way of things, and then extremists wrest power from the moderates; a Robespierre succeeds a Danton; a Lenin succeeds a Kerensky. Often it is not actual suffering but the taste of better things that excites people to revolt.

Such was the danger of the early years of the New Deal. The Hoover years had been a period of social statics; the Depression seemed to have frozen people into political as well as economic inertness. Then came the golden words of a new leader, the excitement of bread and circuses, the flush of returning prosperity. Better times led to higher expectations, and higher expectations in turn to discontent as recovery faltered. America had been in a political slack water; now the tide was running strong toward new and dimly seen shores.

Riding this swift-running tide were more radical leaders with new messages for America. They sensed that millions wanted not merely economic uplift but social salvation. They estimated correctly. In a time of vast change and ferment many Americans yearned for leaders who could bring order out of chaos, who could regulate a seemingly hostile world. The New Deal benefits had not reached all these people, nor had even Roosevelt himself. Sharecroppers, old people, hired hands, young jobless college graduates, steel puddlers working three months a year, migratory farm laborers—millions of these were hardly touched by NRA or AAA. Many of them, especially in rural areas, were beyond Roosevelt’s reach; they had no radios to hear his voice, no newspapers to see his face; they belonged to no organized groups.

Politics, like nature, abhors a vacuum, and in the ferment of the early 1930’s these new leaders were busy breeding and capturing discontent. Their main technique was to offer simple, concrete solutions to people bored and confused by the complexities of the New Deal, and to do so by a direct, dramatic pitch. Their appeal

was personal rather than formal, mystical rather than rational. With their mass demonstrations, flags, slogans, and panaceas, they unconsciously followed Hitler’s advice to “burn into the little man’s soul the proud conviction that though a little worm he is nevertheless part of a great dragon.”

The high point in these currents of the great tide came in 1935. It was in this year that Roosevelt came face to face with the men who were turning against the administration and who were hoping to build new citadels of power from the ashes of the New Deal.

On a hot June day early in Roosevelt’s first term a young man with a snub nose, dimpled chin, and wavy hair, strode into the office of the President of the United States. He was Senator Huey P. Long of Louisiana, and he was in a huff. After a few pleasantries he went straight to the point. Huey P. Long, he proclaimed, had swung the nomination to Roosevelt at Chicago. And he had supported the administration’s program. But what had Roosevelt done for him? Nothing. Patronage had gone to the Senator’s enemies in Louisiana, and the President had kept on some of Huey’s old enemies in the administration.

Perched on top of Long’s red hair was a sailor straw hat with a bright-colored band, and there it stayed during the interview, except when the Senator whipped it off and tapped it against the President’s knee to drive home his complaints. This open defiance of presidential amenities upset Farley, who was sitting by, and put McIntyre, who was lurking by the door, into a teeth-clenching rage. But Roosevelt, leaning back in his chair, did not seem to mind a bit. The big smile on his face never left. He answered Long’s arguments pleasantly but firmly. He took no blame for the past, made no promises for the future.