Roosevelt (65 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

When it came to paying for the war and stabilizing the economy, however, the President ran head on into congressional opposition. Most of the legislators seemed to share neither the Jeffersonian concern for equality of sacrifice nor the Hamiltonian doctrine of prudent fiscal management in an economy under stress. In April, Congress terminated the President’s authority to limit salaries, by means of a rider attached to a public-debt measure that he was compelled to sign. Roosevelt bitterly attacked the rider, which was aimed mainly against limitation of salaries (including, incidentally, Roosevelt’s own) to $25,000 a year. “I still believe that the Nation has a common purpose—” he told Congress, “equality of sacrifice in wartime.”

Certainly a large measure of sacrifice was possible. The statistics of the war economy were staggering to a nation raised on Depression scarcities. By mid-1943 war expenditures were reaching the monthly level of seven billion dollars. The national debt would

soon be 150 billion. Since the outbreak of war in September 1939 Americans had saved about seventy billions. A third of this was in currency and checking accounts, a third in redeemable or marketable bonds—“liquid dynamite,” the Treasury’s General Counsel, Randolph Paul, called it. Taxes were running around forty billion a year. The Treasury estimated that income payments to individuals would be over 150 billion for fiscal 1944. Direct personal taxes, at current rates, would skim off about twenty billion, leaving about 130 billion of disposable income. During fiscal 1943 banks had increased their holdings of federal securities by about thirty billion—a key factor in a huge expansion of the total coin, paper money, and checking deposits held by the public.

The President had called for sixteen billion of additional taxes and/or savings in his budget message of 1943. Congressional and public attention had been diverted by a heated dispute in the spring of that year over a scheme of Beardsley Ruml, Treasurer of Macy’s, for a pay-as-you-go income-tax plan that would “forgive” all or part of 1942 taxes. Roosevelt favored pay-as-you-go, but he publicly opposed the Senate version of tax forgiveness on the ground that he could not “acquiesce in the elimination of a whole year’s tax burden on the upper income groups during a war period when I must call for an increase in taxes and savings from the mass of our people.” After the President’s intervention the Senate version was narrowly defeated in the House, which then passed a compromise acceptable to the administration.

With the President’s main goals of big tax boosts still unrealized, Congress seemed exhausted by its forays against salary limitation and for pay-as-you-go. The administration seemed exhausted, too, and divided. Morgenthau was distressed to hear that War Mobilizer Byrnes and Director of Economic Stabilization Vinson were to have a leading role in tax policy. He protested to Roosevelt, who replied that taxes were part of the whole fiscal situation and that the Secretary and Byrnes should deal directly with each other and not through the President. As Byrnes and Vinson continued to negotiate with tax makers on Capitol Hill, Morgenthau seethed over the role of the Kitchen Cabinet. The pattern was perfectly obvious, he told his staff. The people sitting “over there in the left wing of the White House” were trying to run the show, and if they did they could take the blame, too. They were a bunch of ambitious politicians, maneuverers, finaglers. He told his staff to prepare a direct letter to the President as to who was in charge of tax policy. He wanted it straight from the shoulder.

“AW HEN,” the President wrote back. “The weather is hot and I am goin’ off fishing. I decline to be serious even when you see ‘gremlins’ which ain’t there.”

The President talked with Morgenthau soon after, reassured him

as to his primacy in tax policy, and said he wanted twelve billion in new taxes. He advised Morgenthau to put up to Congress various plans that totaled eighteen billion, and let Congress decide on any combination necessary to raise the total. But he would not sign a memorandum to this effect to Byrnes or Vinson. “This is all one big family and you don’t do things that way in a family.”

This led to a sharp family quarrel early in September when Morgenthau met with the President and Byrnes. Byrnes was pretty bitter and hot, Paul reported; the President tried to stop him a couple of times but Byrnes slugged right on. Who was in charge of tax policy? “I am the boss,” Roosevelt said. “…We must agree….Then when we agree, I expect you fellows to go in and do the work just like soldiers.” Byrnes said he would not work for the bill unless he had a voice in it. He got along with people all right—he got along with Knox and Stimson—but he couldn’t get along with Morgenthau. Roosevelt was now aroused. Pounding the table, he insisted again, “I am the boss. I am the one who gets the rap if we get licked in Congress.…I am the boss, I am giving the orders.”

Despite the raw tempers, Morgenthau and his staff plugged away at new tax proposals and Social Security expansion. For a time the Treasury toyed with the idea, radical in the United States, of including medical insurance under Social Security, but Roosevelt was wary. The people were not ready, he felt. “We can’t go up against the State Medical Societies,” Roosevelt reassured Senator George, “we just can’t do it.” Morgenthau concentrated on a tough tax program. Early in October 1943 the Secretary, with the President’s blessing, presented the administration’s new proposals to Congress. They called for 10.5 billion dollars of additional taxes; four billion of estate and gift taxes, corporate taxes, and excises. Morgenthau also proposed repeal of the victory tax, which would take nine million low-income taxpayers off the tax rolls.

The reaction of most congressional leaders ranged from cool to hostile. The legislators seemed far removed from the new memorial in the Tidal Basin and the egalitarian figure who occupied it.

During late 1942 and early 1943 British leaders were concerned less with long-run peace planning than with immediate postwar settlements and arrangements. Anthony Eden had taken the lead in exploring such questions. In February 1943 Churchill suggested to Roosevelt that the Foreign Secretary talk with him on the subject. “Delighted to have him come—the sooner the better,” Roosevelt replied. Hull was vacationing in Florida at the time; when Welles told him that the President and he felt that they could carry on

the conversations with Eden and hence Hull need not interrupt his vacation, the Secretary took the next train to Washington.

He hardly needed to worry. Roosevelt was even more cautious in approaching immediate postwar arrangements than in long-term planning for peace. The aftermath of Versailles was a constant, nagging reminder to him—a factor as crucial in his thinking as Passchendaele and the Somme were in Churchill’s military planning. Roosevelt still preferred to put off making postwar political plans, but increasingly, it seemed, key wartime military decisions had a sharp political edge and crucial postwar implication. So Roosevelt decided to go ahead with Eden, but quietly and tentatively.

Hour after hour Roosevelt and Eden talked together, sometimes with Hull and Halifax, sometimes only with Hopkins, sometimes with a larger company, but never with the military. Roosevelt was still keeping separate the discussion of military and political plans. With Eden he roamed around the globe, but the starting and ending place always seemed to be Russia. What would Stalin want after the war? Eden was sure he planned to absorb the Baltic states into the Soviet Union. This would antagonize American public opinion, Roosevelt felt; since the Russians would be in the Baltic countries when Germany fell, they could not be forced out. He wondered if Stalin would accept a plebiscite, even if a fake one. Eden was doubtful. Perhaps then, Roosevelt said, yielding on this score could be used as a bargaining instrument to get other concessions from the Russians.

The two men agreed that Russia would insist on its prewar boundaries with Finland, and that this was reasonable; they feared that Stalin would demand Hangö, too. But Finland would clearly be a postwar problem, and Poland even more so. The President and the Foreign Secretary agreed that Poland should have East Prussia; Roosevelt added that the Prussians would have to be moved out of the area, just as the Greeks were moved out of Turkey after World War I. This was a harsh method, he granted, but the only way to maintain peace; besides, the Prussians could not be trusted.

The roaming went on.

Serbia:

Roosevelt had long believed that Croats and Serbs had nothing in common and should be separated.

Austria and Hungary:

these should be established as independent states.

Turkey and Greece:

no problem from a geographical point of view.

Belgium:

the President proposed, while Eden listened skeptically, that the Walloon parts of Belgium be combined with Luxembourg, Alsace-Lorraine, and a part of northern France, to make up a new state of “Wallonia.”

Germany:

Roosevelt wanted to avoid the Versailles error of dealing with the defeated enemy; he preferred encouraging differences and ambitions that would

spring up in Germany and lead toward separatism on the part of major regions. In any event Germany must be divided into several states in order to weaken it. Roosevelt agreed with Hopkins that it was to be hoped that Anglo-American troops would be in Germany in strength when Hitler quit and could prevent anarchy or Communism, but it would be well to work out with the Russians a plan as to just where the armies should stand, especially in the event Germany collapsed before the Americans and British got deeply into France. Hull favored a simpler approach. He hoped that Hitler and his gang would not be granted a “long-winded public trial” but would be quickly shot out of hand.

The major long-run issue was, of course, postwar world organization. Roosevelt and Welles were still emphatic that the United States would not join any independent body such as a European council, but, rather, that all the United Nations should be members of one world-wide body to recommend policies, while representatives of the Big Four and of six or eight regional groupings could make up an advisory council. Real power—especially policing power—should be exercised by the Big Four. Eden was doubtful that China, with its historic instability, could be part of a Big Four; China might well have to go through revolution after the war, he thought. There was some discussion of Asia after the war, but most of it inconclusive. Hopkins guessed that the British were going to be “pretty sticky” about their former possessions in the Far East.

Roosevelt told Churchill and others that he and Eden agreed on 95 per cent of “everything from Ruthenia to the production of peanuts!” Over oysters at the Carlton, Eden told Hopkins he was surprised at the President’s intimate knowledge of geographical boundaries. He enjoyed watching the play of Roosevelt’s mind, but he had misgivings. There was something almost alarming in the cheerful fecklessness with which the President seemed to dispose of the fate of whole countries. He was like a conjuror, Eden felt, deftly juggling with balls of dynamite whose nature he did not understand.

No conjuring could dispel the lowering clouds over the discussions. What was Stalin’s postwar design? Did he plan to dominate eastern and central Europe, establish a belt of satellites, foment revolution, even overrun the whole Continent? Or would he work for peace with the West, in the spirit of the United Nations? Roosevelt was not uninformed, naïve , or incredulous in facing these questions. He was prepared to bargain and demand, resist and compromise, like any good horse trader, in dealing with Moscow’s demands.

What the President did not seem to grasp in its fullest implications, however, was the relation between Soviet options and the immediate policies that the West was following. He and Eden discussed Soviet plans somewhat abstractly, as though Moscow had already set a definite course, whatever it might be. The two did see the possibility that the Kremlin might be caught between two sets of policies, benign and aggressive; thus Stalin, at the height of his disappointment with the West over the second front, dissolved the Comintern as a gesture of good will toward his allies. But Roosevelt did not fully recognize the implications of immediate military planning for long-run strategic questions.

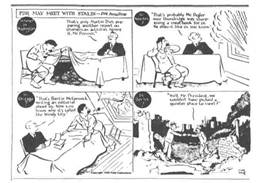

April 5, 1943, Carl Rose,

PM,

reprinted by courtesy of Field Enterprises, Inc.

The burning issue was still the cross-channel invasion. The timing of the invasion had been left so vague at Casablanca that Roosevelt and Churchill agreed at the end of April that they must meet to discuss this and other pressing questions. At this point, though, the President was more interested in seeing Stalin than Churchill. Aware that relations with Moscow had fallen to a new low after postponement of the cross-channel plan and the suspension of northern convoying, Roosevelt reasoned that by talking face to face with Stalin he could take a direct measure of the man, establish a personal rapport, and reassure the Kremlin on Washington’s plans and motives. He thought he could satisfy “Uncle Joe” as to cross-channel and other harsh issues. They were both practical men, after all. Certainly he could do better than Churchill.

Roosevelt was scornful of press reports from London that Churchill would be the good broker between Russia and the United States. If anyone was to be a broker, it would be he.