Roosevelt (6 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

Every ounce of the Cabinet’s talent and militance was needed in the fall of 1940. It was clear that Britain faced a crisis of shipping, supply, and money. There were rumors of mighty strategic decisions being made in enemy capitals. Interventionists were demanding action; the President had a mandate for all aid to Britain short of war—why didn’t he deliver? But nothing seemed to happen. When Lord Lothian, the British Ambassador, returned from London late in November with a warning that his nation was nearing the end of its financial resources, Roosevelt told him that London must liquidate its investments in the New World before asking for money.

While official Washington waited for marching orders, the President took a four-day cruise down the Potomac to catch up on his sleep. Then he upset press predictions by making no changes in his Cabinet, tried unsuccessfully to persuade the aged General John J. Pershing to serve as ambassador to Vichy France, asked Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish to find out if the Cherable Islands, which he had once told reporters he would visit, could be found in poetry or fiction (they could not), and called for an annual Art Week under White House sponsorship. The President made it clear that he would not ask for repeal or modification of the Neutrality Act, which forbade loans to belligerents, or of the Johnson Act, which forbade loans to countries that had defaulted on their World War I debts.

At a press conference, the President fended off reporters who were looking for big postelection decisions on the war. It was all very good-natured. Asked by a reporter whether his economy ban on civilian highways included parking shoulders for defense highways, the President could not resist the opening.

“Parking

shoulders

?”

“Yes, widening out on the edge, supposedly to let the civilians park as the military go by.”

“You don’t mean necking places?”

The reporters roared, but they got precious little news. The administration seemed to be drifting. Then on December 3 the President boarded the cruiser

Tuscaloosa

for a ten-day cruise through the Caribbean. Besides his office staff he took only Harry Hopkins.

While Roosevelt fished, watched movies, entertained British colonial officials—including the Duke and Duchess of Windsor—and looked over naval bases, Cabinet officers back in Washington struggled with the dire problem of aid to Britain. Production officials agreed that American industry could produce enough for both countries, and army chiefs were happy to supply British as well as American needs, for this would require an enormous expansion of defense production facilities, but what about the financing? The

British in Washington contended that they could not possibly pay for such a huge program. Morgenthau asked Jesse Jones, head of the Reconstruction Finance Corporation, if he could legally use its funds to build defense plants. For the War Department, yes, said Jones, but not for the British. Stimson argued that the administration must no longer temporize, but present the whole issue to Congress, and the others agreed. But this seemed a counsel of despair; everyone could imagine the explosion on Capitol Hill if the issues were clearly drawn. And would the President risk a legislative defeat of this magnitude?

A thousand miles south, Navy seaplanes were bringing the President daily reports on these anxious searchings. Then, as the

Tuscaloosa

sat off Antigua in the bright sun, a seaplane arrived with Churchill’s fateful postelection letter. No one remembered later that Roosevelt seemed especially moved by it. “I didn’t know for quite a while what he was thinking about, if anything,” Hopkins said later. “But then—I began to get the idea that he was refueling, the way he so often does when he seems to be resting and carefree. So I didn’t ask him any questions. Then, one evening, he suddenly came out with it—the whole program. He didn’t seem to have any clear idea how it could be done legally. But there wasn’t a doubt in his mind that he’d find a way to do it.”

The “whole program” was Lend-Lease—the simple notion that the United States could send Britain munitions without charge and be repaid not in dollars, but in kind, after the war was over.

This was no rabbit pulled out of a presidential hat. Churchill’s letter had acted merely as a catalyst. A British shipbuilding mission had recently arrived in Washington to contract for ships to be built in the United States. For weeks, perhaps months, the President had been thinking of building cargo ships and leasing them to Britain for the duration. Why not extend the scheme to guns and other munitions? This apparently simple extension, however, represented a vast expansion and shift in the formula. There was no way that Britain could return thousands of planes and tanks after the war; there was no way that Americans could use them if it did. Maritime Commission officials had opposed even the leasing of ships, on the ground that the United States would not need a large fleet after the war and would be stuck with a lot of useless vessels. If this was true of ships, it was doubly true of tanks and guns. But so adroitly and imaginatively did Roosevelt handle the matter that for a long time its critics made every objection except the crucial one.

Armed with his formula, restored and buoyant after his trip, the President returned to Washington on December 16 and plunged into a series of conferences with his anxious advisers. The next two weeks were one of the most decisive periods in Roosevelt’s

presidency. His foxlike evasions were put aside; now he took the lion’s role.

In one of the surprises he enjoyed engineering he sprang his plan at a press conference. Though he disclaimed at the start that there was “any particular news,” the reporters could tell from his airs—the uptilted cigarette holder, rolled eyes, puffing cheeks, bantering tone—that something was up. He began casually. He had been reading a good deal of nonsense, he said, about finances. The fact was that “in all history no major war has ever been won or lost through lack of money.” He scornfully recalled meeting his banking and broker friends on the Bar Harbor Express at the outset of World War I and their telling him that the war could not last six months because the bankers would stop it. Some “narrow-minded people” were talking now about repealing the Neutrality Act and the Johnson Act and about lending money to Britain. That was “banal.” Others were talking about sending arms, planes, and guns to Britain as a gift. That was banal, too. The best idea—talking selfishly, from the American point of view, “nothing else”—was to build production facilities and then “either lease or sell the materials, subject to mortgage,” to the people on the other side.

“Now what I am trying to do is to eliminate the dollar sign. That is something brand new in the thoughts of practically everybody in this room, I think—get rid of the silly, foolish old dollar sign.

“Well, let me give you an illustration: Suppose my neighbor’s home catches on fire, and I have a length of garden hose four or five hundred feet away. If he can take my garden hose and connect it up with his hydrant, I may help him to put out his fire. Now what do I do? I don’t say to him before that operation, ‘Neighbor, my garden hose, cost me $15; you have to pay me $15 for it.’ What is the transaction that goes on? I don’t want $15—I want my garden hose back after the fire is over. All right. If it goes through the fire all right, intact, without any damage to it, he gives it back to me and thanks me very much for the use of it.” If his neighbor smashed it up he could simply replace it.

The reporters pressed him. Would this mean convoying? No. The Neutrality Act would not need to be amended? Right! Was congressional approval necessary? Yes. Would such steps bring a greater danger of getting into war than the existing situation? No, of course not. Nobody asked the President what use repayment “in kind” would be after the war, and hence why his plan was not an outright gift of munitions.

By now Berlin could no longer remain quiet. Fearing that Roosevelt would turn over to Britain 70,000 tons of German shipping in American ports, and that the United States Navy might begin to escort cargo ships, a Wilhelmstrasse spokesman warned that Roosevelt’s policy of “pinpricks, challenges, insults, and moral aggression” had become “insupportable.”

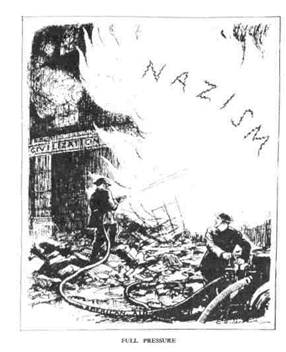

January 8, 1941, Ernest H. Shepard,© Punch, London

But the climax of Roosevelt’s year-end effort was yet to come. On the evening of December 29 he was wheeled into the diplomatic reception room and seated in front of a plain desk covered with microphones indicating their networks: NBC, CBS, MBS. Around him in the hot little room was jammed a small and mixed group: Cordell Hull and other Cabinet members, Sara Roosevelt, Clark Gable and his wife, Carole Lombard. The President, wearing pince-nez and a bow tie, seemed grave but relaxed.

“This is not a fireside chat on war,” he began in his smooth, resonant voice. “It is a talk on national security; because the nub of the whole purpose of your President is to keep you now, and your children later, and your grandchildren much later, out of a last-ditch war for the preservation of American independence and all the things that American independence means to you and to me and to ours….

“Never before since Jamestown and Plymouth Rock has our American civilization been in such danger as now….

“The Nazi masters of Germany have made it clear that they intend not only to dominate all life and thought in their own

country, but also to enslave the whole of Europe, and then to use the resources of Europe to dominate the rest of the world.”

Roosevelt quoted Hitler’s statement of three weeks earlier: “ ‘There are two worlds that stand opposed to each other.’ ”

“In other words, the Axis not only admits but

proclaims

that there can be no ultimate peace between their philosophy of government and our philosophy of government.”

The President then reviewed the history of Nazi aggression and the Nazis’ attempts to justify it by “various pious frauds.” He charged that Americans in high places were “unwittingly, in most cases,” aiding foreign agents. “The experience of the past two years has proven beyond doubt that no nation can appease the Nazis. No man can tame a tiger into a kitten by stroking it…. The American appeasers…tell you that the Axis powers are going to win anyway; that all this bloodshed in the world could be saved; that the United States might just as well throw its influence into the scale of a dictated peace, and get the best out of it that we can.

“They call it a ‘negotiated peace.’ Nonsense! Is it a negotiated peace if a gang of outlaws surrounds your community and on threat of extermination makes you pay tribute to save your own skins?”

Then the President renewed his pledge to keep out of war. “Thinking in terms of today and tomorrow, I make the direct statement to the American people that there is far less chance of the United States getting into war, if we do all we can now to support the nations defending themselves against attack by the Axis than if we acquiesce in their defeat, submit tamely to an Axis victory, and wait our turn to be the object of attack in another war later on.

“If we are to be completely honest with ourselves, we must admit that there is risk in any course we may take. But I deeply believe that the great majority of our people agree that the course that I advocate involves the least risk now and the greatest hope for world peace in the future….” The government did not intend to send an American expeditionary force outside its borders. “You can, therefore, nail any talk about sending armies to Europe as deliberate untruth.”

“Our national policy is not directed toward war. Its sole purpose is to keep war away from our country and our people.”

He appealed to the nation to put every ounce of its effort into producing munitions swiftly and without stint. “We must be the great arsenal of democracy. For us this is an emergency as serious as war itself….

“There will be no ‘bottlenecks’ in our determination to aid Great Britain. No dictator, no combination of dictators, will weaken that determination by threats of how they will construe that determination….”

The speech was sending a thrill of hope across the anti-Nazi world. Londoners, crouching by their radios, listened avidly to the now reedy, now vibrant voice coming across the Atlantic. On this night the Nazis were fire-bombing London in the heaviest attack the city had known. Far away in Tokyo, Grew felt that the speech marked a turning point in the war; he read it so often he came to know it almost by heart. Telegrams began streaming into the White House; later, secretaries reported that the letters and wires had run a hundred to one in support.

The speech had the bracing tonic of conviction and faith. “I believe that the Axis powers are not going to win this war,” the President said. “I base that belief on the latest and best information.” Actually, Roosevelt’s only information was his faith that Lend-Lease would pass Congress and make an Axis victory impossible.

He concluded with a plea for the mightiest production effort in American history: “As President of the United States I call for that national effort. I call for it in the name of this nation which we love and honor and which we are privileged and proud to serve. I call upon our people with absolute confidence that our common cause will greatly succeed.”