Roosevelt (108 page)

Authors: James MacGregor Burns

The train threaded its way along the curving tracks on the bank of the Hudson, passing the towering palisades across the river—High Tor, Sugar Loaf, Storm King. At Garrison, opposite West Point, men removed their hats just as they had done at Garrison’s Landing eighty years before. Then Cold Spring, Beacon, Poughkeepsie, on the bank of the Hudson, the river of American politics.

Around the world men who had known Roosevelt were struggling to phrase their eulogies. Churchill was preparing a tribute for Parliament, but he would say nothing more cogently than his Teheran toast to Roosevelt as a leader who had “guided his country along the tumultuous stream of party friction and internal politics amidst the violent freedom of democracy.” Ivan Maisky would remember him as a statesman of very great caliber, with an acute mind, a wide sweep in action, vast energy, but in the end essentially bourgeois, flesh of the flesh of the American ruling class. John Buchan felt that he had never met a man more fecund in ideas; Robert Sherwood found him spiritually the healthiest man he had ever known; Henry Stimson called him an ideal war commander in chief, the greatest war President the nation had ever had. Young Congressman Lyndon Johnson, grieving over the news of the death of his friend, said Roosevelt was the only person he had ever known who was never afraid. “God, how he could take it for us all!”

A second-rate intellect, Oliver Wendell Holmes had called him, but a first-rate temperament. To examine closely single aspects of Roosevelt’s character—as thinker, as organizer, as manipulator, as strategist, as idealist—is to see failings and deficiencies interwoven with the huge capacities. But to stand back and look at the man as a whole, against the backdrop of his people and his times, is to see the lineaments of greatness—courage, joyousness, responsiveness, vitality, faith. A democrat in manner and conviction, he was yet

a member of that small aristocracy once described by E. M. Forster—sensitive but not weak, considerate but not fussy, plucky in his power to endure, capable of laughing and of taking a joke. He was the true happy warrior.

“All that is within me cries out to go back to my home on the Hudson River,” Roosevelt had said nine months before. The train, still hugging the riverbank, crossed from Poughkeepsie into Hyde Park. It was Sunday, April 15, 1945, a clear day, the sky a deep blue. Tiny waves were breaking against the river shore where the train slowed and switched off into a siding below the bluff on which the mansion stood. Cannon sounded twenty-one times as the coffin was moved from the train to a caisson drawn by six brown horses. Standing behind was a seventh horse, hooded, stirrups reversed, sword and boots turned upside down hanging from the left stirrup—symbolic of a lost warrior.

Following the beat of muffled drums the little procession toiled up the steep, winding, graveled road, past a small stream running full and fast, past the ice pond, with its surface a smoky jade under the overhanging hemlocks, past the budding apple trees and the lilacs and the open field, and emerged onto the height. In back of the house, standing in the rose garden framed by the hemlock hedge, was a large assembly: President Truman and his Cabinet and officialdom of the old administration and family and friends and retainers, a phalanx of six hundred West Point cadets standing rigidly at attention in their gray uniforms and white crossed belts. Behind the coffin, borne now by eight servicemen, Eleanor Roosevelt and her daughter, Anna, and her son Elliott moved into the rose garden.

The aged rector of St. James Episcopal Church of Hyde Park prayed—“…earth to earth, ashes to ashes, dust to dust.” Raising his hand as the servicemen lowered the body slowly into the grave, he intoned:

“Now the laborer’s task is o’er,

Now the battle day is past,

Now upon the farther shore

Lands the voyager at last….”

A breeze off the Hudson ruffled the trees above. Cadets fired three volleys. A bugler played the haunting notes of Taps. The soldier was home.

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

Hyde Park in the piping days of peace. Franklin D. Roosevelt receiving a medal on his 25th anniversary as an Odd Fellow in Hyde Park Lodge 203, September 16, 1938

United Press International

President Roosevelt in Washington, Lincoln’s Birthday, 1940

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

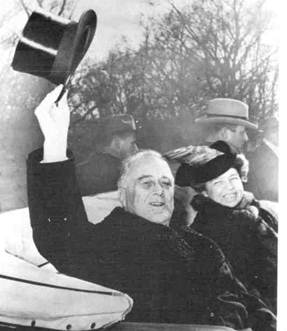

Returning to the White House with Mrs. Roosevelt after the third inaugural, January 20, 1941

Franklin D. Roosevelt Library

Roosevelt with Winston Churchill at the Atlantic Charter conference, Argentia, Newfoundland, August 9-12, 1941. General George C. Marshall stands in the middle above.

The President reading the joint resolution by both houses of Congress declaring that a state of war exists with Germany and Italy, December 11, 1941

United Press International

Photo by Heinrich Hoffmann, © 2968 by Christian Wegner Verlag

Reprinted by permission of Harcourt, Brace if World, Inc.

Hitler and Mussolini conferring in 1941

Brown Brothers

Emperor Hirohito of Japan

Joint press conference with Winston Churchill, Washington, D.C., December 23, 1941

United Press International