Rome: An Empire's Story (40 page)

Identity politics looks very different in discussions of modern imperialisms. There the focus is not on the emergence of vast imperial identities, but rather on how imperial regimes have shaped local experiences; on the emergence of newly self-conscious peoples and nations; on diasporas and displacements; and on how the experience of migration has impacted on the lives of countless individuals. Cosmopolitanism, cultural hybridity, and the persistence of economic and cultural domination after the end of formal empire are central topics in post-colonial studies. Enormous differences clearly existed between the long-lasting, but fundamentally weak, empires of antiquity, and the short-lived but phenomenally powerful ones of the last few hundred years. Ancient imperialisms never effected population transfers on the scale either of the transport of Africans to the New World as slaves; or the establishment of populations of south Asian origin in Africa, Europe, and North America; or the spread of communities of east Asian origin around the Pacific; let alone the colonization of much of the world’s temperate zones by people of European origin. Modern empires established vast inequalities of wealth that persist today. Because of their impact on public health, and because they exported cash-cropping and industrialization into their peripheries, they set in train enormous changes in the global environment. Cosmopolitanism in the modern world is linked to the creation of huge cities, in both the developed and underdeveloped worlds. Any comparison with antiquity has to bear those differences in mind.

Post-colonial approaches to classical antiquity and an interest in processes of globalization processes and localization in the Roman world are relatively new, but a few recent studies indicate their potential.

17

Long before Rome expanded, both the Mediterranean world and its continental hinterlands experienced population movements of various kinds.

18

Nevertheless, Roman imperialism presided over what were probably unprecedented levels of human mobility in the ancient Mediterranean world. The slave trade; the recruitment, redeployment, and resettlement of soldiers; and the growth of cities all played a part. We should probably imagine net flows of humans into the core provinces, especially into the most urbanized regions, since ancient cities certainly had higher death rates than birth rates, and relied on

immigration to sustain their populations. Roman authorities also occasionally moved tribal populations across frontiers. Missionaries, pilgrims, traders, travelling scholars, and craftsmen all travelled back and forth across the empire, many at least intending to return home.

19

When they did not, their tombstones provide precious information about their travels, while a range of techniques for analysing skeletal material provide objective evidence.

20

Alongside this can be set the legal and documentary evidence for efforts to respond to human mobility, and to control it: Greek cities had already developed regulation for

metoikoi

(resident aliens) and western ones began to impose financial obligations on wealthy

incolae

(inhabitants of a community whose formally registered place of origin was elsewhere).

21

Diasporas of Jews and Syrians and Greeks are reasonably well attested during the empire.

22

Very often it is the spread of the worship of particular gods that provides the best evidence for diaspora communities across the empire.

23

Atargatis, known as Dea Syria, the Syrian goddess, eventually attracted other worshippers, but it looks as if the founders of her temples in the Aegean and in Italy were actual migrants. Synagogues are known throughout the Roman east, and in some parts of the west as well. The fact that cult centres were established in new locations suggests not only semi-permanent populations, but also groups who maintained contacts with fellow immigrants from the same areas. All major Roman cities contained minorities within them, and where there is abundant epigraphic evidence as in the Vesuvian cities, Ostia, and some North African ports, these communities are highly visible.

But there is little sign of any positive value being placed on hybridity or multiculturalism by the host societies. Although the rich spent a good deal acquiring exotic foreign raw materials, from Indian Ocean spices to silk, they were not interested in consuming alien cuisine, or dressing in new ways influenced by foreign styles. Jews and Isis worshippers were both hounded out of Rome in the late Republic. The upwardly mobile took care to lose their regional accents. Only Greek orators could make capital out of their exotic origins: Lucian stressed his ‘Assyrian’ identity, and Favorinus of Arles stated that one of the paradoxes of his life was that although he was a Gaul, he could ‘play the Greek’. But what they were stressing was the cultural distance they had travelled. Septimius Severus allegedly would not let his sister come to Rome even when he was emperor, because he was embarrassed by her African speech.

Being part of an empire also had more subtle effects on the identities claimed by different peoples in the empire. Theorists of globalization today

point out that increased connectivity has often had the effect of making a group more conscious of its distinctive location within the whole. It has been suggested that both Greeks and Jews came to formulate their distinctive identities in new ways that responded to the wider imperial world in which they lived.

24

Some aspects of Jewish life, from the use of Greek to a form of worship based on scriptures rather than the rituals of the Temple in Jerusalem, were more portable and so easier to replicate in a Greek or Roman city. Greek education too was more transferable than rituals based on ancestral shrines. Isis worshippers could use hieroglyphs in their rituals, and even imported Nile water, but they could not orient cult on the flooding of the river. Many cults came to resemble each other in their outward-looking faces, while remaining (or even becoming more) distinctive in terms of what worshippers did or knew on the inside. Diasporic populations were not the only ones to find new identities in the empire. Local communities in east and west developed parallel myth-histories, peopled with Trojan and Greek founding fathers and a range of similar tropes, the local princess who marries the refugee prince, the oracle that points to the spot where the city should be founded. This myth-making was an ancient tradition, but it flourished in all parts of the Roman world.

25

Further Reading

Almost no topic in Roman history has generated as much recent research as the subject of this chapter, although there has been some confusion between attempts to examine the broad social and economic consequences of Roman rule; studies of collective identities as consciously experienced phenomena, as expressed in texts, monuments, and material culture; and investigations of the means by which loyalty and solidarity were generated among the emperors’ subjects. Those issues are clearly linked, but they are not the same.

Studies of the impact of Roman rule vary considerably, especially in how they treat cultural phenomena. Examples include Martin Millett’s

Romanization of Britain

(Cambridge, 1990), Nico Roymans’s

Tribal Societies in Northern Gaul

(Amsterdam, 1990), Susan Alcock’s

Graecia capta

(Cambridge, 1993), David Mattingly’s

An Imperial Possession

(London, 2006), Andrew Wallace-Hadrill’s

Roman Cultural Revolution

(Cambridge, 2008) and my own

Becoming Roman

(Cambridge, 1998); they offer a selection of approaches, all employing archaeological data, generally in combination with other evidence. So too do two collections, Tom Blagg and Martin Millett’s

Early Roman Empire in the West

(Oxford, 2000) and Susan Alcock’s

Early Roman Empire in the East

(Oxford, 1997). It would be easy to add to this list.

Conscious expressions of Roman identity are the subject of Emma Dench’s

Romulus’ Asylum

(Oxford, 2005) while Simon Swain’s

Hellenism and Empire

(Oxford, 1996) and Simon Goldhill’s

Being Greek under Rome

(Cambridge, 2001) investigate the identity politics of the empire’s best-documented subject people. Seth Schwartz’s

Imperialism and Jewish Society

(Princeton, 2001) asks some of the same questions about the second best-known case. Fergus Millar’s

Roman Near East

(Cambridge, Mass., 1993) opens up a vast field of study, one mostly known from inscriptions written in a bewildering variety of languages. By far the most thoughtful examination so far of how cultural identity, political power, law, and social solidarity were connected during the early empire is Clifford Ando’s

Imperial Ideology and Provincial Loyalty in the Roman Empire

(Berkeley, 2000).

Most recently attention has focused on how particular groups within the empire developed common identities often based on social memory. Three recent collections give an idea of the state of the question: Ton Derks and Nico Roymans’s

Ethnic Constructs in Antiquity

(Amsterdam, 2009), Tim Whitmarsh’s

Local Knowledge and Microidentities in the Imperial Greek World

(Cambridge, 2010), and Erich Gruen’s

Cultural Identities in the Ancient Mediterranean

(Los Angeles, 2011), which includes much else besides.

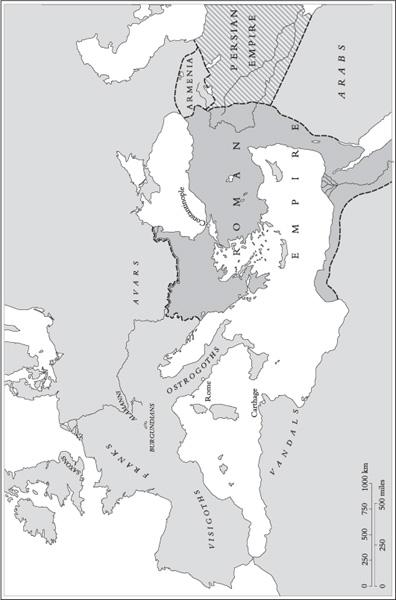

Map 6.

The empire in the year 500

AD

KEY DATES IN CHAPTER XV

AD | Reign of Diocletian |

AD | The Great Persecution |

AD | Reign of Constantine |

AD | Constantine’s Edict of Toleration |

AD | Council of Nicaea |

AD | Reign of Julian |

AD | Valens allows parties of Goths to cross the Danube, beginning the events leading to the defeat of the eastern Roman army at Adrianople |

AD | On the death of Theodosius the empire is ruled by Honorius in the west and Arcadius in the east, both of them minors |

AD | Progressive conquest of Iberian peninsula by Visigoths |

AD | Rome sacked by the Goths |

AD | Vandals invade Africa, capturing Carthage in ad 439 |

AD | Compilation of |

AD | The Huns, led by Attila, ravage the Balkans, Gaul, and Italy |

AD | Rome sacked by the Vandals |

AD | Last western emperor deposed by Odoacer the Ostrogoth |

XV

RECOVERY AND COLLAPSE

When Polybius of Megalopolis decided to make a record of the most significant events of his own day, he thought it was appropriate to begin by demonstrating on the basis of the facts, that the Romans did not win a great empire in the six hundred years following the foundation of the city, even though they were regularly at war with their neighbours for all this period. On the contrary, that occurred only after they had captured a part of Italy and then lost it once again after the invasion of Hannibal, the defeat at Cannae, and only after they had actually seen from their walls the enemy threatening. Only then did they begin to be so favoured by fortune, that in less than fifty-three years, they took control not only of all Italy but all Africa as well. The Iberians of the west submitted to them. Setting out on an even greater project they crossed the Adriatic, conquered the Greeks, and dissolved the empire of Macedon, capturing alive their king and carrying him off to Rome as a prisoner. Nobody could attribute this success to human might alone. The explanation must lie in the immutable plan of the Fates, the influence of the planets, or the will of God that favours all human enterprises so long as they are just. For these things establish a pattern of causation that leads future events to come out in just such a way, that shows just how right they are who believe that human affairs are subject to some kind of Divine Providence. So that when their energy is aroused, they flourish; but when they become displeasing to the gods, their affairs decline to a state like that which now exists. The truth of this proposition will be demonstrated by the events I will now relate.