Rogue Powers (18 page)

The scientific establishment of Bandwidth couldn't do anything about vaporized stellarists, but it could correlate results, and the computers were there for number crunching problems where the number of variables was itself a large but variable number. The field astronomers looked down on their ground-based colleagues, the theoretical astronomers, and harbored a suspicion that they were little more than computer programmers and librarians—but then, scientists had never really understood how much they relied on those two professions. Dr. Raoul Morelles liked to think of himself as a spider at the center of its web, all the threads leading back to center. Bandwidth and Earth, there were the two places the data came, and maybe Earth has computers as good—but try getting at them! Bandwidth was the place to work. Interesting problems cropped up all the time. Morelles didn't look like a spider— closer to a praying mantis. Very tall and thin, with a shock of white hair that stood straight up from being endlessly shoved out of his eyes, large, serious eyes, and long arms and legs, with delicate, almost frail-looking hands. He seemed always to be deliberately holding himself very still, as if he was concentrating on something that might vanish if he looked away. His clothes were worn and spare, the old workshirt and the khaki trousers that he found most comfortable, a pair of slightly shabby slippers.

When he answered the doorbell to find two slightly embarrassed young men, he had a hunch that he was about to find himself in the middle of a very interesting problem indeed. They didn't seem the usual sort of visitor. They weren't grad students trying to butter him up in his capacity as a professor, anyway. No naval officers at the school.

Mostly out of curiosity, he let them in. They got the introductions out of the way, Morelles ordered the kitchen to make coffee and deliver it to his study, and they sat down to talk.

"It's this way, Dr. Morelles," Metcalf began. "As you might know, there's a lot of effort being put into finding the planet Capital, where the Guardians come from."

"I don't follow the war news much, but I have heard something about it, yes. Do go on."

"Well, George here is from Capital, but he's working with us. He and I were talking tonight, and it struck me that we've been going about it all wrong. The Intelligence teams wave star charts and ask about spectral types and so on, but it doesn't do any good. The prisoners they're interrogating don't

know

any of that stuff I was talking with George, and he got to describing the night sky, the way the people see it and understand it, and their assumptions about the sky and how it worked. What I want is to work backwards. I want to figure out what must be in the sky for it to look and move the way it does. Like the ancients figuring out the Earth is in orbit by seeing the Sun rise. I want to find the pattern to fit the facts, instead of just casting blindly about waving star maps at the prisoners."

"It would have to be a very unusual sky for that to work," Morelles said doubtfully.

"I think it is, Doctor. Tell him about it, George."

George, with plenty of interruptions from Metcalf, and many questions from Morelles, described the strange behavior of his planet's night sky.

"Hmmmm. All right," Dr. Morelles said. "If that isn't strange enough to give us some clues, than it certainly ought to be. I must say, though, that the strangest thing is that none of this came out from all that interrogation you mentioned."

"Well, maybe the powers that be were smarter than anyone thought in putting me on this damned planet," Metcalf said. "I'm the only pilot, the only person who makes his living—and

stays

alive—by looking at the sky and wondering what's out there. The Intelligence teams are trying to backtrack by figuring out the travel times and the number of C

2

jumps the prisoners experienced between Capital and New Finland.

That

won't do them much good. I think that if we can figure out what all this stuff about equatorial lights and vanishing stars

means,

what sort of objects moving how in the sky are required to make things look that way, we can dig through the computer commander and maybe find a system that matches it."

"Yes. I see. You have something there. Please help yourself to more coffee. Let me work on this."

George expected Morelles to go to a computer terminal and start tapping in queries, or at least pull some huge book down from a shelf and mutter to himself as he flipped through it. But Morelles simply leaned back, propped his elbows on the chair arms, cupped his chin in his hands, and stared at the ceiling. The astronomer didn't move but to breathe or blink for a disturbingly long time, until George had thought Morelles might have had some sort of silent stroke and died.

"Were any formal star charts made by the people on Capital?" Morelles asked, interrupting the long silence so abruptly that both George and Metcalf jumped. "Did anyone keep permanent records?"

"Ah, no. It wouldn't have been allowed. We aren't supposed to make up stories about the sky, in the first place. The Central Guardians ruled that folk tales and superstitions were misleading and time-wasters and declared them illegal."

"That sounds like the most un-enforceable law I've ever heard," Morelles growled. "Either your leaders were very sensitive about such things, or they know nothing about psychology."

"I suppose, sir," George said uncomfortably. It was okay when Randall kidded him about home, but he still squirmed when a stranger sneered at the Guardians like that. The evidence of his own eye had forced him to decide the Guardians

did

bad and dumb things, but he couldn't admit they

were

bad, or dumb.

"Do you have any rough idea of the average life span of people on your planet?" Morelles asked.

This guy Morelles must have learned to ask oddball questions in that same place Metcalf had, George thought. "Not really. Not more man seventy or seventy-five in Earth years, I guess. It's news when someone reaches the equivalent of eighty-five or ninety."

"I see. Than we can take perhaps seventy years as the basic upper limit for the survival of Knowledge about one certain patch of sky. Do you see why that's important?"

"No sir," George said.

"I think I've got it, Doctor. Stars don't just appear and disappear. They're permanent. There must be some cyclical pattern of motion of Capital's sky that makes new stars appear and the old ones vanish. This year's new stars

had

to have come by before. If no one remembers seeing the new stars, a human lifetime gives you a lower limit for how long it takes the stars to move once completely around the sky.

"Exactly. I assume that if a person saw a constellation vanish in the west one year and saw an

identical pattern

appear in the new stars of the east, many years later, he could realize that they were one and the same. That seventy years gives me a lower limit for a cycle, three hundred sixty degrees of motion."

"Aha," George said. These guys had lost him again. George was smart enough, plenty smart enough, to understand the motions of the sky, and once he thought about it, it was obvious that stars didn't just vanish. It was just that he never

had

thought about it. Just as the Central Guardians intended, he had never really believed that the points of light in the sky were mighty suns.

"So what is that cycle?" Metcalf asked.

"I should think that would be fairly obvious."

"So call me stupid, Doctor," Metcalf said evenly. "What is it?"

"I would say that Capital's sun is one of a binary pair."

"But sir!" George objected, "even I know what a binary sun is—two stars in orbit around each other. No one back home has ever seen another sun—or even particularly bright star."

"Oh yes you have. What about that glow coming from the north, from over the equator?"

"That's from another

sun?"

"

I

expect so. Does all this make sense to you, Commander Metcalf?"

"Yes sir." Metcalf paused and thought it through. "Except what you're saying is that Capital's north pole is always pretty much pointed at the other star. That's the only way the other star would never be visible from the southern hemisphere of Capital."

"You're quite right, and that

does

suggest a rather odd structure to Capital's star system," Morelles agreed. "But I don't see anything else that fits the facts."

"Sir, if you don't mind my asking," George said, "what sort of odd structure are you talking about?"

"Let me see if I can sum it up. Capital's sun—what do you call it?"

"Nova Sol."

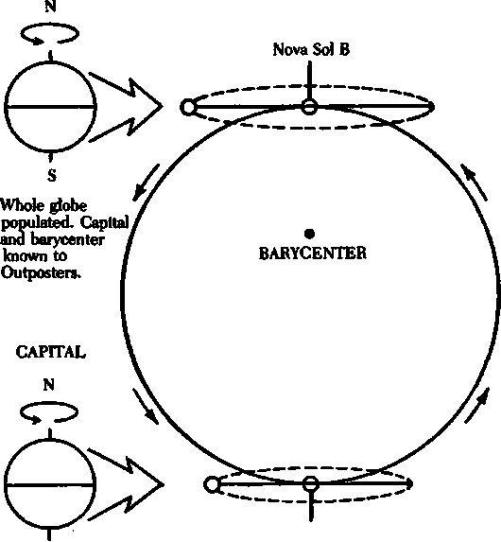

"There must be a dozen stars with that local name in the League. People aren't very original. Very well, Nova Sol is in a binary relationship with another star: The two of them orbit around each other, or more accurately, around an empty spot of space midway between them, where the gravitational attraction of the two stars is exactly balanced. That central balance point is called the barycenter. The two stars revolve around each other in no less than seventy years. Do you understand that so for?"

"Yes. But I can't see how the other star would be hidden all the time."

"Wait a minute, Doctor," Metcalf said. "I think I've got it. Capital's orbit—not the planet, but the

orbit itself—is

precessed, so the orbit is always face-on toward the other sun."

"Precisely!" Morelles grinned with delight. He wished this young naval person was in one of his classes. He was a good thinker.

"Sir," George cut in, "I hate to say it again, but 'huh?' "

Morelles sighed.

That

was more what he was used to. No wonder he preferred research. "Let me see if I can explain." He got up suddenly, went into the next room, and returned with a big sheet of stiff posterboard paper, a pair of scissors, and a marking pen. "I keep this stuff around for notices and posters in the class," he explained. Morelles shoved everything else off his big round coffee table, and George and Metcalf rescued the coffee cups just in the nick of time. Morelles lay the sheet of posterboard down on the table. "All right, now I'll draw this out on cardboard, since I left my blackboard at the classroom."

Morelles, already sketching rapidly on the posterboard, didn't notice that neither of his listeners laughed. "Now then. The usual thing for a solar system is for everything to move in the same plane. I've sketched some of the major element of Earth s solar system here. If you want to represent the orbits of all the planets, except for Pluto, you can just draw them on a flat piece of card as I have done. Within a degree or two, all the orbits are in the same plane. Pluto is the exception that helps explain the rule. Pluto's orbit is, oh dear, what is it? Oh yes, about seventeen degrees away from the plane of the others. If I wanted to show

its

orbit accurately I'd have to take a loop of wire or something and poke it through the cardstock so half the wire loop was above and half was below my flat plane, and then I'd have to set that orbit—that loop of wire—so it was at a seventeen-degree angle to the paper representing the plane of the solar system. Does that give you an idea about the planes of orbits?"

"Yes, I think so," George said. He was beginning to understand, and beginning to be annoyed at the teachers who hadn't shown him this. George, a lover of gadgets and machines and machinery, was getting his first introduction to the greatest clockwork toy there was—the complex and orderly dance of the skies.

"Good," Morelles said. Unconsciously, he had taken on his classroom persona, and all his words and movements became more and more exaggerated. Twenty years of dealing with students had taught him the value of a loud voice, careful enunciation, and expressive hand gestures. "Now, since we've got a large enough piece of card, I can draw a whole other solar system on it, with a sun and planets and satellites and so on. Notice it's all still on one flat piece of paper, everything still moving in one plane. Now I've drawn in the orbits of the planets around the second sun. Let me drawn in one more orbit."

He started his pencil on one of the two suns and drew a wide circle that went through it and the other sun, so that the two of them were one hundred eighty degrees apart. Directly in the center of this big circle, he drew a dot. "That dot is the barycenter, the center of gravity, the balance point for the whole system. Now, imagine the two suns orbiting each other around that barycenter, and the planets orbiting their respective suns, everything in the same plane. This sort of arrangement is what most binary star systems look like. That's clear enough to see. Here s where we get to the unusual features of your Nova Sol system."