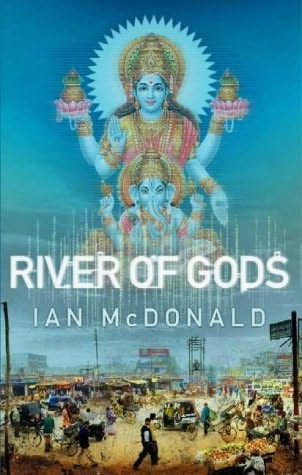

River of Gods

River of Gods

Ian McDonald

1: SHIV

The body turns in the stream. Where the new bridge crosses the Ganga

in five concrete strides, garlands of sticks and plastic snag around

the footings; rafts of river flotsam. For a moment the body might

join them, a dark hunch in the black stream. The smooth flow of water

hauls it, spins it around, shies it feet first through the arch of

steel and traffic. Overhead trucks roar across the high spans. Day

and night, convoys bright with chrome work, gaudy with gods, storm

the bridge into the city, blaring filmi music from their roof

speakers. The shallow water shivers.

Knee-deep in the river, Shiv takes a long draw on his cigarette. Holy

Ganga. You have attained moksha. You are free from the chakra.

Garlands of marigolds coil around his wet pant legs. He watches the

body out of sight, then flicks his cigarette into the night in an arc

of red sparks and wades back towards where the Merc stands axle-deep

in the river. As he sits on the leather rear seat, the boy hands him

his shoes. Good shoes. Good socks, Italian socks. None of your

Bharati shit. Too good to sacrifice to Mother Ganga's silts and

slimes. The kid turns the engine; at the touch of the headlights

wire-thin figures scatter across the white sand. Fucking kids.

They'll have seen.

The big Merc climbs up out of the river, over the cracked mud to the

white sand. Shiv's never seen the river so low. He's never gone with

that Ganga Devi Goddess stuff—it's all right for women but a

raja has

sense

or he is no raja at all—but seeing the

water so low, so weak, he is uncomfortable, like watching blood gush

from a wound in the arm of an old friend that you cannot heal. Bones

crack beneath the SUV's fat tires. The Merc scatters the embers of

the shore kids' fire; then the boy Yogendra throws in the four-wheel

drive and takes them straight up the bank, cutting two furrows

through the fields of marigolds. Five seasons ago he had been a river

kid, squatting by the smudge-fire, poking along the sand, sifting the

silt for rags and pickings. He'll end up there, too, some time. Shiv

will end up there. It's a thing he's always known. Everyone ends up

there. The river bears all away. Mud and skulls.

Eddies roll the body, catch streamers of sari silk and slowly unfurl.

As it nears the low pontoon bridge beneath the crumbling fort at

Ramnagar, the corpse gives a small final roll and shrugs free. A

snake of silk coils out before it, catches on the rounded nose of a

pontoon and streams away on either side. British sappers built this

bridge, in the nation before the nation before this one; fifty

pontoons spanned by a narrow strip of steel. The lighter traffic

crosses here; phatphats, mopeds, motorbikes, bicycle rickshaws, the

occasional Maruti feeling its way between the bicycles, horn

constantly blaring: pedestrians. The pontoon bridge is a ribbon of

sound, an endless magnetic tape reverberating to wheels and feet. The

naked woman's face drifts centimetres beneath the autorickshaws.

Beyond Ramnagar the east bank opens into a broad sandy strand. Here

the naked sadhus build their wicker and bamboo encampments and

practise fierce asceticisms before the dawn swim to the sacred city.

Behind their campfires tall gas plumes blossom skyward from the big

transnational processing plants, throwing long, quivering reflections

across the black river, highlighting the glistening backs of the

buffaloes huddling in the water beneath crumbling Asi Ghat, first of

the holy ghats of Varanasi. Flames bob on the water, a few pilgrims

and tourists have set diyas adrift in their little mango leaf

saucers. They will gather kilometre-by-kilometre, ghat-by-ghat, until

the river is a constellation of currents and ribbons of light,

patterns in which sages scry omens and portents and the fortunes of

nations. They light the woman on her way. They reveal a face of

middle-life. A face of the crowd, a face that would not be missed, if

any face could be indispensable among the city's eleven million. Five

types of people may not be cremated on the burning ghats but are cast

to the river: lepers, childrean, pregnant women, Brahmins, and those

poisoned by the king cobra. Her bindi declares that she is none of

those castes. She slips past, unseen, beyond the jostle of tourist

boats. Her pale hands are soft, unaccustomed to work.

Pyres burn on Manikarnika ghat. Mourners carry a bamboo litter down

the ash-strewn steps and across the cracked mud to the river's edge.

They dip the saffron-wrapped body in the redeeming water, wash it to

make sure no part is untouched. Then it is taken to the pyre. As the

untouchable Doms who run the burning ghat pile wood over the linen

parcel, figures hip-deep in the Ganga sift the water with shallow

wicker bowls, panning gold from the ashes of the dead. Each night on

the ghat where Brahma the Creator made the ten-horse sacrifice, five

Brahmins offer aarti to Mother Ganga. A local hotel pays them each

twenty thousand rupees a month for this ritual but that does not make

their prayers any less zealous. With fire, they puja for rain. It is

three years since the monsoon. Now the blasphemous Awadh dam at Kunda

Khadar turns the last blood in the veins of Ganga Mata to dust. Even

the irreligious and agnostic now throw their rose petals on the

river.

On that other river, the river of tires that knows no drought,

Yogendra steers the big Merc through the wall of sound and motion

that is Varanasi's eternal chakra of traffic. His hand is never off

the horn as he pulls out behind phatphats, steers around cycle

rickshaws, pulls down the wrong side of the road to avoid a cow

chewing an aged vest. Shiv is immune to all traffic regulations

except killing a cow. Street and sidewalk blur: stalls, hot-food

booths, temples, street shrines hung with garlands of marigolds.

Let Our River Run Free!

declares a hand-lettered banner of an

anti-dam protestor. A gang of call-centre boys in best clean shirts

and pants out on the hunt spill into the path of the SUV. Greasy

hands on the paint job. Yogendra screams at their temerity. The flow

of streets grows straiter and more congested until women and pilgrims

must press into walls and doorways to let Shiv through. The air is

heady with alcofuel fumes. It is a royal progress, an assertion.

Clutching the cold-dewed metal flask in his lap, Shiv enters the city

of his name and inheritance.

First there was Kashi: firstborn of cities; sister of Babylon and

Thebes and survivor of both; city of light where the Jyotirlinga of

Siva, the divine generative energy, burst from the earth in a pillar

of radiance. Then it became Varanasi; holiest of cities, consort of

the Goddess Ganga, city of death and pilgrims, enduring through

empires and kingdoms and Rajs and great nations, flowing through time

as its river flows through the great plain of northern India. Behind

it grew New Varanasi; the ramparts and fortresses of the new housing

projects and the glassy, swooping corporate headquarters piling up

behind the palaces and narrow, tangled streets as global dollars

poured into India's bottomless labour well. Then there was a new

nation and Old Varanasi again became legendary Kashi; navel of the

world reborn as South Asia's newest meat Ginza. It is a city of

schizophrenias. Pilgrims jostle Japanese sex tourists in the crammed

streets. Mourners shoulder their dead past the cages of teen hookers.

Skinny Westerners gone native with beads and beards offer head

massages while country girls sign up at the matrimony agencies and

scan the annual income lines on the databases of the desperate.

Hello hello, what country? Ganja ganja Nepali Temple Balls? You

want to see young girl, jig-a-jig; see woman suck tiny little

American football into her little woman? Ten dollar. This make your

dick so big it scares people

. Cards, janampatri, hora chakra,

buttery red tilaks thumbed onto tourists' foreheads. Tween gurus.

Gear! Gear! Knock off sports-stylie, hooky software, repro Big Name

labels, this month's movie releases dubbed over by one man in one

voice in your cousin's bedroom, sweatshop palmers and lighthoeks,

badmash gin and whiskey brewed up in old tanneries (John E. Walker,

most respectable label). Since the monsoon failed, water; by the

bottle, by the cup, by the sip, from tankers and tanks and

shrink-wrapped pallets and plastic litrejohns and backpacks and

goatskin sacks. Those Banglas with their iceberg, you think they'll

give us one drop here in Bharat? Buy and drink.

Past the burning ghat and the Siva temple capsizing slowly,

tectonically, into the Varanasi silts, the river shifts east of

north. A third set of bridge piers stirs the water into cats'

tongues. Lights ripple, the lights of a high-speed shatabdi crossing

the river into Kashi Station. The streamlined express chunks heavily

over the points as the dead woman shoots the rail bridge into clear

war.

There is a third Varanasi beyond Kashi and New Varanasi.

New

Sarnath

, it appears on the plans and press releases of the

architects and their PR companies, trading on the catchet of the

ancient Buddhist city.

Ranapur

to everyone else; a half-built

capital of a fledgling political dynasty. By any name, it is Asia's

biggest building site. The lights never go out. The labour never

ceases. The noise appalls. One hundred thousand people are at work,

from chowkidars to structural engineers. Towers of great beauty and

daring rise from cocoons of bamboo scaffolding, bulldozers sculpt

wide boulevards and avenues shaded by gene-mod ashok trees. New

nations demand new capitals and Ranapur will be a showcase to the

culture, industry, and forward-vision of Bharat. The Sajida Rana

Cultural Centre. The Rajiv Rana conference centre. The Ashok Rana

telecom tower. The museum of modern art. The rapid transit system.

The ministries and civil service departments, the embassies and

consuls, and the other paraphernalia of government. What the British

did for Delhi, the Ranas will do for Varanasi. That's the word from

the building at the heart of it all, the Bharat Sabha, a lotus in

white marble, the Parliament House of the Bharati government, and

Sajida Rana's prime-ministership.

Construction floods glint on the shape in the river. The new ghats

may be marble but the river kids are pure Varanasi. Heads snap up.

Something here. Something light, bright, glinting. Cigarettes are

stubbed. The shore kids dash splashing into the water. They wade

thigh-deep through the shallow, blood-warm water, summoning each

other by whistles. A thing. A body. A woman's body. A naked woman's

body. Nothing new or special in Varanasi but still the water boys

drag the dead woman in to shore. There may be some last value to be

had from her. Jewellery. Gold teeth. Artificial hip joints. The boys

splash through the spray of light from the construction floods,

hauling their prize by the arms up on to the gritty sand. Silver

glints at her throat. Greedy hands reach for a trishul pendant, the

trident of the devotees of Lord Siva. The boys pull back with soft

cries.

From breastbone to pubis, the woman lies open. A coiled mass of gut

and bowel gleams in the light from the construction site. Two short,

hacking cuts have cleanly excised the woman's ovaries.

In his fast German car, Shiv cradles a silver flask, dewed with

condensation, as Yogendra moves him, through the traffic.

Mr. Nandha the Krishna Cop travels this morning by train, in a

first-class car. Mr. Nandha is the only passenger in the first-class

car. The train is a Bharat Rail electric shatabdi express: it piles

down the specially constructed high-speed line at three hundred and

fifty kilometres per hour, leaning into the gentle curves. Villages

roads fields towns temples blur past in the dawn haze that clings

knee-deep to the plain. Mr. Nandha sees none of these. Behind his

tinted window his attention is given over to the virtual pages of the

Bharat Times

. Articles and video reports float above the table as

the lighthoek beats data into his visual lobes. In his auditory

centre: Monteverdi, the Vespers of the Blessed Virgin performed by

the Camerata of Venezia and the Choir of St. Mark's.

Mr. Nandha loves very much the music of the Italian renaissance. Mr.

Nandha is deeply fascinated with all music of the European humanist

tradition. Mr. Nandha considers himself a Renaissance man. So he may

read news of the water and the maybe war and the demonstrations over

the Hanuman statue and the proposed metro station at Sarkhand

Roundabout and the scandal and the gossip and the sports reviews, but

part of his visual cortex the lighthoek can never touch envisions the

piazzas and campaniles of seventeenth-century Cremona.

Mr. Nandha has never been to Cremona. He has never visited Italy. His

imaginings are Planet History Channel establishing shots cut with his

own memories of Varanasi, the city of his birth, and Cambridge, the

city of his intellectual rebirth.