River of Blue Fire (24 page)

Read River of Blue Fire Online

Authors: Tad Williams

Renie flung herself back from the window as a hailstorm of debris clattered along the side of the barn. Bits of roof tile skimmed past her head and shattered against the packing crates. The sound of the wind was dense and deafening. Renie crawled until she felt !Xabbu's hand touch hers. He was shouting, but she could not hear him. They scrambled on their hands and knees toward the rear of the loft, looking for shelter, but all the while something was trying to suck them back toward the open window. Stacks of boxes were vibrating, walking toward the window in tiny, waddling steps. Outside, there was blackness and blur. One of the piles of crates tottered, then tipped over. The boxes bounced once, then were lifted invisibly and yanked through the open window.

“Downstairs!” Renie screamed into the baboon's ear.

She could not tell if !Xabbu heard her above the jet-turbine wail of the tornado, but he tugged her toward the stairwell leading down to the barn floor. The crates had been pulled to the window and were being sucked out. For long instants a cluster of them would stick and the wind in the loft would drop; then the clot would shift loose and spring out into the howling darkness and the wind would do its best to suck Renie and !Xabbu back again.

Grain sacks and tarpaulins flapped toward them like angry ghosts as they half-crawled, half-tumbled down the stairs. The suction was less on the barn floor, but static electricity sparked from the tractors and other equipment, and the great doors leading to the fields were pulsing in and out like lungs. The building shuddered down to its very foundation.

Renie did not remember afterward how they made it across the floor, through the multi-ton pieces of farm equipment shifting like nervous cattle, through the blizzard of loose paper and burlap and dust. They found an open space in the floor, a mechanic's bay for the tractors, and slid over the edge to drop to the oily concrete a few feet below. They huddled against the inner wall and listened as something monstrously powerful and dark and angry did its best to uproot the massive barn and break it to pieces.

It might have been an hour or ten minutes.

“It's getting quieter,” Renie called, and realized she was barely shouting. “I think it's going past.”

!Xabbu cocked his head. “I will know that smell, next time, and we will run to a hiding place. I have never seen such a thing.” The winds were now merely loud. “But it happened so fast. âStorm,' I thought, and then it was upon us. I have never seen weather change so swiftly.”

“It did happen fast.” Renie sat up a little straighter, easing her back. She was, she was only now realizing, bruised and sore all over. “It wasn't natural. One moment, clear skies, thenâwhoosh!”

They waited until the sound of the winds had died completely, then climbed out of the bay. Even in the protected ground floor of the barn, there had been damage: the huge loading doors had been knocked askew, so that a triangle of skyânow blue againâgleamed through the gap. One huge earth grader, in a space nearest to the loft, had been tumbled onto its side like a discarded toy; others had been dragged several yards toward the upstairs window, and lighter debris was strewn everywhere.

Renie was surveying the damage in wonder when a shape slipped in through the damaged loading doors.

“You're here!” Emily shrieked. She ran to Renie and began patting her arms and shoulders. “I was so frightened!”

“It's all right . . .” was all Renie had time to say before Emily interrupted.

“We have to run! Run away! Braincrime! Bodycrime!” She grabbed Renie's wrist and began tugging her toward the doors.

“What are you talking about? !Xabbu!”

!Xabbu loped forward and for a moment there was a strange tug-of-war between the baboon and the young woman, with Renie the thing being tugged. Emily let go and began patting at Renie again, bouncing up and down with anxiety. “But we have to run away!”

“Are you joking? It must be chaos out there. You're safe with us. . . .”

“No, they're after me!”

“Who?”

As if in answer, a line of wide, dark shapes appeared in the doorway. One mechanical man after another stumped through the door, all surprisingly swift, and all buzzing like beehives, until half a dozen had fanned out into a wide circle.

“Them,” said Emily redundantly. “The tiktoks.”

Renie and !Xabbu both thought of the stairs to the loft window, but when they turned they found that mechanical men entering from another part of the barn had already flanked them. Renie feinted back toward the loading doors, but another one of the clockwork creatures stood wedged in the gap there, cutting off escape.

Renie fought down her fury. The stupid girl had led her pursuers right to them, and now they were all trapped. Any one of the mechanical guards had to weigh at least three or four times as much as Renie did, and they also had the advantage of numbers and position. There was nothing to do except hope that whatever happened next would be better. She stood and waited as the buzzing shapes closed in. A foam-lined claw closed on her wrist with surprising delicacy.

“

Bodycrime

,” it said with a voice like an ancient scratched recording. The black glass eyes were even emptier than those of the praying mantis had been. “

Accompany us, please.

”

The tiktoks led them out of the barn into a scene like a medieval painting of hell. The skies had cleared, and once more the sun beat down. Bodies of dead and injured humans, mostly women, lay everywhere in the harsh light. Walls had collapsed, smashing those huddling against them under rubble. Roofs had torn free and swept down the street like mile-a-minute glaciers, grinding everything in their path to jelly and dust.

Several of the tiktoks had been destroyed as well. One seemed to have been dropped from a great height; its remains lay just outside the barn, a sunburst of shattered metal plates and clocksprings thirty feet wide. At the point of impact, part of its torso still held together, including one arm; the hand opened and closed erratically, like the pincer of a dying lobster, as they were marched past.

It did not matter that Renie believed most if not all of the human victims to be animated puppets. The destruction was heart-rending. She hung her head and watched her own feet tramping through the settling dust.

The tornado had missed the farming camp's railyard, although Renie could see the track of its destruction only a few hundred yards away. She and !Xabbu and Emily 22813 were herded onto a boxcar. Their captors stayed with them, which gave Renie pause. Clearly there were fewer functioning tiktoks, or whatever they were called, than there had been half an hour earlier: that six of them should be delegated to guard the two of themâand Emily, too, although Renie doubted that the girl meant much in the larger scheme of thingsâmust mean their crime was considered serious indeed.

Or perhaps just strange, she hoped. The mechanical men were clearly not great thinkers. Perhaps the presence of strangers was so unusual in their simulation that they were having a bit of organizational panic.

The train pulled out of the railyard, rattling and chugging. Renie and !Xabbu sat on the slatted wood floor of the boxcar, waiting for whatever would happen next. Emily at first would only pace back and forth under the dull black eyes of the tiktoks, wringing her hands and weeping, but Renie persuaded her at last to sit down beside them. The girl was distraught, and made almost no sense, mixing bits of babble about the tornado, which she seemed hardly to have noticed, with mysterious ramblings about her medical examination, which she seemed to think was the reason she was in trouble.

She probably said something about us while she was being checked

, Renie decided.

She said the doctors were “henrys

Ӊ

human men. They're probably a bit more observant than these metal thugs

.

The train clacked along. Light flickered on the boxcar's inner wall. Despite her apprehension, Renie found herself nodding. !Xabbu sat beside her, doing something strange with his fingers that at first completely puzzled her. It was only when she woke from a brief doze, and for a moment could not focus her eyes correctly, that she realized he was making string figures with no string.

The trip lasted only a little more than an hour, then they were hauled out of the car by their captors and into a bustling and far bigger railyard. The large buildings of the city Renie had seen earlier loomed directly overhead, and now she could see that they had seemed strange because many of the tallest were only stumps, scorched and shattered by something that must have been even more powerful than the tornado she and !Xabbu had experienced.

The tiktoks led them across the yard, through the gawking throng of worker-henrys in overalls, then loaded Renie and her companions onto the back of a truck. The flatbed took them not into the heart of the blasted city, but along its outskirts to a huge two-story building which seemed entirely made from concrete. They were taken from the truck and into a loading bay, then led into a wide industrial elevator. When they were all inside, the elevator started down without a button being pushed.

The elevator descended for what seemed like minutes, until the soft buzzing of the tiktoks in the elevator car began to make Renie claustrophobic. Emily had been weeping again since they had reached the loading dock, and Renie feared that if it went on much longer she would start screaming at the girl and not be able to stop. As if sensing her distress, !Xabbu reached up and wrapped his long fingers around hers.

The doors opened into blackness, unclarified by the elevator's dim light. Renie's neck prickled. When she and the others did not move, the tiktoks prodded them forward. Renie went slowly, testing the ground with a leading toe, certain that at any moment she would find herself standing at the edge of some terrible pit. Then, when they had taken perhaps two dozen paces, the sound of the tiktoks suddenly changed. Renie whirled in panic. The mechanical men, round shadows with glowing eyes, were backing toward the elevator in unison. As they stepped in and the doors closed, all light went with them.

Emily was sobbing louder now, just beside Renie's left ear.

“Oh, shut

up

!” she snapped. “!Xabbu, where are you?”

As she felt the reassuring touch of his hand again, she became aware for the first time of the background noise, a rhythmic wet squelching. Before she could do more than register this oddity, a light bloomed in the darkness ahead of them. She began to say something, then stopped in astonishment.

The figure before them lolled in a huge chair, which Renie at first thought was carved like an ornate papal throne; it was only as the greenish light grew stronger, pooled on the seated figure, that she could see the chair was festooned with all kinds of tubes, bladders, bottles, pulsing bellows, and clear pipes full of bubbling liquids.

Most of these pipes and tubes seemed to be connected to the figure on the chair, but if they were meant to give it strength, they were not doing their job very well: the thing with the misshapen head seemed barely capable of movement. It turned toward them slowly, rolling its head on the back of the chair. One of the eyes on its masklike face was fixed open as if in surprise; the other gleamed with sharp and cynical interest. A shock of what looked like straw protruded from the top of the head and hung limply down onto the pale, doughy face.

“So you are the strangers.” The voice squelched like rubber boots in mud. It took a deep breath; bellows flapped and farted as it filled its lungs. “It is a pity you have been caught up in all this.”

“Who are you?” Renie demanded. “Why have you kidnapped us? We are just . . .”

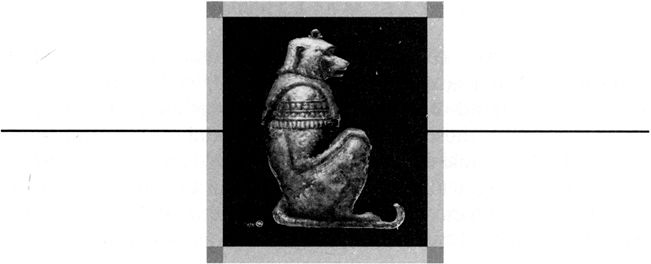

“You are just in the way, I am afraid,” the thing said. “But I suppose I'm being impolite. Welcome to Emerald, formerly New Emerald City. I am Scarecrowâthe king, for my sins.” It made a liquid noise of disgust. Something appeared from the shadows near its feet and scampered back and forth, changing tubes. For a moment, in her numbed astonishment, Renie thought it was !Xabbu, then she noticed that this monkey had tiny wings. “And now I have to deal with this wretched young creature,” the shape on the chair went on, extending a quivering gloved finger at Emily, “who has committed the worst of all bodycrimesâand at a very inconvenient time, too. I'm very disappointed in you, child.”

Emily burst into fresh sobs.

“It

was

her you were after?” Renie was trying to make sense of this. Emerald CityâScarecrowâOz! That old movie! “What are you going to do with

us

, then?”

“Oh, I'll have to execute you, I'm afraid.” The Scarecrow's sagging face curled in a look of mock-sadness. “Terrible, I suppose, but I can't have you running around causing trouble. You see, you've showed up in the middle of a war.” He looked down and flicked the winged monkey with a finger. “Weedle, be a good boy and change my filters, too, will you?”

CHAPTER 10

Small Ghosts

NETFEED/SPORTS: Tiger on a Leash

(visual: Castro practicing with other Tiger players)

VO: Elbatross Castro is only the latest player with a troubled offcourt history to agree to a tracking implant as part of the terms of his huge contract

â

a device that lets his team know where Castro is at any moment and even what he's eating, drinking, smoking, or inhaling

â

but he may be the first to have used jamming equipment on the implant, thus raising a difficult legal issue for the IBA and his team, the Baton Rouge GenFoods Bayou Tigers, last year's North American Conference champions

. . .

W

HILE her mother was looking at some kind of fake person, Christabel turned away from her and scrunched up against the mirror. Wearing her dark glasses indoors, she thought she looked sort of like Hannah Mankiller from the

Inner Spies

show. “Rumpelstiltskin,” she said as loud as she dared. “Rumpelstiltskin!”

“Christabel, what are you doing, mumbling into the mirror? I can't understand a word you're saying.” Her mother looked at her as the fake person continued to talk. Another person in a hurry walked right through the fake woman, who went all wobbly for a moment, like a puddle when you stepped in it, but still did not stop talking.

“Nothing.” Christabel stuck out her lower lip. Her mother made a face back at her and turned to listen to the hollowgran some more.

“I don't like you wearing those indoors,” Mommy said over her shoulder. “Those dark glasses. You'll bump into something.”

“No, I won't.”

“All right, all right.” Her mother took her hand and led her farther into the store. “You must be having one of those difficult phases.”

Christabel guessed that Difficult Faces meant sticking out your lip, but it might also mean not taking off your Storybook Sunglasses. Mister Sellars had said her parents mustn't find out about the special glasses. “My face isn't difficult,” she said, trying to make things better. “I'm just listening to

The Frog Prince

.”

Mommy laughed. “Okay. You win.”

Normally, Christabel loved to go to Seawall Center. It was always fun just to get in the car and go out of the base, but the Seawall Center was almost her favorite place in the world. Only the first time, when she had been

really

little, had she ever not loved it. That time she had thought they were going to the “See Wol Center.” “Wol” was the name Owl called himself in Winnie-the-Pooh, Christabel's favorite stories, and she had waited all day to see Owl. It was only when she started crying on the way back about not seeing him that Mommy told her what the name really was.

The next time it was much better, and all the other times. Daddy always thought it was dumb to drive all the way there, three quarters of an hour each wayâhe always said that, too, “It's three quarters of an hour each way!”âwhen you could get anything you wanted either at the PX or just by ordering, but Mommy said he was wrong. “Only a man would want to go through life without ever feeling a piece of fabric or looking at stitches before buying something,” she told him. And every time she said that, Daddy would make a Difficult Face of his own.

Christabel loved her Daddy, but she knew that her mother was right. It was better than the PX or even the net. The Seawall Center was almost like an amusement parkâin fact, there was an amusement park right inside it. And a round theater where you could see net shows made bigger than her whole house. And cartoon characters that walked or flew along next to you, telling jokes and singing songs, and fake people that appeared and disappeared, and exciting shows happening in the store windows, and all kinds of other things. And there were more stores in the Seawall Center than Christabel could ever have believed there were in the whole world. There were stores that only sold lipstick, and stores that only sold Nanoo Dresses like Ophelia Weiner had, and even one store that sold nothing but oldfashioned dolls. Those dolls didn't move, or talk, or anything, but they were beautiful in a special way. In fact, the store with the dolls was Christabel's favorite, although in a way it was kind of scary, tooâall those eyes that watched you as you came in through the door, all those quiet faces. For her next birthday her mother had even told her she could pick out one of the old-fashioned dolls to be her very own, and even though it was still a long time until her birthday, just coming to Seawall Center to look and wonder which doll she should pick would normally have been the definite best part of the week, so good that she wouldn't have been able to get to sleep last night. But today she was very unhappy, and Mister Sellars wouldn't answer her, and she was really afraid of that strange boy, whom she had seen again last night outside her window.

Christabel and her mother were in a store that sold nothing but things for barbecues when the Frog Prince stopped talking and Mister Sellars' voice took his place. Mommy was looking for something for Daddy. Christabel walked a little way into the store, where her mother could still see her, and pretended to be looking at a big metal thing that looked more like a rocketship from a cartoon than a barbecue.

“

Christabel? Can you hear me

?”

“Uh-huh. I'm in a store.”

“

Can you talk to me now

?”

“Uh-uh. Kind of.”

“

Well, I see you've tried to reach me a couple of times. Is it important

?”

“Yes.” She wanted to tell him everything. The words felt like crawly ants in her mouth, and she wanted to spit them all out, about how the boy had watched her, about why she hadn't told Mister Sellars, because it was her fault she couldn't cut the fence by herslf. She wanted to tell him everything, but a man from the store was walking toward her. “Yes, important.”

“

Very well. Can it be tomorrow? I am very busy with something right now, little Christabel.

”

“Okay.”

“

How about 1500 hours? You can come after school. Is that a good time

?”

“Yeah. I have to go.” She pulled off the Storybook Sunglasses just as the Frog Prince got his voice back.

The store man, who was pudgy and had a mustache, and looked like Daddy's friend Captain Perkins except not so old, showed her a big smile. “Hello, little girl. That's a pretty good-looking machine, isn't it? The Magna-Jet Admiral, that's state of the art. Food never touches the barbecue. Going to get that for your Daddy?”

“I have to go,” she said, and turned and walked back toward her mother.

“You have a nice day, now,” said the man.

Christabel pedaled as fast as she could. She didn't have much time, she knew. She had told her mother that she had to water her tree after school, and Mommy had said she could, but she had to be home by fifteen-thirty.

All of Miss Karman's class had planted trees in the China Friendship Garden. They weren't trees really, not yet, just little green plants, but Miss Karman said that if they watered them, they would definitely be trees some day. Christabel had given hers extra water on the way to school today so that she could go see Mister Sellars.

She pedaled so hard the tires of her bicycle hummed. She looked both ways at every corner, not because she was checking for cars, like her parents had taught her (although she did look for cars) but because she was making sure that the terrible boy wasn't anywhere around. He had told her to bring him food, and she had brought some fruit or some cookies a couple of times and left it, and twice she had saved her lunch from school, but she couldn't go all the way to the little cement houses every day without Mommy asking a lot of questions, so she was sure he was going to come through her window some night and hurt her. She even had nightmares about him rubbing dirt on her, and when he was done, Mommy and Daddy didn't know who she was any more and wouldn't let her in the house, and she had to live outside in the dark and the cold.

When she reached the place where the little cement houses were, it was already three minutes after 15:00 on her Otterland watch. She parked her bike in a different place, by a wall far away from the little houses, then walked really quiet through the trees so she could come in on a different side. Even though Prince Pikapik was holding 15:09 between his paws when she looked at her watch again, she stopped every few steps to look around and listen. She hoped that since she hadn't brought that Cho-Cho boy any food for three days, he would be somewhere else, trying to find something to eat, but she still looked everywhere in case he was hiding in the trees.

Since she didn't see him or hear anything except some birds, she went to the door of the eighth little cement house, counting carefully as she did every time. She unlocked the door and then pulled it closed behind her, although the dark was as scary as her dreams about the dirty boy. It took so long for her hands to find the other door that she was almost crying, then suddenly it pulled open and red light came out.

“Christabel? There you are, my dear. You're lateâI was beginning to worry about you.”

Mister Sellars was sitting in his chair at the bottom of the metal ladder, a small square red flashlight in his hand. He looked just the same as always, long thin neck, burned-up skin, big kind eyes. She started to cry.

“Little Christabel, what's this? Why are you crying, my dear? Here, come down and talk to me.” He reached up his trembly hands to help her down the ladder. She hugged him. Feeling his thin body like a skeleton under his clothes made her cry harder. He patted her head and said “Now then, now then,” over and over.

When she could get her breath, she wiped her nose. “I'm sorry,” she said. “It's all my fault.”

His voice was very soft. “What's all your fault, my young friend? What could you possibly have done that should be worth such suffering?”

“

Oye, weenit, what you got here

?”

Christabel jumped and let out a little scream. She turned and saw the dirty boy kneeling at the top of the ladder, and it scared her so much she wet her pants like a baby.

“

Quien es

, this old freak?” he asked. “Tell,

mija

âwho this?”

Christabel could not talk. Her bad dreams were happening in the real world. She felt pee running down her legs and began to cry again. The boy had a flashlight, too, and he shined it up and down Mister Sellars, who was staring back at him with his mouth hanging open and moving it up and down a little, but with no words coming out.”

“Well, don't matter,

mu'chita

,” the boy said. He had something in his other hand, something sharp. “

No importa

, seen? I got you now. I got you now.”

“O

F

course I understand being careful,” said Mr. Fredericks. He held out his arms, staring at the green surgical scrubs he had been forced to don. “But I still think it's all a bit much.” Jaleel Fredericks was a large man, and when a frown moved across his dark-skinned face it looked like a front of bad weather.

Catur Ramsey put on a counterpoint expression of solicitude. The Frederickses were not his most important clients, but they were close to it, and young enough to be worth years of good business. “It's not really that different from what we have to go through to visit Salome. The hospital's just being careful.”

Fredericks frowned again, perhaps at the use of his daughter's full name. Seeing the frown, his wife Enrica smiled and shook her head, as though someone's wayward child had just spilled food. “Well,” she said, and then seemed to reach the end of her inspiration.

“Where the hell are they, anyway?”

“They phoned and said they'd be a few minutes late,” Ramsey said quickly, and wondered why he was acting as though he were mediating a summit. “I'm sure . . .”

The door to the meeting room swung open, admitting two people, also dressed in hospital scrubs. “I'm sorry we're late,” the woman said. Ramsey thought she was pretty, but he also thought that, with her dark-ringed eyes and hesitant manner, she looked like she'd been through hell. Her slight, bearded husband did not have the genetic good start his wife enjoyed; he just looked exhausted and miserable.

“I'm Vivien Fennis,” the woman said, brushing her long hair back from her face before reaching a hand out to Mrs. Fredericks. “This is my husband, Conrad Gardiner. We really appreciate you coming.”

After everyone, including Ramsey, had shaken hands, and the Gar-dinersâas Vivien insisted they be called for the sake of brevityâhad sat down, Jaleel Fredericks remained standing. “I'm still not sure why we're actually here.” He waved an impatient hand at his wife before she could say anything. “I know your son and my daughter were friends, and I know that something similar has happened to him, to . . . Orlando. But what I don't understand is why we're here. What couldn't we have accomplished over the net?”