Riding Barranca (27 page)

Authors: Laura Chester

Dancing Stallion

We are both relieved to catch a jeep ride back to Camp Bliss where we call our travel agent and alert him to our change of plans. He is very understanding and comes up with an alternate itinerary in a matter of hours.

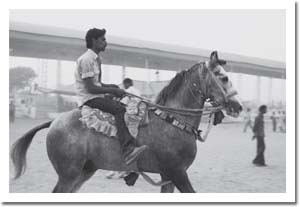

After lunch, we take a camel-cart taxi back to the main arena where we meet up with a young man named “Shom.” He offers to let us ride his two camels back to Camp Bliss in the dusky afternoon light for a small fee of 250 rupees each. From the height of the camels, we get a good view of a dancing stallion that is up on his hind legs, bouncing to the rhythm of the drums, surrounded by a dense crowd of onlookers.

As we work our way back toward our tent camp, we witness a mare being bred. One man holds her tail out of the way while the huge member of the stallion extends. A few plunges and it's over.

“Finito,”

I say, and one of the local men laughs, understanding my meaning.

We pass through the darkening tent city where desert people are huddled about their firesâsmoke rising. I almost feel like I am back in biblical times. Most of the horses are now clothed with makeshift, sackcloth blankets to protect them from the coldâ

same impulse, different budget.

The horses are now busy with their fodder, peacefully eating while shy yet sparkly children wave.

The camel saddle and camel pace is decidedly comfortable, moving me back and forth on my padded perch, a rocking gait that suits me after this morning's trauma. But getting down off a camel feels rather weird as you descend in a three-part motion, as if sitting on a collapsing crane. Back on solid earth, we make plans for Shom to come meet us the following morning so that we can ride through the encampment at sunrise.

Waking early, along with the local roosters, it is nice to be up before everybody else. At the agreed upon time, Shom is there at the gate with his two camels, and up we go, rocking backward and forward in ascension. Shom gives me the two strings that attach to “Johnson's” nose bridleâa strange piercing that works as a nose-bit. It's rather fun steering my camel with these scanty, makeshift reins, while Shom leads Lizbeth up ahead. I am glad to be enjoying this nice rocking gaitâit is very soothing even when Shom gets our mounts to do their own unique, exaggerated form of trotting. We enter the fair grounds and head toward the dunes where most of the camels are traded.

Herds of loose camels are ushered along the hillsides. In the dim light, we ride up to the top of one of the dunes and look down over the huge expanse. Dismounting, we decide to have a cup of morning chai just as the sun appears, blushing over the entire scene.

One young camel lets out a terrible screaming wail, and Shom explains that it is receiving a nose piercing. It sounds excruciating. We then hear whining pipe music and drums down belowâa huddle of men sit in a circle around a couple of baskets. Live cobras rise to the music.

So many of the camels have glamorous saddle sheets or trinket-laden covers, hennaed heads and shaved markings,

anklets and pom-pomsâthe gaudier the better. I tell Shom that I want to buy “Baby Camel Johnson” some decorative necklaces as a way of honoring our guide. He raised this camel since it was just a few months old. No wonder he seems so tame. Shom tells me that I could buy my own camelâit would only cost about $500. I could come back each year and try it out. I imagine that if my father were here, he would be quick to buy a camel just to have something to talk about. “What are they?”

Camels.

“What are they like?”

Steady, plodding, loyal.

Shom selects ten colorful necklaces for a mere 150 rupeesâ(43 rupees to a dollar, so this gift amounts to about $3.50). He ties them onto the camels' long necks, one after another, and the pretty cotton balls of purple, green, pink, and red make a nice effect. The sun is now up, and we want to head back to the arena to see the “camel dancing.”

The performing camels lift their large, split, pancake hooves to the drumbeat. One camel lies down on its side so the trainer can stand on top of him, perhaps to show his dominance over the animal's willing submission. In another unnatural stunt, the camel kneels on its forelegs and crawls forward slowly.

Lizbeth and I begin to feel like we are getting too much sun. The dancing horse performance seems extreme, almost frenzied. It makes me think of the mazurkaâsquatting down and thrusting out the legsâwhich couldn't be easy or healthy for a horse. We decide it is time to stretch our own legs. Dismounting, we say goodbye to Shom and “Baby Camel Johnson,” walking on back to the serenity of Camp Bliss.

Later that day, on our drive to Jodhpur, we stop to have an afternoon cup of chai. While we sit outside in our plastic chairs, waiting for the tea to arrive, our driver explains, “This might take a minuteâthey had to run out and milk their cow.”

Marwari

Sheer stone walls rise forty feet on either side of the entrance to the Raas Hotel, framing the illuminated levels of its amazing courtyard. High above, the massive Mehrangarh Fort rests on top of an impenetrable mountain. We are happy to have our creature comforts: luxurious bathrooms and king-size beds, balconies facing the lit-up fort where dangling lights hang over the ramparts. A small parade goes by on the street below, perhaps part of the bigger wedding party celebration going on in Jodhpur that evening.

There is a sad story behind this wedding. The young thirty-four-year-old prince, Shivraj Singh Ji, was in a serious polo accident five years ago and suffered a brain hemorrhage. He remained in a coma for three months, and while now partially recovered, his health is still severely compromised. He is soon to marry the twenty-two-year-old princess of Jaipur, and as in most royal Indian weddings, this will

be an extravagant, colorful affair that will continue throughout the coming week.

The next day, we catch a taxi out to Rohet Garh, home of the Rajasthani gentleman, Sidharth Singh, who turned his family's fort into a lovely heritage hotel. As we drive from Jodhpur, the landscape appears unremarkable, flat, agricultural, but as we wind our way through the small village toward the entrance to the hotel, I am excited to see the stables straight aheadâthe interior courtyard is padded with soft earth. There is a serene euphony of absence here, a relief to be far from the crowds and pollution and honking horns. We begin to feel very hopeful, sensing that at last we will have a good ride.

The six surrounding stalls of the stable all hold exquisite maresâone has a two-month-old colt with herâand the well-kept horses all turn inward to socialize as any female dormitory would do. When we meet our horseback riding guide, MD, this young trainer has such positive energy that again we are reassured. He tells me that I will be riding a stallion but emphasizes that Arbud is a very gentle horse. We can see that MD takes care with his horses, checking their legs and hocks and unshod feet before we go out.

The owner, Sidharth, greets us with the utmost hospitality, even though he is about to depart for Jaipur by train for the royal wedding. His Yellow Labrador is a bit of a surprise as it is the first fully bred dog I have seen in all of India. Our handsome host is eager for us to have a good ride. Sidharth and his staff have been working to bring the Marwari breed back into good repute, and from what we can tell, they are doing an excellent job. It is now 4:00

P.M.

and we will go out into the fields for a couple hours. It is still warm but not too hot for the horses.

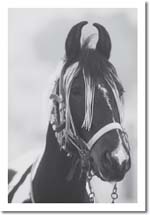

The Marwari were originally used as warrior horses. They are fearless and faithful with terrific stamina and endurance.

I wonder if it will be difficult to hold back my stallion, for as one driver told usâ“What you need in India is a

good horn, good brakes, and good luck.”

But I would addâand a

good horse!

Thankfully, my gentle, grey Marwari stallion has a very delicate mouth. The Pushkar ride damaged my self-confidence, but now it is quickly restored. The saddle fits perfectly, and I am grateful to get another try on a Marwari.

Lizbeth is given a rather spirited black mare who dances about, shying at motorbikes on the way out of town. MD is riding another black mare. Both of these young horses have only been in training for a matter of months. Soon, it becomes apparent that Lizbeth would do better on his horse so they exchange, and then she feels more at ease. Both mares seem more high-strung than my mount, but all of them are beautiful and have not been ruined by rough handling.

Rajasthan had a very good monsoon season this year, which broke a terrible drought. Now, the semi-arid landscape seems moist. The fields of mustard and millet have all been harvested, and the earth is still soft in places. MD is concerned that we have to pick the right place to canter so that the horses won't sink and strain their legs. It is good to be in the hands of a knowledgeable, responsible guide.

I keep my distance from the mares and ride behind as we head out alongside the fields on a soft, dirt road. Tractors and cattle carts pass us. A woman in a bright red sari carries a huge bundle of sticks on her head. Herds of goats graze with a young goatherder in attendance. All is calm and restful.

Lizbeth's horse is named Lakshmi, the goddess of good luck and wealth. She suits Lizbeth perfectly. My friend looks very well-balanced on this lovely mare whose neck is arched, collected. I notice that my horse, Arbud, has a perfect four-beat walking gait, and I take him ahead of the mares for a while,

lifting my reins slightly and leaning back a bit to let him move out. But going first makes the two mares antsy, wanting to race, so I return to the rear. MD explains that the

revaal

gaitâthe running walk we witnessed in the arena at Pushkar (where the riders sat so far back, almost on the horses' rumps, sticking their feet way out in front of them)âis actually quite harmful to the animals. It puts all the rider's weight on the horse's haunches, making the horse lift his head, hollowing out his back. A consistent use of this gait often ruins a horse.

The Revaal

Soon, we are cantering up and down the fields in the dwindling light. My horse has a perfectly relaxed canter. Over and over, I feel waves of relief and pleasure, my confidence restored. The sun is beginning to set, and as I look out across this flat landscape with its occasional acacia, I think of how it is reminiscent of Wisconsin farmland coupled with the exotic elements of Africa, all embraced by the sunset colors of Rajasthan.

MD says the Marwari horse is so fast, “Like a tiger flying after a deerâstretching out like an arrow.”

“I'll race you,” I suggest, and he's game. We spread out across the field and name the finishing point as a small bush two-thirds of the way down the stretch. Then, we are off. Clearly, MD is going to win, but the thrill of our speed is exhilarating.

When the sun is down, rain begins to lightly fall, dampening our shirts. We walk the horses back to the stable in the mellow, dusky evening light.

At the barn, my horse Arbud is housed next to another young stallion. I walk through a paddock of cattle to get to him, wanting to give both horses a few slices of apple. Arbud seems to enjoy his treat, not realizing, in his equine repose, how well he has treated me and how much gratitude I feel for the hospitality and care of Rohet Garh.