Riding Barranca (16 page)

Authors: Laura Chester

“She's crying moon,” Anita laughs.

Only Venus is visible in the dark night sky, crisp and clear, the sinking sun setting off the Patagonia Mountains with a lovely pinkish hue.

Anita and I ride back to the trailers to get her bottle of Pinot Grigio. The horses' hooves spark in the darkness and Saddle Mountain stands out in silhouette. I pick up the long wool coat I have just had cleaned for Helen. It had been so hot this afternoon I didn't think I would need more than a parka vest. Now I am chilled, and the long black coat makes me feel toasty warm and equine elegant.

Back up on the rise, Mason joins us in the Nissan. Anita opens the bottle of wine, passing glasses around. She then cuts some Saga blue cheese to put on crackers. We're all starving. I, for one, have never had wine and cheese on horseback beforeâ

but this is fun!

There is still no sign of the full moon, not even a glimmer, and I am getting tipsy. It is hard to wait for a moon to appear, sort of like

a watched pot doesn't boil.

Maybe, we have to turn our backs on it. Meanwhile, the horses are happily munching. Green grass is beginning to sprout up everywhere thanks to the glorious winter rains. The horses don't seem to mind the novelty of being out in the dark with half-drunk riders.

Finally

Finally, Helen is the first one to spot the moonâway down in the direction of Mexico. What a surpriseâit is actually

nowhere near the Huachucas. Rising over the plain makes the moon's appearance less dramatic than when it rose over the mountains on New Year's Eve. It is now as golden as the sun. “It looks like a peach!” Helen cries, and we are all glad to see it come into view.

We ride back to the horse trailers, Mason transporting our wicker basket filled with food. After loading the horses, we are eager to eat. Anita is especially appreciative that I have brought real linens and a full dinner. We decide on a French picnic out of the back of the car, so that we can see what we are eatingâfried chicken, asparagus, potato salad vinaigrette, red wine, and Mint Milanos.

By half past eight, Mason is ready to head home, while the three of us lie down on the ground and look up at the sky, laughing and carrying on as women do when they're together. A multitude of stars have now appeared overhead. Even though the horses rumble around in their trailers, we are relaxed and hoot when a border patrol van goes byâ“Hide,” I yell. “They'll see us!”

We each have a smoke and puff into the darkness, talking about the art center where Helen teaches. Anita is working on a play with eighteen kids that will be performed in our local Tin Shed. Then, Anita announces that both her father and father-in-law have the same birthdays, and that her mother and mother-in-law both cut off the same index finger while chopping wood. For some reason we find this hilarious.

Helen says that horses sleep in seven-minute segments, and this sounds peculiar but possible, I guess. Where do people get their information? Have our horses dozed off and woken up several times, wondering where they are in the middle of the night while their riders roll around on the ground, delighted by the sight of pristine stars? I have never seen the night sky so clearly.

Keith Warner

Keith and Kacy fly into Tucson from Great Barrington, ready to transport my horses back to Massachusetts. Kacy is astounded by how much Peanut has grown over the winter. He is now just as tall as Barranca, perhaps 16.1 hands, but he is still so skinny he doesn't seem like a very imposing horse.

It is a beautiful, sunny day with only a light breeze. All the mesquite trees have leafed out, and wildflowers surround the trails with sweeps of lavender, red, and yellow. The ocotillos have not fully opened their red tips, poised there on the ends of their tall, spindly wands, but soon they will be in full flower.

Down by the Sonoita Creek, the water is low, but there is still some visual refreshment. A large owl takes off in front of us, and later down the trail we see a pair of gray hawks. Coming onto the long narrow trail where the footing is soft and clean, we enjoy several long canters. A great blue heron lifts off downstream.

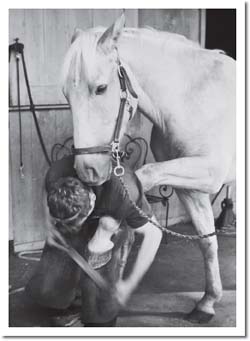

Keith, my farrier, has not ridden much in the past couple of years. “I'm underneath horses all the time, so I don't have much time to get on top of them,” he explains. Back home, Kacy is always trying to get him to ride to no avail, so having him along now is fun for her.

In November, when they made the four-day haul down here with the horses, Keith asked Kacy to marry him out on the front porch of

Casa Durazno.

Now she wears a beautiful engagement ring, and they plan on marrying up at our place on Rose Hill: 09.10.11. That should be easy to remember.

Kacy has been working for me since she was fourteen. Her parents used to drive her up to my barn to muck the stalls, until she got her own car. In her modest, quiet way, she knows more about horses than almost anyone I know. She has won so many blue ribbons that she doesn't even bother to collect them anymore. She is also in charge of the Beinecke barn,

Harmony Hill,

back in South Egremont, Massachusetts, and helps train young riders who want to jump and show, while continuing to take care of my horses when I am away. I feel fortunate to have her and Keith in charge of transporting Barranca and Peanut back East where Rocket is waiting for them. Tonka will stay here in Arizona in a large turnout with many companions, going barefoot until I return.

With his mechanical bent, Keith can fix anything. “He is such a guy,” I exclaim, as he recounts hunting and fishing tales. Kacy agrees, nodding sweetly. He tells us about some

of the games farriers play, including shooting anvils up into the air with explosives.

The sun is intense, and we all agree that we should head backâthey have four long days of hauling ahead of them, and I don't want them to be sore or exhausted as they start out. Riding up the arid trail to the parking lot, I notice that in just a few short hours of midday sun, the ocotillos have begun to fully open, as if some higher power with hot chile breath had exhaled on them. The hillsides are now a sweep of red. “We've got to appreciate beauty wherever we can out here,” I tell them. This might not be as astonishing as New England's autumnal display, but in Arizona, this is about as good as it gets.

We leave the outside barn lights on that night, as they want to leave for Santa Fe at around 5:00

A.M.

when it will still be dark. They should arrive at their first stop no later than 3:00

P.M.,

and will have the afternoon and evening to explore the city.

I kiss my big boy, Barranca, good night, and begin to have separation anxiety, knowing how much I will miss him during the next three weeks. I whisper to him that soon he will be back in the green fields of the Berkshires, and that he should try to endure the long ride. “Horse Heaven is waiting for you,” I tell him. He seems to understand and licks my hand, licks both of them.

It does matter if your horse has a sweet personality. Barranca's loving licks are like kisses. Perhaps he's just searching for salt, but I feel it is heartfelt, especially in contrast to one horse I had years ago.

My dressage trainer at the time convinced me that I should buy this amazing Selle Français-Thoroughbred cross who

was 16.3 hands and very well-educated. From the get-go, he pinned his ears back when anyone approached his stall, but my trainer assured me that a lot of horses had that bad habit.

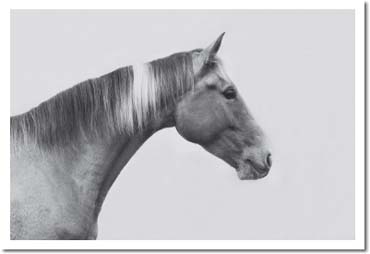

Once I was on him, he seemed nice enough. He had beautiful gaits and could also jump. But when my trainer tried him out, he reared, and she quickly dismounted, as she had already suffered a head injury from a rearing horse and didn't want to get hurt again. Still, I quickly fell for this flea-bitten grey. I named him Nashotah, after a small town in Wisconsin. Having grown up with a difficult mother, I was sure that I could get him to love me if I tried hard enough. But he could never forget whatever it was that had warped his sense of trust.

He developed a foot abscess shortly after I purchased him, and whenever I cross-tied him to dress his wound, he would paw and paw at the rubber mat in the barn. I thought it was an odd habit, but I ignored it, and soon, as he healed, he seemed to paw a bit less, but the ear-pinning continued throughout the rest of his life.

Confused by his behavior, I brought in a horse psychic, and she spent a good deal of time going over him. Without asking me anything about his behavior, she suddenly announced that he had been severely beaten around his legs for pawing in his stall. This had made him defensive. I was amazed. But even given this understanding, there was no changing his behavior. This deep hurt had been stamped into his unforgiving brain, and we never established a heartfelt connection.

It sometimes helps me to remember these things as I try to understand difficult people as wellâto know why they act the way they do, and to try and work around it, not to expect too much. All you can do is give. I have found that when someone lashes out at me, it rarely has anything to do with what I have

done. I have to remind myselfâ

don't take it personally.

There is usually something else going on.

Nashotah passed away in his own good time one winter while I was out in Arizona. Kacy took care of him and had him buried at the foot of the pasture. It was only then that I discovered the ease of my cousin Sarah's gaited horses.

I remember riding her well-trained Tennessee Walker one day in the hills of Colrain. We were moving up a steep incline and I could not believe it. “I feel like I'm dreaming,” I called back to her. “It's like spreading cream cheeseâthis is fantastic! He is so smooth!”

Sarah felt that her horses were also more bombproof than most, possibly because they had been used for hunting. I had been dumped too many times by Nashotah. All it took was the appearance of a leaping deer, or a flapping plastic bag, or one of those terrifying “walking birds” (wild turkeys), and then it was as if a car had hit us broadside.

Now, if something alarms Barranca, he stops in his tracks, stock-still, but he doesn't bolt or hurt me. I imagine what it would be like to lose this horse, how bereft I would be, inconsolable. You might think that an animal could never compensate for the lack of human love, but I disagree. A big-hearted animal can be the greatest consolation.

Looking Toward Home

Even in my sleep I am anxious about this departure. I wake at four in the morning and go see if the trailer is still in the yard. There it is, lit up by the barn lights. But when I finally get up around seven, it is gone, and I feel a pangâa big hole of absence inside me.

Tonka is probably feeling the same thing, locked into his stall. I know he must be worried, left behind, but he lets me brush him down. Tonka looks off in the direction the trailer took earlier this morning. He whinnies out to his friends, but they are long gone, probably passing into southern New Mexico by now. I lead him over to the pasture across the road, and he goes galloping around the field whinnying and searching for his companions.