Rickles' Book (2 page)

Authors: Don Rickles and David Ritz

J

ackson Heights, Queens, was no special place, but my dad, Max, was a special guy. Here’s the kind of guy he was: If he was your friend and came over to your house and your wife was in a housecoat, he could hug her and you wouldn’t think twice. There was nothing distasteful about Max S. Rickles. (I never knew what the “S.” stood for, and neither did he.) Everyone loved my dad. The man was all heart.

Best of all, he laughed at my humor.

He was an insurance salesman who provided for my mother and me, the only child. We weren’t rich, but we weren’t poor. We just were. We lived in a plain apartment like a million other apartments you see in New York City’s five boroughs.

Dad had a lighthearted attitude about life. He took it the way it came. He was the guy who taught me all I know about car repairs: Pay someone to do it for you.

We’d be sitting in our tired old Ford, the engine dead as a doornail. Dad would see someone he knew from our building.

“Charlie,” he’d say, “here’s a couple of bucks. Make the car start.”

He also taught me all I know about home repairs.

Here’s how that worked:

Mom wants to hang a picture.

Max offers the janitor, the mailman—anyone who’s around—a couple of bucks to bang a nail in the wall. No one ever takes the money—they like Max too much—except the janitor, who’s mad because he has to live in the basement.

Max Rickles was a giving sort of man, but sometimes giving isn’t as simple as it seems. I’ll give examples:

We belonged to a little Orthodox synagogue in Jackson Heights, where Dad was an important member. Once he was even president of the congregation. He loved the congregation and fussed over its finances. It was not a wealthy group and the building required maintenance. On the High Holy Days, Dad would escort me and my cousin Allen, who later became a fine doctor, to prime seats near the altar. It turned out to be a land-lease deal. Ten minutes before the start of services, Dad would move us ten rows back. Five minutes later, he’d say, “Okay, guys! Find seats in the back.”

It turned out my father was selling tickets to services like a scalper at a ballgame. He was shuffling around the worshipers and moving some of the higher-donation members to better seats. The proceeds went directly to God.

In this same small synagogue, my lighthearted father was the only one who could deal with the weighty matter of death. When everyone was hysterically crying, Dad would quietly take care of everything. He’d line up the limousines and make the cemetery arrangements. The bereaved families loved him. Dad was able to deal with death. It never frightened him or threw him off track.

Speaking of the track, that was Dad’s one vice. But it wasn’t the kind of vice that did him in. He bet cautiously—two dollars here, two dollars there. He loved the horses. Nothing gave him greater pleasure than winning ten bucks at Belmont.

He also loved many of the customers he sold insurance to. In fact, when they couldn’t cover their insurance payments, he’d often do it for them. He wrote their names in his debit book and carried them on his back. When Dad died of a heart attack in 1953, those same customers came to his funeral and put a box next to his grave where they paid off those debits. That’s how much they respected my dad.

By sheer coincidence, his grave site in Elmont, New York, faces the finish line at Belmont. How’s that for God’s help?

W

hen I was a little kid, being around my mother made me self-conscious. I loved her dearly, but the woman was definitely more commanding in her attitude than most. Etta Rickles had to be the most confident woman in Jackson Heights.

I remember one afternoon when she took me to Radio City Music Hall. As soon as we got on the subway, she announced in her most powerful manner, “We’re getting off at Fiftieth Street!” I immediately felt everyone staring at us.

“Mom,” I said, “talk softer.”

“What softer?” she said in an even stronger voice. “Stop being so self-conscious.”

We arrived at Radio City on this particular Sunday to find a line that went around the block. I had started to walk to the end of the line when Mom stopped me.

“Where we going?” I asked.

“Follow me,” she answered, taking my hand and marching us to the box office.

“Who is that woman?” I heard someone whisper.

“Is she important?” someone else said.

“I’m Mrs. Rickles,” she told the lady in the box office. “And I must see the manager.”

“What do you want with the manager?”

“It is urgent business,” said Mom, “strictly between me and the manager.”

Five minutes later the manager appeared.

“Yes, madam, how can I help you?”

“I’m Mrs. Rickles,” she announced, “and one day my son, Don, here will be a fine entertainer.” When she said that, I hid further behind her.

“We’re loyal patrons of this theater,” she continued. “And we’ve been waiting a very long time and we deserve to be seated now.”

Mom wasn’t mean about it. Her tone was never abrasive. It was simply strong. She was General Patton giving orders. Your reaction was to obey her. And that’s just what the manager did. He personally found us two seats, tenth row center. We watched the Rockettes and then a Ginger Rogers–Fred Astaire movie.

On the way back to Jackson Heights, Mom told me her opinion of the movie, but it seemed to me like she was telling everyone in our subway car.

“It was so glamorous!” she announced. “It was wonderful!”

I wanted to do a magic act and disappear.

Back home, she called her sister, Frieda, to tell her about our adventure. Mom and Aunt Frieda loved each other, but they never stopped arguing. After their conversations, Mom would cry and say, “Why do I argue with my sister when I love her so much?” And the next night the arguing went to level two.

H

igh school studies were always a problem. I couldn’t concentrate on the books. The words “You failed” haunted me like a bad dream. One particular test put me in sugar shock: math.

I hated math. During this exam, I was absolutely lost. So I turned myself into a periscope and aimed my lens one aisle over. I focused on the smartest girl in the class. I was so focused I didn’t noticed the monitor monitoring me. He gave me a look that would have given anyone a nervous breakdown. In a stern voice, he said, “You, what are you doing?”

“What am I doing? I’m cheating,” I said.

Dead silence followed. Some of the kids were proud of me; others felt I needed therapy.

Failure was still my best friend.

Nonetheless, young Don Rickles found a way to keep the applause going. He hung in there, became president of the Dramatic Society, but turned out to be a lousy Julius Caesar.

T

he truth is that I had a hard time getting the girls. That’s because most of the girls were afraid of me and my big mouth. God forbid, if they’d let me get to second base, they worried I’d announce it to Congress.

When I was in my twenties, every weekend me and my pals—Sy and my cousin Jerry—would go to a dance at the Forest Hills Social Hall. This was the forties and the big bands were in their hey-day and kids were jitterbugging to Benny Goodman.

When we arrived at the social hall, crowded with maybe two hundred kids, “Sing! Sing! Sing!” was playing over the loudspeakers. A few couples were jitterbugging, but mostly the girls were just standing around. Some were built pretty good. We wanted to strike up a conversation, but this was the awkward age; no one knew what the hell to say. So we took a drink of VO and ginger ale (known today as diabetes). We wandered around the room, trying not to stare at the girls. But Spider was eager. Spider was dying for action.

“Come on, Don,” urged one of my pals. “Do something funny. Try to get things going.”

I figured, okay, let’s go out in a blaze of glory.

So I stood up on a chair and, right in front of the whole social hall, in a booming voice I shouted, “WE’RE LEAVING!”

Everyone stopped what they were doing.

We left the gym. Two girls were so astounded by the announcement that they followed us outside.

That was one for cousin Jerry, one for Sy, and nothing for me and Spider.

The comedy game was not paying off.

But Rickles marched on.

W

orld War II.

I was eighteen and available. My father said, ��Enlist in the Navy.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Because it’s cleaner than the Army. In the Army, you’ll be rolling around in mud.”

Mud didn’t sound good, so I went with Dad’s advice. In those days, they gave you a pass to graduate. They called it a war diploma. Good thing, because without a war diploma I’d still be in high school.

Everyone was patriotic. I was patriotic, but I had a plan. I was an entertainer. Didn’t matter that the only people I was entertaining were my friends. I’m telling you, I was an entertainer.

With Dad leading the way, I took the subway down to Grand Central Station, where there was a Navy recruiting center at the time.

The doctor took my blood pressure. By the look on his face, I knew something was wrong.

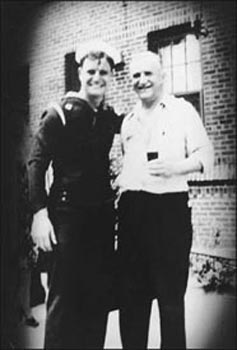

Seaman first class and his dad, Max, March 1943.

“Son,” he asked, “you feeling okay?”

“Feeling fine, sir.”

He took my blood pressure again. The needle went crazy. I looked at the doctor’s expression and figured death was around the corner.

“Lie down, young man,” he ordered.

“Yes, sir.”

The needle started dancing all over my arm—and there was no music.

“You’re staying overnight, son,” he said.

No one stayed overnight at the recruiting center—except me.

My father was upset. “Your mother will really be upset,” he said. “I’m going home to tell her.”

Next morning, the doctor told me I had hypertension. In layman’s talk, that meant I was a wreck. But that didn’t disqualify me. They must have been shorthanded. Go figure.

“I’m an entertainer,” I said to anyone who would listen.

“What kind of entertainer?” the doctor asked.

“Comic. I do impressions. I believe I belong in Special Services.”

“No problem, sailor,” he said, stamping my papers. Bang! Bang! Bang! I’ll never forget that sound.

Next thing I knew, I was on a train with the shades pulled down. The shades were for security reasons but, dummy that I was, I thought we were going to see a movie.

“I’m an entertainer,” I told the commanding officer. “Please send me to where I can entertain.”

“No problem,” he said, stamping my papers with that same Bang! Bang! Bang!

Four hours later, another officer came by with a pad. He asked me if I had special skills.

“Entertaining,” I said proudly. “I’m an entertainer.”

“No problem.” Again with the Bang! Bang! Bang!

Sampson, New York. Boot camp wasn’t fun. Who wants to run around a snowy track in your underwear at five in the morning? Husky dogs couldn’t take it.

“Put me in Special Services, please,” I begged my superiors.

“No problem.” Here we go again. Bang! Bang! Bang!

Next thing I knew I was in the Philippines. The Japanese were on the attack.

“You don’t understand, sir,” I told my commanding officer. “I’m an entertainer. I do impressions.”

He looked at me, looked at my papers, picked up the stamp and came down with a Bang! Bang! Bang!

That night I was sitting with a 20-millimeter gun on a PT tender.

This couldn’t be Special Services. My papers had been stamped, but the only Bang! Bang! Bang! I was hearing was the sound of planes dropping bombs.

Next day, I was back cracking jokes. There were two Jewish boys aboard—me and, believe it or not, a guy louder than me: Irving.

Every Saturday morning while we were anchored in a harbor somewhere in the Philippines, a leaky old whaleboat came by and took me and Irving to worship with a rabbi on shore. That was fine, except that, with the whole crew watching, Irving kept yelling, “Come on, Rickles, the rabbi is waiting!” I felt like I was in the Exodus from Egypt.

I was blessed with a good friend on my ship, Mike Flora. He was like a big brother, a first-class petty officer with lots of class. Mike looked out for me. He got me assigned to the bridge as the captain’s security. Before that, I was scrubbing the deck.

Now picture me carrying a .45, trying to protect the captain. The .45 was only there to make me look important. If the enemy came close to the captain, I would have abandoned ship quicker than you could say “God bless America” and handed the captain the .45.

One night the skipper and I were standing on the bridge. I got up enough nerve to say, “Sir, I believe I belong in Special Services.”

“Not now, son. The Japanese are about to hit us. Put on your helmet and don’t make a sound.”

I put on my helmet, but my hands were shaking. I was so nervous the helmet fell off and went bouncing down the stairwell, making enough racket to be heard in Tokyo.

“Rickles,” the skipper barked, “pull yourself together. How are we supposed to win this war with sailors like you?”

“We’d have a better chance, sir,” I said, “with me in Special Services.”