Richard & John: Kings at War (31 page)

Read Richard & John: Kings at War Online

Authors: Frank McLynn

Meanwhile Henry of Champagne had been busy with an artillery barrage on all the Acre fronts. Yet always the defenders seemed able to rise to the occasion. Several mangonels were destroyed during a sortie and a further two gutted in a sally on the night of ⅔ September.

84

The next attempted target was the Tower of Flies. Pisan soldiers and sailors headed this exploit, which was based on a floating siege tower built on two galleys lashed together. Built around the masts of the galleys, the tower was covered in the usual vinegar-soaked hides and equipped with a ladder. The Pisans came agonisingly close to securing their objective, and there was furious hand-to-hand fighting on the walls of the Tower but, supported by galleys from the city, the garrison finally turned the tide. The floating tower went the way of all Christian structures, being eventually consumed by the naphtha mixture.

85

A fireship attack on the boom of the harbour on 24 September also aborted, when the wind turned, blew the ships back and even helped to consume some of them with their own flames.

86

Saladin’s spies told him there was discord in the Christian camp, with the duke of Swabia (who arrived at Acre on 7 October) being widely unpopular and an effective morale dampener. ‘Would he had not come to us’, was a typical sentiment. Sensing a break-through, Saladin threw everything into a last effort. On 13 November the fiercest battle since Hattin was fought near Haifa, but once again it was indecisive.

87

The crusaders were on some indices close to defeat by the end of the 1190 campaigning season, but their strategic and tactical cluelessness was offset by the steady stream of reinforcements that poured in from the West. Saladin, for all the reasons already mentioned, was unable to deliver the

coup de grâce

, and in some Muslim quarters the feeling grew that sooner or later the combined Christian land and sea forces must prevail over the heroic Acre defenders. At the very time the crusaders were close to total despair, having failed successively with battering rams, floating towers, fireships, trebuchets and mangonels, Saladin’s allies demanded their right to go home for the winter. When he demurred, they started to go anyway; to save face, he was forced to authorise their furlough. Now with a severe manpower shortage, Saladin was obliged to abandon Jaffa, Arsuf and Caesarea. Despondent himself, he ordered all cities he was evacuating, including Sidon, Jubail and Tiberias, demolished. His many Arab critics said he was simply saving the enemy the expense of destroying places they would otherwise have had to besiege.

88

The winter of 1190-91 was in many ways the grimmest experience of the entire siege of Acre. While Richard and his men lolled in Sicily, there was severe hardship among the crusaders at Le Toron. The almost total cessation of shipping in winter inevitably meant food shortages and rocketing prices: the price of an egg rose to sixpence, a single hen cost a year’s pay and the flesh of a dead horse, invariably worth more than a live one, was considered the ultimate delicacy. By Christmas the food shortages had escalated to outright starvation. Offal and animal intestines, disdained in normal times, now became highly prized forms of meat. Bakers’ ovens were overturned and bread plundered, a handful of beans cost a fortune, and men were prepared to commit murder for a square meal.

89

Moreover, since merchant shipping approached Acre from the north, following the coast past Tyre, the egregious Conrad of Montferrat took it into his head to intercept the supply vessels and hold the food in his city to bring leverage on the crusader leaders to accede to his demands (this was the time of the scandalous marriage to Isabella). Before long, even the nobility were reduced to eating grass, herbs and plants. The staple was the carob bean, the edible pods of the evergreen carob tree, which was found everywhere in the Mediterranean and known as St John’s bread, though normally fed only to animals. Soon disease, the constant concomitant of starvation, made its appearance, exacerbated by the teeming winter rains.

90

Initially it was scurvy and gingivitis that caused the damage, but soon outright plague was raging through the Christian army and carrying off up to two hundred men a day. Exact statistics for the ravages of pestilence and disease cannot be retrieved, but an inference on generally high mortality can be made from the large numbers of Frankish ‘celebrities’ who died at Acre or from the consequences of the siege. These included the duke of Swabia, Archbishop Baldwin, Gérard de Rideford, Philip of Alsace, count of Flanders, Hellin of Wavrin, the seneschal of Flanders, Ludwig III, Landgrave of Thuringia, Henry, count of Bar-le-Duc, William Ferrers, earl of Derby, Thorel of Mesnil (a Norman magnate), count Theobald of Blois, Stephen, count of Sancerre, Ralph, count of Clermont and a host of lesser barons.

91

On 31 December 1190 an Egyptian flotilla made a sustained attempt to break the blockade around Acre but all seven vessels were lost to a combination of crusader counter-attack, reefs and storms. A week later part of the city wall collapsed, destroying part of the outworks. The Franks poured through the gap and were beaten back only with supreme difficulty; it was more the rain-sodden earth and the starved condition of their men and horses that beat them than the valour of the defenders. When the crusaders fell back exhausted, the Muslims were able to repair the breach by building a retaining wall. Conrad then made another assault on the Tower of Flies, which the Muslims again only just repelled.

92

Saladin’s problems were multiplying. Already he was running short of weapons, and his appeals for reinforcement to the Caliph became increasingly strident, but to no greater effect than before. The Almohads, far from helping him, actually opened their ports to the Genoese. His most talented commander, Taqui al-Din, would shortly desert him to pursue his own interests in Armenia. Saladin’s own health was deteriorating badly.

93

After nearly eighteen months of siege, in which both sides had exercised technical ingenuity to the limit, Christians and Muslims were stalemated. This was the context in which Philip of France arrived in Acre on 20 April with six large transports. Although the crusaders were initially disappointed at the small forces he had brought with him, he promised that this was merely a vanguard and that Richard would soon be with them. Philip had it trumpeted about the encampment that he was under a pledge to wait for Richard before the assault proper began, but he started a mangonel bombardment of the Accursed Tower. On 30 May Saladin had to make a forced march of fourteen miles to relieve the hard-pressed garrison.

94

With the military situation on a knife edge, it was obvious to both sides that Richard would tip the balance. Saladin still trusted in his God to see him through, but even he baulked at the thought of meeting Christendom’s ‘king of kings’, reputedly the greatest captain in the West. The warriors of God were about to clash mightily.

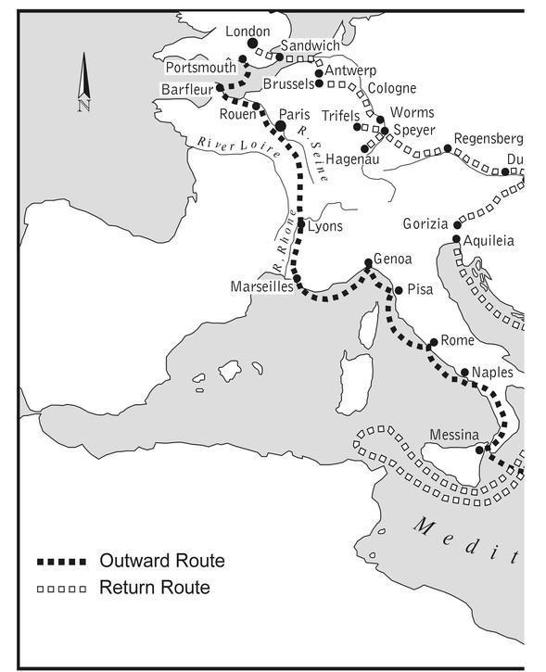

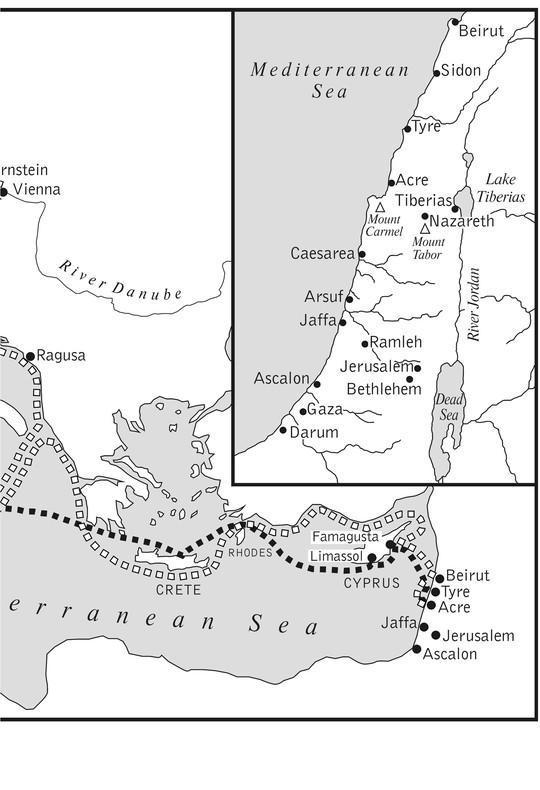

2. The Mediterranean and Palestine, showing Richard’s journey during the Crusade

8

ON 5 JUNE RICHARD and his knights, in company with Guy of Lusignan and his entourage, set sail from Famagusta for the short trip to the Asian mainland. He landed near the great castle of Margat and handed Isaac over to the Knights of St John. Continuing south, he was at Tyre next day, but the garrison, acting on orders from Conrad of Montferrat, refused him admission.

1

On the final leg to Acre, Richard’s fleet intercepted a huge Muslim supply ship from Beirut, a massive three-masted red and yellow buss. It was packed with troops, said to number 350, and to have as cargo one hundred camel-loads of weapons, quantities of Greek fire in bottles, and two hundred poisonous snakes, which were to be used in the old Byzantine way as missiles to be hurled at the enemy from catapults.

2

With a favourable wind this vessel should easily have been able to evade Richard’s twenty galleys but, as luck would have it, the wind dropped, allowing the crusaders to close with it. At first the Muslim ship inflicted losses through greater long-range missile power, but Richard urged on his men, they grappled, and soon the enemy vessel was sinking. The crusaders claimed the credit, but Muslim sources allege that the captain simply scuttled his craft once he saw that capture was inevitable.

3

Out of a large ship’s complement, maybe three hundred men when we have scaled down the usual medieval exaggerations, only about thirty-five escaped drowning when Richard chivalrously plucked them from the waves. There is no doubt that this exploit lost nothing in the telling and was ‘talked up’ by the chroniclers, to the point where it is alleged that Acre would not have fallen if the ship had got through.

4

Yet the psychological effect was undeniable. In his first action against the Saracens Richard had scored a victory and this augured well. Philip’s arrival two months earlier with an exiguous force had greatly encouraged the Muslims, and he had not made much of an impression thereafter, despite the ludicrous assertion of his propagandists that Acre would have fallen by his efforts alone had he not chivalrously decided to delay the final assault until Richard’s arrival.

5

The plain truth is that Philip’s attack on the Accursed Tower was a failure, with the defenders managing to burn some of his siege engines. Even filling up the ditches on the city’s approaches cost the Christians dear, and they were reduced to throwing their dead into the fosse to make a more solid foundation. Philip as augur of ill-fortune seemed confirmed by a singular bad omen: his rare and magnificent white falcon, his pride and joy, flew away from him, ignored calls to return and perched defiantly on the walls of Acre.

6

Richard’s arrival at Acre on 8 June, with twenty-five ships, heartened the Frankish attackers and dismayed the Saracens. Since Arab historians say that each one of the vessels was ‘as big as a citadel’, scholars wonder whether he had not re-equipped his fleet in Cyprus and even built a new kind of ship, maybe something like the galleys of the fifteenth century.

7

But the simple fact that he had secured a supply line to Cyprus, arrived with massive reinforcements, and won a naval battle into the bargain, pitched the Christians into euphoria. The night of 8-9 June saw the crusader camp a riot of celebration, as drunken soldiery danced dizzily by the light of flambeaux or flickering bonfires. The spirits of the Saracens drooped correspondingly.

8

Yet Richard still awaited most of his transports carrying the siege engines, and for this reason declined the French king’s proposal that they launch a joint attack immediately. Sullenly Philip ordered the offensive anyway; Richard’s troops simply guarded the flanks and outer trenches against any Muslim counter-attack. As Richard had foreseen, the unilateral French assault failed, even though Geoffrey de Lusignan distinguished himself in the action and won a reputation as the finest knight in the field.

9

Meanwhile Richard’s fleet intercepted a Saracen flotilla from Beirut bringing supplies and 700 fighting men; the destruction of these ships cast the Arabs further into despondency. There were ferocious attacks on Acre on 9, 14 and 18 June by Philip which petered out in the midday heat, but finally Richard’s siege engines and trebuchets arrived from Tyre, and the pressure on the city intensified. Richard even had a new kind of stone he had brought from Cyprus which did not shatter on impact and was thus a more lethal artillery. His tactics were twofold. While his offensive concentrated on demolishing the Accursed Tower by artillery bombardments and undermining, he aimed to demoralise the defenders by sheer attrition, since the crusaders now had superior numbers and equipment. By 24 June the Acre garrison was desperate and on the point of surrender.

10