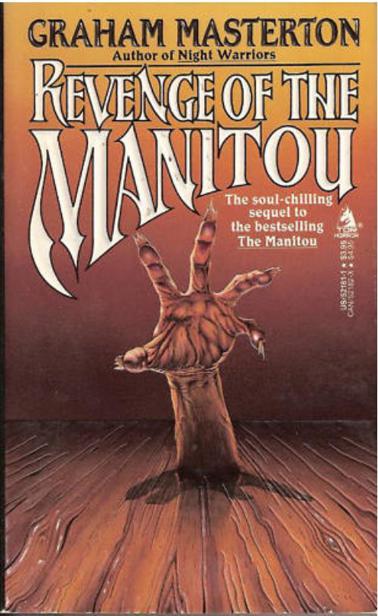

Revenge of the Manitou

Revenge

of the Manitou

By

Graham

Masterton

H

e woke up during the night and he was sure there was someone in

his room.

He froze, not

daring to breathe, his eight-year-old fingers clutching the candy-striped sheet

right up to his nose. He strained his eyes and his ears in the darkness,

looking and listening for the slightest movement, the slightest squeak of

floorboards. His pulse raced silently and endlessly, a steeplechase of boyish

terror that ran up every artery and down every vein.

“Daddy” he

said, but the word came out so quietly that nobody could have heard him. His

parents were sleeping right down at the other end of the corridor, and that

meant safety was two doors and thirty feet away, across a gloomy landing where

an old grandfather clock ticked, and where even in daytime there was a curious

sense of solitude and suffocating stillness.

He was sure he

could hear somebody sighing, or breathing. Soft, suppressed sighs, as if they

meant sadness, or pain. It may have been nothing more than the rustle of the

curtains, as they rose and fell in the draft from the half-open window. Or it

may have been the sea, sliding and whispering over the dark beach, just a

half-mile away.

He waited and

waited, but nothing happened. Five minutes passed.

Ten.

He lifted his blond, tousled head from the pillow, and looked around the room

with widened eyes. There was the carved pine footboard, at the end of his bed.

There was the walnut wardrobe. There was his toy box, its lid only half-closed

because of the model tanks and cranes and baseball gloves that were always

crammed in there.

There were his

clothes, his jeans and his T-shirt, over the back of his upright ladder-backed

chair.

He waited a

little longer, frowning. Then he carefully climbed out of bed, and walked

across to the window. Outside, under a grayish sky of torn clouds and fitful

predawn winds, a night heron called

kwawk

,

kwawk

, and a wooden door banged and banged. He looked down

at the untidy backyard, and the leaning fence that separated the

Fenners

’ house from the grassy dunes of the Sonoma

coastline. There was nobody there.

He went back to

bed, and pulled the sheets almost over his head. He knew it was silly, because

his daddy had told him it was silly. But somehow tonight was different from

those times when he was just afraid of the shadows, or overexcited from

watching flying-saucer movies on television.

Tonight, there

was someone there.

Someone who sighed.

He lay there

tense for nearly twenty minutes. The wooden door kept banging, with mindless

regularity, but he didn’t hear anything else. After a while, his eyes began to

close. He jerked awake once, but then they closed again, and he slept.

It was the

worst nightmare he had ever had. It didn’t seem as though he was dreaming at

all. He rose from his bed, and turned toward the wardrobe, his head moving in

an odd, stiff way. The grain of the walnut on the wardrobe doors had always

disturbed him a little, because it was figured with foxlike faces. Now, it was

terrifying. It seemed as if there was someone inside the surface of the wood,

someone who was calling out to him, trying desperately to tell him something.

Someone who was trapped, but also frightening.

He could hear a

voice, like the voice of someone speaking through a thick glass window. “Alien...

Alien... for God’s sake, Alien... for God’s sake, help me... Alien...,” the

voice called.

The boy went

closer to the wardrobe, one hand raised in front of him, as if he was going to

touch the wood to find where the voice was coming from. Dimly, scarcely visible

except as a faint luminosity on the varnish, he could make out a gray face, a

face whose lips were moving in a blurry plea for mercy, for assistance, for

some way out of an unimaginable hell.

“Alien…”

pleaded the voice, monotonously. “Alien... for God’s sake...”

The boy

whispered, “Who’s Alien? Who’s Alien? My name’s Toby. I’m Toby

Fenner

. Who’s Alien?”

He could see

the face was fading. And yet, for one moment, he had an indescribable sense of

freezing dread, as if a cold wind had blown across him from years and years

ago. There was a feeling of someplace else... someplace known and familiar and

yet frighteningly strange. The feeling was there and it was gone, so quickly

that he couldn’t grasp what it was.

He banged his

hands against the wardrobe door and said, “Who’s Alien? Who’s Alien?”

He was more and

more alarmed, and he screeched at the top of his high-pitched voice, “Who’s

Alien? Who’s Alien? Who’s Alien?”

The bedroom

door burst open and his daddy said, “Toby? Toby-what in hell’s the matter?”

Over breakfast

at the pine kitchen table, bacon and eggs and pancakes, his daddy sat munching

and drinking coffee and watching him fixedly. The San Francisco Examiner lay

folded and unread next to his elbow. Toby, already dressed for school in a

pale-blue summer shirt and jeans, concentrated his attention on his pancakes.

Today, they were treasure islands on a sea of syrup, gradually being excavated

by a giant fork.

At the kitchen

stove, his mommy was cleaning up. She was wearing her pink gingham print apron,

and her blond hair was tied back in a ponytail. She was slim and young and she

cooked bacon just the way Toby liked it. His daddy was darker and quieter, and

spoke slower, but there was deep affection between them which didn’t have much

need of words. They could fly kites all Sunday afternoon on the shoreline, or

go fishing in one of the boats from his daddy’s boatyard, and say no more than

five words between lunch and dusk.

Through the kitchen

window, the sky was a pattern of white clouds and blue. It was September on the

north California shore, warm and windy, a time when the sand blew between the

rough

grass,

and the laundry snapped on the line.

Susan

Fenner

said, “More coffee? It’s all fresh.”

Neil

Fenner

raised his cup without taking his eyes off Toby.

“Sure. I’d love some.”

Susan glanced

at Toby as she filled her husband’s cup. “Are you going to eat those pancakes

or what?” she asked him, a little sharply.

Toby looked up.

His daddy said, “Eat your pancakes.” Toby obeyed. The treasure islands were dug

up by the giant fork, and shoveled into a monster grinder.

Susan said,

“Anything in the paper this morning?”

Neil glanced at

it, and shook his head.

“You’re not

going to read it?” Susan asked, pulling out one of the pine kitchen chairs and

sitting down with her cup of coffee. She never ate breakfast herself, although

she wouldn’t let Neil or Toby out of the house without a good cooked meal

inside them. She knew that Neil usually forgot to take his lunch break, and

that Toby traded his peanut-butter sandwiches for plastic GIs or bubble gum.

Neil said no,

and passed the paper across the table. Susan opened it and turned to the

Homecraft

section.

“Would you

believe this?” she said. “It says that Cuisinart cookery is going out of style.

And I don’t even have a Cuisinart yet.”

“In that case,

we’ve saved ourselves some money,” said Neil, but he didn’t sound as if he was

really interested. Susan looked up at him and frowned.

“Is anything

wrong, Neil?” she asked.

He shook his

head. But then he suddenly reached across the table and held Toby’s wrist, so

that the boy’s next forkful of pancake was held poised over his plate. Toby

said, “Sir?”

Neil looked at

his son carefully and intensely. In a husky voice, he said, “Toby, do you know

who Alien is?”

Toby looked at

his father uncomprehendingly.

“Alien, sir?”

“That’s right.

You were saying his name last night, when you were having that nightmare. You

were saying ‘I’m not Alien, I’m Toby.’ “

Toby blinked. In

the light of day, he didn’t remember the nightmare very clearly at all. He had

a sense that it was something to do with the wardrobe door, but he couldn’t

quite think what it was. He remembered a feeling of fright. He remembered

bis

daddy putting him back to bed,

and tucking him in tightly. But the name “Alien” didn’t mean anything.

Susan said,

“Was that what he was saying? ‘I’m not Alien, I’m Toby’?”

Neil nodded.

“But kids say

all kinds of silly things in their sleep,” she told him. “My younger sister used

to sing nursery rhymes in her sleep.”

“This wasn’t

the same,” said Neil.

Susan looked at

Toby and then back to her husband. She said quietly, “I don’t know what you

mean.”

Neil let go of

his son’s wrist. He dropped his eyes toward the table, at his scraped-clean

plate, and then said, “My brother’s name was Alien. Everybody used to call him

Jim on account of his second name, James. But his first name was Alien.”

“But Toby

doesn’t know that.”

Neil said, “I

know.”

There was an

awkward silence. Then Susan said, “What are you trying to say? That Toby’s

having nightmares about your brother?”

“I don’t know

what I’m trying to say. It just shocked me,

that’s

all. Toby’s room used to be Alien’s. Jim’s, I mean.”

Susan put down

her cup of coffee. She looked at Neil and she could see that he wasn’t pulling

her leg. He did, sometimes, with fond but heavy-handed humor which he’d

inherited from his Polish mother. Good old middle-European practical jokes. But

today, he was edgy and disturbed as if he’d had a premonition of unsettled days

ahead.

Susan said,

“You think it’s a ghost, or something?”

Neil looked

serious for a moment, and then gave a sheepish grin, and shrugged.

“Ghost?

I don’t know. I don’t believe in ghosts. I mean, I don’t

believe in ghosts that wander around in the night.”

Toby piped up,

“Is there a ghost, Daddy?

A real ghost?”

Neil said, “No,

Toby. There isn’t any such thing. They come out of storybooks, and that’s all.”

“I heard some

noises in the night,” Toby told him. “Was that a ghost?”

“No, son.

It was just the wind.”

“But what you

said about Alien?”

Neil lowered

his head. Susan took Toby’s hand and said softly, “Daddy was just saying that

you must have had a very special kind of dream, that’s all. It’s nothing to get

frightened about. Now, are you going to finish that pancake, because it’s time

for

school.

”

Neil drove Toby

in his Chevy pickup as far as Bodega Bay, and dropped him off at the

schoolhouse. The bell was ringing plaintively, and most of the kids were already

in the building.

Toby climbed

down to the road, but instead of running straight into school, he stood beside

the truck for a moment, looking up at his father. His blond hair was ruffled by

the Pacific wind. He said, “Daddy?”

Neil looked at

him. “What’s the matter?” Toby said, “I didn’t mean to upset you or anything.”

Neil laughed.

“Upset me? You haven’t upset me.” “I thought you were. Mommy said I mustn’t

talk about Jim.”

Neil didn’t

answer. It was still difficult for him to think about his brother. He no longer

got those terrible, clear pictures in his mind. He’d managed, with time, to

blur them beyond recognition. But there was still that sensation of breathless

pain, like jumping into the ocean on a December day. There was still that

helplessness, still that desperation.

Neil said,

“You’d better get into school. The teacher’s going to be worrying where you

are.”

Toby hesitated.

Neil continued, “Go along, now,” and Toby knew that his daddy meant it. He

swung his books and his lunch pail over his shoulder and walked slowly across

the gray, dusty yard. Neil watched him go into the battered pale-blue door, and

then the door swung shut. He sighed.

He knew that he

ought to be straight with Toby, and tell him about Jim. But somehow he

couldn’t, not until he could get straight about Jim in his own mind. He’d

begun, a couple of times, to try and tell Toby what had happened; but the words

always came out wrong. What words could there possibly be to describe the

experience of watching your own brother being slowly crushed to death under an

automobile? What words could there possibly be to describe the knowledge that

it was your fault, that you’d accidentally released the jack?

He could see

Jim’s hand reaching out to him even today. He could see Jim’s pleading, swollen

face, with the blood running from his mouth and his nose. How do you tell your

eight-year-old kid about that?