Restless Giant: The United States From Watergate to Bush v. Gore (66 page)

Read Restless Giant: The United States From Watergate to Bush v. Gore Online

Authors: James T. Patterson

Tags: #20th Century, #Oxford History of the United States, #American History, #History, #Retail

When Gore heard the networks announce for Bush, he rang him up to offer congratulations, only to be alerted by aides that he still had a good chance in Florida. So he phoned Bush back, saying: “Circumstances have changed dramatically since I first called you. The state of Florida is too close to call.” Bush responded that the networks had confirmed the result and that his brother, Jeb, who was Florida’s Republican governor, had told him that the numbers in Florida were correct. “Your little brother,” Gore is said to have replied, “is not the ultimate authority on this.”

54

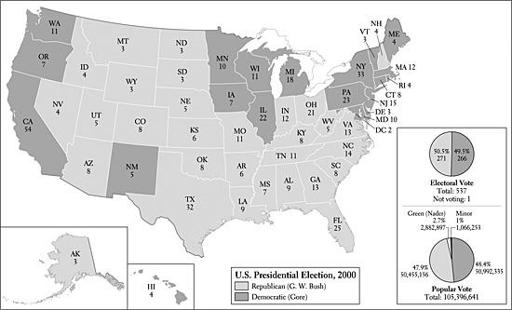

Americans, having gone to bed not knowing which candidate had won, awoke the next day to learn that the outcome was still uncertain. Within a few days, however, it seemed that Gore was assured of 267 electoral college votes, three short of the number needed to win the election. Bush then appeared to have 246. The eyes of politically engaged Americans quickly shifted to Florida, where twenty-five electoral votes remained at stake. If Bush could win there, where the first “final count” gave him a margin of 1,784 votes (out of more than 5.9 million cast in the state), he would have at least 271 electoral votes. Whoever won Florida would become the next president.

There followed thirty-six days of frenetic political and legal maneuvering, which all but eclipsed media attention to last-ditch efforts—in the end unsuccessful—that the Clinton administration was undertaking at the time to fashion an agreement between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization.

55

Much of the electoral maneuvering during these five weeks featured partisan disputes over poorly constructed ballots used in various Florida counties. Flaws such as these, which had long existed throughout the United States, reflected the idiosyncratic and error-prone quality of America’s voting procedures, which state and local authorities determined, but they fell under an especially harsh glare of public scrutiny only in 2000. In predominantly Democratic Palm Beach County, for instance, more than 3,000 voters—many of them elderly Jews—were apparently confused by so-called butterfly ballots and mistakenly voted for Buchanan, the Reform Party nominee, instead of for Gore. Some voters there, bewildered by the ballots, punched more than one hole; these “overvotes,” like thousands of overvotes on variously constructed ballots in other counties, were not validated at the time.

Elsewhere, partially punched ballots emerged from voting machines, leaving “hanging,” “dimpled,” “pregnant,” or other kinds of “chads.” In the parlance of the time, these were “undervotes”—that is, ballots that voters may well have tried to have punched but that voting machines did not record as valid at the time.

56

It was estimated that the total of disputed undervotes (61,000) and overvotes (113,000) in Florida was in the range of 175,000. Irate Democrats further charged that officials at the polls unfairly invalidated the registrations of thousands of African American and Latino voters and tossed out a great many ballots in predominantly black neighborhoods. Police, they claimed, intimidated blacks who therefore backed away from voting in some northern Florida counties.

57

Gore’s supporters further alleged that thousands of Floridians, many of whom were African American, were inaccurately included on long lists of felons and therefore denied the franchise under Florida law. Angry controversies over issues such as these heated up partisan warfare that raged throughout the nation.

58

From the beginning, Bush backers, led by former secretary of state James Baker, worked as a disciplined team in the post-election struggles involving Florida. By contrast, the Democrats, headed by former secretary of state Warren Christopher, were cautious, even defeatist at times.

59

Baker’s team relied especially on the efforts of Bush’s brother, Jeb, and on the Republican-controlled Florida legislature, which stood ready to certify GOP electors. Federal law, Republicans maintained, set December 12 (six days before America’s electors were to vote on December 18) as a deadline after which Congress was not supposed to challenge previously certified electors. If Gore called for a manual recount of ballots, Republicans clearly planned to turn for help to the courts in an effort to stop such a process or to tie it up in litigation so that no resolution of the controversy could be achieved by December 12.

Two days after the election, by which time late-arriving overseas ballots and machine recounts (required by Florida law in a close election such as this) had managed to cut Bush’s lead, Gore’s team acted, seeking hand recounts in four predominantly Democratic counties where punch-card ballots had failed to register the clear intent of many voters. In limiting their focus to four counties, Gore’s advocates maintained that Florida law did not permit them to call at that time for a statewide recount. Such a statewide process, they said, could then be legally undertaken only in counties where substantial errors were perceived to have occurred. Still, Gore’s move seemed to be politically opportunistic. Seizing the high ground, Bush defenders accused him of cherry-picking Democratic strongholds.

On November 21, the Florida Supreme Court intervened on behalf of Gore, unanimously approving manual recounts in the four counties and extending to November 26 (or November 27, if so authorized by Florida’s secretary of state, Katherine Harris) the deadline for these to be completed. Furious Bush supporters immediately responded by charging that Florida’s Democratic judges, apparently a majority on the court, were trying to “steal” the election. Manual recounts of this sort, the GOP insisted, would be “arbitrary, standardless, and selective.” With tempestuous disputes flaring between hosts of lawyers and party leaders who were hovering over exhausted recount officials, Republicans on November 22 submitted a brief along these lines asking the United States Supreme Court to review the issue. The Court quickly agreed to do so and set December 1 as the date for oral argument.

As Democrats complained, the Bush team’s appeal to the Supreme Court was ideologically inconsistent, inasmuch as Republicans, professing to be advocates of states’ rights, normally argued that state courts should be the interpreters of state laws, including election laws. So had the conservative Republicans on the U.S. Supreme Court. The GOP, Democrats charged, was jettisoning its ideological position and relying on crass and cynical political tactics aimed at subverting the will of Florida voters.

Republicans also insisted in their brief that the Florida court had changed the rules after the election and that it had violated Article II of the United States Constitution, which said that state legislatures, not state courts, were authorized to determine the manner in which electors were named.

60

Their brief further maintained, though at less length than in its reliance on Article II, that recount officials in the selected counties would treat ballots differently and therefore violate voters’ “equal protection” under the law, as guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. Republicans also continued to rely on Secretary of State Harris, who had been a co-chair of the Bush campaign in the state. As Harris had said she would do, she stopped the manual recounts on November 26 and certified that Bush had taken Florida, by the then narrow margin of 537 votes. Because Miami-Dade and Palm Beach County officials had not completed their recounts, many disputed ballots in those populous areas were not included in the final tallies that she had certified.

Though Bush hailed this certification, proclaiming that it gave him victory, Gore’s lawyers predictably and furiously contested it. Attacking the GOP brief that was before the U.S. Supreme Court, they also insisted that the Florida legislature (which the Bush team, relying on Article II of the U.S. Constitution, was counting upon if necessary) did not have the authority to override Florida state law and the state constitution, which provided for judicial review of the issue by the state courts.

During the oral presentations on December 1 of arguments such as these, it was obvious that the High Court was deeply divided. It responded on December 4 by sending the case back to the Florida Supreme Court and asking it to explain whether it had “considered the relevant portions of the federal Constitution and law.”

61

The justices said nothing at the time concerning the Bush team’s assertion that the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment was relevant to the case. Nor did the Court indicate that it might regard establishment of specific and uniform recounting standards as the key matters in its decision.

The Florida court, essentially ignoring the High Court’s directive, replied on December 8 by ordering, on a vote of four to three, that a statewide hand recount be undertaken of the 61,000 or so undervotes that were contested. The four-judge majority did not outline specific standards that would indicate which ballots should be accepted. In deciding which ballots were acceptable, the judges said, recount officials should take into account the “clear indication of the intent of the voter.”

62

Republicans wasted no time urging the U.S. Supreme Court to stay such a recount. This time, the Court acted immediately, voting five to four on the afternoon of December 9 to grant a stay and setting the morning of Monday, December 11, as a time for oral arguments on the issues. All five votes in the majority came from justices named by Reagan or Bush.

63

This was staggeringly bad news for Gore’s already discouraged supporters: There now appeared to be no way that manual recounts of undervotes, even if approved by the Court on December 11, could be completed by December 12, the date on which Florida’s certified Republican electors would be safe from congressional challenges.

One day after hearing the oral arguments, at 10:00 P.M. on the deadline date of December 12 itself, the U.S. Supreme Court delivered the predictable final blow, dispatching Court employees to deliver texts of its opinions to crowds of reporters, many of whom had been waiting in the cold on the steps of the Supreme Court building. In all, there were six separate opinions totaling sixty-five pages. To the surprise of many observers, the justices did not maintain, as many of Bush’s lawyers had expected they would, that the Florida court had overstepped its bounds by ignoring Article II of the Constitution. In the key decision,

Bush v. Gore

, the five conservative justices for the first time focused instead on the question of equal protection.

64

They stated that the recounts authorized by the Florida court violated the right of voters to have their ballots evaluated consistently and fairly, and that the recounts therefore ran afoul of the equal protection clause.

Their decision ended the fight. Bush, having been certified as the winner in Florida by 537 votes, had officially taken the state. With Florida’s 25 electoral votes, he had a total of 271 in the electoral college, one more than he needed. He was to become the forty-third president of the United States.

The next night, Gore graciously accepted the Court’s decision and conceded. But the arguments of the Supreme Court’s majority unleashed a torrent of protests, not only from Democratic loyalists but also from a great many legal analysts and law professors (most of them liberals). The conservative majority of five, they complained, had violated the basic democratic principle of one person, one vote. To achieve their ends—the election of Bush—they had uncharacteristically—and, they said, desperately—turned to the equal protection clause (normally invoked by liberals to protect the rights of minorities and other out-groups) and had ignored the Court’s own recently asserted rulings in favor of federalism and states’ rights. The majority decision had also stated, “Our consideration is limited to the present circumstances, for the problem of equal protection in election processes generally presents many complexities.” This statement meant that

Bush v. Gore

, while delivering a victory to the GOP in 2000, had no standing as precedent.

The arguments of the five conservative justices especially distressed the Court’s dissenting minority of four.

65

Justices Stephen Breyer and David Souter, while conceding that the recounting as ordered by the Florida Supreme Court presented “constitutional problems” of equal protection, said that the U.S. Supreme Court should have remanded the case to the Florida court, which could have established fair and uniform procedures for recounting. That process, they added, could be extended to December 18, the date that the electors were due to meet. The Florida court should decide whether the recounting could be completed by that time. Breyer, charging that the majority decision of his colleagues had damaged the reputation of the Court itself, wrote: “We do risk a self-inflicted wound, a wound that may harm not just the court but the nation.” Eighty-year-old Justice John Paul Stevens, who had been appointed to the Court by President Ford, added: “Although we may never know with complete certainty the identity of the winner of this year’s Presidential election, the identity of the loser is perfectly clear. It is the Nation’s confidence in the judge as an impartial guardian of the rule of law.”

66