Resolute (38 page)

Authors: Martin W. Sandler

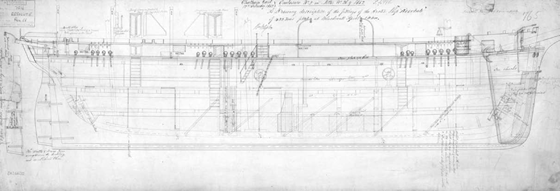

Plans of the HMS

Resolute

T

HIS RARE

B

RITISH NAVAL DRAWING

shows the side view of the HMS

Resolute

, and is titled

A Drawing descriptive of the fittings of the Arctic ship

Resolute

of 422 tons fitted at Blackwell, April 1850.

As the plan reveals, the

Resolute

was specially fitted to survive the challenges of making its way through ice floes and surviving the inevitable winters locked in the ice. This can be seen most clearly in the attention paid to reinforcing the ship's bow with “ice chocks” and with thick galvanized iron plates all “filled in between with 2-inch fir and caulked.” The plan also shows the strong “Canadian elm stringer” that ran the length of the middle of both the port and starboard sides of the vessel, and the “iron plate 5/16 thick” that also reinforced both sides of the ship.

Among other features shown in this side view are: the storage space for the “spare rudder, may be used as long or short rudder,” the “boat's skid,” the “temporary or portable hood over captain's ladder,” the “temporary or portable hood over officer's ladder,” and the “portable roundhouse.” Note how the drawing also indicates the location of the anchor and the all-important ship's bell.

T

HIS COMPANION DRAWING TO THE SIDE VIEW

on the opposite page shows the official plan of the lower deck of the

Resolute.

Indicative of the designer's and builders' awareness of the hardships the crew of the vessel was bound to face on its long voyages in the frozen North, one of the largest spaces on the ship was reserved for the sick berth. The exalted position of the captain in the British naval system is revealed by the size of the “Captain's Cabin” with its adjoining “Captain's Pantry” and “Captain's Dressing Room.” The importance of rank is also revealed by the space allotted for the private cabins of the 1st lieutenant, the ship's master, the vessel's clerk, the 2nd master, the mates, the 2nd lieutenant, the surgeon, the purser, the assistant surgeon, the boatswain, and the vessel's carpenter.

Interesting is the fact that the plan includes both a special notation stating that “the whole of the bed place have two chests of portable Drawers under them” and a detailed drawing of that staple of all naval officers and sailors, the seaman's chest. That the

Resolute

was designed and built for Arctic exploration is indicated by the drawing of the layers of wood called “Ice Chocks” fitted at the bow of the ship.

Note also the indication of the “Hot air Tunnel” along both sides of the vessel. It was this system of keeping the crewmen warm while encounterng Arctic temperatures that astounded the men of the

George Henry

when they discovered the abandoned “ghost” ship.”

Excerpt of Instruction addressed to

dated 5th May 1845,

By the Commissioners for executing the office of Lord High Admiral of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

1. Her Majesty's Government having deemed it expedient that further attempt should be made for the accomplishment of a north-west passage by sea from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean, of which passage small portion only remains to be completed, we have thought proper to appoint you to the command of the expedition to be fitted out for that service, consisting of Her Majesty's ships

“Erebus”

under your command, taking with you Her Majesty's ship

“Terror,”

her Captain (Crozier), having been placed by us under your orders, taking also with you the

“Barretto Junior”

transport, which has been directed to be put at your disposal for the purpose of carrying out portions of your provisions, clothing and other stores.

2. On putting to sea, you are to proceed, in the first place, by such a route as from the wind and weather, you may deem to be the most suitable for dispatch, to Davis' Strait, taking the transport with you to such a distance up the Strait as you may be able to proceed without impediment from ice, being careful not to risk the vessel by allowing her to beset in the iceâ¦.

4. As, however, we have thought fit to cause each ship to be fitted with a small steam-engine and a propeller, to be used only in pushing the ships through channels between masses of ice, when the wind is adverse, or in a calm, we trust the difficulty usually found in such cases will be much obviated, but as the supply of fuel to be taken in the ships is necessarily small you will use it only in cases of difficulty.

5. Lancaster Sound, and its continuation through Barrow's Strait, having been four times navigated without any impediment by Sir Edward Parry, and since frequently by whaling ships, will probably be found without any obstacles from ice or islands⦠it is hoped that the remaining portion of the passage, about 900 miles, to the Behring's Strait may also be found equally free from obstruction; and in proceeding to the westward, therefore, you will not stop to examine any openings either to the northward or southward in that Strait, but continue to push to the westward without loss of timeâ¦.

6. We direct you to this particular part of the Polar Sea as affording the best prospect of accomplishing the passage to the Pacific, in consequence of the unusual magnitude and apparently fixed state of the barrier of ice observed by the

“Hecla”

and the

“Griper”

in the year 1820, off Cape Dundas, the south-western extremity of Melville Island; and we, therefore, consider that loss of time would be incurred in renewing the attempt in that direction; but should your progress in the direction before ordered be arrested by ice of a permanent appearance, and that when passing the mouth of the Strait, between Devon and Cornwallis Islands, you had observed that it was open and clear of ice; we desire that you will duly consider, with reference to the time already consumed, as well as to the symptoms of a late or early close of the season, whether that channel might not offer a more practicable outlet from the Archipelago, and a more ready access to the open sea, where there would be neither islands nor banks to arrest and fix the floating masses of ice; and if you should have determined to winter in that neighbourhood, it will be a matter of your mature deliberation whether in the ensuing season you would proceed by the above-mentioned Strait, or whether you would persevere to the south-westward, according to the former directionsâ¦.

8. Should you be so fortunate as to accomplish a passage through Behring's Strait, you are then to proceed to the Sandwich Islands, to refit the ships and refresh the crews, and if, during your stay at such place, a safe opportunity should occur of sending one of your officers or dispatches to England by Panamaâ¦.

9. If at any period of your voyage the season shall be so far advanced as to make it unsafe to navigate the ships, and the health of your crews, the state of the ships, and all concurrent circumstances should combine to induce you to form the resolution of wintering in those regions, you are to use your best endeavours to discover a sheltered and safe harbour, where the ships may be placed in security for the winter ⦠and if you should find it expedient to resort to this measure, and you should meet with any inhabitants, either Esquimaux or Indians, near the place where you winter, you are to endeavour by every means in your power to cultivate a friendship with them, by making them presents of such articles as you may be supplied with, and which may be useful or agreeable to them; you will, however, take care not to suffer yourself to be surprized by them but use every precaution, and be constantly on your guard against any hostility: you will, by offering rewards, to be paid in such a manner as you may think best, prevail on them to carry to any of the settlements of the Hudson's Bay Company, an account of your situation and proceedings, with an urgent request that it may be forwarded to England with the utmost possible dispatch.

10. In an undertaking of this description much must be always left to the discretion of the commanding officer, and, as the objects of this Expedition have been fully explained to you, and you may have already had much experience on service of this nature, we are convinced we cannot do better than leave it to your judgement, in the event of your not making the passage this season, either to winter on the coast, with the view of following up next season any hopes or expectations which your observations this year may lead you to entertain, or to return to England to report to us the result of such observations, always recollecting our anxiety for the health, comfort and safety of yourself, your officers and men; and you will duly weigh how far the advantage of starting next season from an advanced position may be counterbalanced by what may be suffered during the winter, and by the want of such refreshment an refitting as would be afforded by your return to Englandâ¦.

19. For the purpose, not only of ascertaining the set of the currents in the Arctic Seas, but also of affording more frequent chances of hearing your progress, we desire that you frequently, after you have passed the latitude of 65 degrees north, and once every day when you shall be in an ascertained current, throw overboard a bottle or copper cylinder closely sealed, and containing a paper stating the date and position at which it is launchedâ¦.

21. In the event of any irreparable accident happening to either of the two ships, you are to cause the officers and crew of the disabled ship to be removed into the other, and with her singly to proceed in prosecution of the voyage, or return to England, according as circumstances shall appear to require ⦠Should, unfortunately, your own ship be the one disabled, you are in that case to take command of the

“Terror,”

and in the event of any fatal accident happening to yourself. Captain Crozier is hereby authorized to take command of the

“Erebus”

placing the officer of the expedition who may then be next in seniority to him in command of the

“Terror.”

Also, in the event of your own inability, by sickness or otherwise, of any period of service, to continue to carry these instructions into execution, you are to transfer them to the officer next in command to you employed on the expeditionâ¦.

22. You are, while executing the service pointed out in these instructions, to take every opportunity that may offer of acquainting our secretary, for our information, with your progress, and on your arrival in England, you are immediately to repair to this office, in order to lay before us a full account of your proceedings in the whole course of your voyage, taking care before you leave the ship to demand from the officers, petty officers, and all other persons on board, the logs and journals they may have kept, together with any drawings or charts they may have made, which are all sealed up, and you will issue similar directions to Captain Crozier and his officers. The said logs, journals or other documents to be thereafter disposed of as we may think proper to determine.

Given under our hands, this 5th day of May 1845.

(signed)Â Â Â Â

Haddington.

G. Cockburn

W.H. Gage

Sir John Franklin

, K.C.H. Captain of H.M.S.

“Erebus”

at Woolwich By command of their Lordships.

(signed)Â Â Â Â

W.A. B. Hamilton

source: (Official Report on the Franklin Expedition):

Arctic Expedition

, Ordered by the House of Commons, to be Printed 13 April 1848

CHAPTER I

The Northwest Passage.

The Spanish called it the Strait of Anian and the British termed it the Northwest Passage, but whatever it was called, the quest for a commercial route to the East occupied the hearts and minds of men for centuries. Long before John Barrow came upon the scene, pioneer explorers had experienced the adventures, the mysteries, the frustrations, the discoveries, and the tragedies that would characterize the search.

The first of these explorers was the Italian Giovanni Caboto who, in 1497, sailing for England's Henry VII under the name John Cabot, reached the northeastern coast of North America. In the first of endless misconceptions related to the search, Cabot, having heard reports of people living to the north of where he had landed, thought surely that these people must be residents of Cathay. Cabot's voyage, coupled with Vasco da Gama's discovery the next year of a sea route around Africa to India, and Ferdinand Magellan's passage around Cape Horn into the Pacific Ocean, intensified the search for a shorter route to the riches of the Orient.

In 1534, Frenchman Jacques Cartier landed on the shores of Labrador. He did not find the passage, but succeeded in penetrating as far inland as the Gulf of St. Lawrence. In 1576, the inveterate Elizabethan adventurer Martin Frobisher reached what he named Frobisher Bay on Baffin Island. Although he found no trace of a Passage, he brought back ore thought to contain gold. This discovery led to two successive larger Frobisher expeditions in 1577 and 1578, launched to mine the gold. Unfortunately, after the explorer's third voyage, the ore was found to be worthless.

Frobisher had been backed by Sir Humphrey Gilbertâa half brother of Sir Walter Raleighâand, in 1583, Gilbert undertook his own voyage, landing in Newfoundland and claiming the territory for Great Britain. Between 1585 and 1588, another English passage-seeker, John Davis, made three journeys to the Canadian Arctic where his searches took him along the coasts of Greenland, Baffin Island, and Labrador.

British attempts to find the passage continued in the early 1600s. Most notable were the voyages of Henry Hudson, Luke Foxe, and Thomas James. In 1609, Hudson sailed up the river that bears his name; in 1610, he sailed again, and discovered Hudson Bay. Later in that voyage, when his crew mutinied and he and eight others were cast adrift in a boat and never heard from again, Hudson became arguably the first of hundreds who would lose their lives in the legendary search. In 1631, rival explorers Luke Foxe and Thomas James made their attempts. Foxe explored the western shore of Hudson Bay and Baffin Island while James reached Hudson Bay's southern shores. Although neither man would suffer as tragic a fate as Hudson, Foxe was forced back to England by scurvy and James had to endure an almost disastrous winter trappedon Charlton Island.

While almost all these voyages produced new discoveries, not one even approached achieving the sought-after prize. Enthusiasm for the search waned even further when reports of some of the adventurers' experiences were published. “It would be sometimes so extreme that it was not endurable,” James wrote of the life-threatening temperatures he had encountered, “no clothes were proof against it; no motion could resist it. It would, moreover, so freeze our eyelids that we could not see; and I verily believe that it would have stifled a man in a very few hours.” Thanks to such reports, no other serious attempts to find the passage were made for almost one hundred years.

In 1774, however, the English parliament, anxious to outdo rival nations by finding a more profitable route to the East, rekindled enthusiasm for the search by offering a £20,000 reward to anyone who found it. But tragedies continued. In 1776, James Cook, at the time acknowledged as the world's most accomplished navigator, tried his hand. He reached the Bering Strait by sailing up the West Coast but had to turn back when the waters ahead of him were completely blocked by ice. Later in the same long voyage, Cook would lie dead on a Hawaiian beach, fatally clubbed and stabbed by natives.

All of these quests were but a prelude to the seemingly endless succession of nineteenth-century searches initially promoted and launched by John Barrow, quests which, before the century was three-quarters over, would make the trials and consequences of the earlier searches seem mild in comparison.

William Baffin.

Early British explorer William Baffin (1584-1622) was pilot on two passage-seeking expeditions sent out by a company boldly calling itself the Company of Merchants of London, Discoverers of the North West Passage. On his first voyage in 1615, in which the expedition vainly attempted to find a channel in Hudson Bay, Baffin deduced the first longitude ever calculated at sea. A year later, passing up Davis Strait, his second search resulted in the exploration of what was called Baffin Bay and the northeast shore of what Edward Parry later named Baffin Island “out of respect to the memory of that able and enterprising navigator.” Despite its discoverer's claim, the existence of Baffin Bay was long discredited, perhaps because, after two unsuccessful attempts, Baffin was vocal in expressing his belief that there was no Northwest Passage, a proclamation that discouraged many would-be explorers from Arctic exploration.

Even though John Ross's life would be filled with future Arctic adventures, some of them never equaled, the ridicule that he received because of his mirage-inspired abandonment of John Barrow's first attempt to find the passage would follow him for the rest of his days. But his confirmation of William Baffin's discovery of a body of water that would prove vital in the Arctic quest was a major achievement.

Samuel Hearne.

John Franklin was not the first to make an overland journey through the Canadian Arctic. Fifty years earlier, British explorer and fur trader Samuel Hearne made three arduous treks through the unexplored territory and, in the process, discovered many of the places that formed the backdrop of the Franklin expedition.

Born in London in 1745, Hearne entered the British navy when he was only eleven years old and took part in several battles of the Seven Years War. In 1766 he was hired by the Hudson's Bay Company and served aboard two of the Company's ships. The desire to explore was in his blood and when informed of native reports of a great river and large copper mines that lay in the Canadian wilderness, he volunteered to lead an expedition to discover them. In the annals of all the British expeditions that would follow, his experiences in the Arctic were unique. No other explorer would ever be asked to entrust his life so completely to the natives as Samuel Hearne.

In 1769, Hearne, accompanied by two Company employees and a group of Chipewyan Indians, set out to find the river and the mines. From the beginning, Hearne underestimated the magnitude of the task he had undertaken. Like all other white men, he had no idea of the expanse of the Canadian wilderness or the severity of its climate. After traveling two hundred miles and continually facing death by starvation or exposure, the Chipewyan pleaded with Hearne to return with them to the fort from which they had started. When he refused, all of the Indians, save one, abandoned him and Hearne's first expedition came to an ignoble end.

A year later he was at it again. This time he was better equipped and had a larger band of Chipewyans with him. Once again, coping with the weather and finding enough food were major challenges, but by sheer determination Hearne penetrated deeper into the American subarctic than any other white man and drew the first maps of the interior of northern Canada ever made. Despite the severe conditions, he daily grew more confident of success. But it was not to be. Having left a temporary campsite for a day's hunting, Hearne returned to find that a newly arrived band of Indians had run off with his quadrant and other gear. Hearne and two Chipewyans tracked them down and recovered the items, but it was a temporary reprieve. Shortly afterwards, when Hearne had mounted his quadrant on a rock to take a reading, a huge gust of wind blew the vital instrument over, smashing it beyond repair. With no means of verifying positions or determining distances, Hearne was once again forced to stop short of his goal. Again he would not admit defeat. Encouraged by the progress he had made on his second journey, the Hudson's Bay Company agreed to finance yet another attempt, this time supplying Hearne with as many supplies as heâand an even larger contingent of Chipewyansâcould carry.

Hearne's third expedition set out in December 1770. Despite being better supplied, his long trek would still require his party to continually hunt and fish for food. Several times the weather turned so bad that even Hearne considered turning back. But he made himself go on and became the first white man ever to cross the enormous open tundra that became known as the Barren Grounds. Along the way he discovered and named a number of lakes and other landmarks. Then he found Great Slave Lakeâso-named after the native Slavey tribe, who lived in the areaâand beyond it the goal itself. Standing on the banks of what would be called the Coppermine River, he noted in his journal: “We have finally arrived at the long wished-for spot.”

Hearne's triumph would be followed by one of the worst experiences of his life. Just days after he had discovered the Coppermine, his party came across an Inuit settlement. The Chipewyans, bitter enemies of the Inuit, attacked the settlement in the dead of night and brutally massacred twenty men, women, and children in their sleep. The site would become knownas Bloody Falls, the same spot where fifty years later, Franklin's Indians wouldabandon him.

Hearne had been helpless to stop the massacre and years later would note in his journal that he still wept over the memories of what he had witnessed. But now he stood at the Coppermine. Canoeing northward along it, he navigated its 525 miles, charting it along the way, and reached its mouth at the Arctic Ocean. He was still not done. Traveling back along the river, he found the copper deposits. But they were a disappointment. As far as he could determine, they were nowhere near as rich as they had been rumored to be.

Nonetheless, Hearne had accomplished what he had set out to do. He had discovered and mapped the Coppermine River and had traced it to the Arctic Ocean. He would remain in the North for the next fifteen years where, among other accomplishments, he would establish Cumberland House, the Hudson Bay's first interior trading post, a place which, half a century later, would provide a lifesaving haven for John Franklin and his men.

Scurvy.

Caused by a lack of vitamin C, scurvy first emerged as a problem for maritime explorers when they began to make extended voyages into the Pacific and Indian Oceans. In 1499, while sailing to India, Vasco da Gama lost two-thirds of his crew to the disease. Twenty years later, more than 80 percent of Ferdinand Magellan's men died from scurvy while crossing the Pacific. A British report, issued in 1600, estimated that in the previous twenty years, some ten thousand mariners had been killed by what adventurer Sir Richard Hawkins called the “plague of the sea” and the “Spoyle of Mariners.”

By the early 1800s, scurvy had become so pernicious and widespread that, at times, as much as one-third of the Royal Navy was incapacitated by it. The problem was that no one knew what caused it. Its symptomsâincluding malaise, lethargy, shortness of breath, and, in the later stages, fever, convulsions, and emotional disturbancesâwere so varied that it was commonly mistaken for syphilis, dysentery asthma, or even madness.

Actually, the first breakthrough in determining both the cause and the means of preventing scurvy took place as early as 1747, when the British naval doctor James Lind conducted an experiment on six pairs of sailors who were seriously afflicted with the disease. Lind fed each of five of the pairs a different “cure”âcider, vinegar, distilled sulfuric acid, garlic-mustard paste, and seawater. None had any effect. But the sixth pair of seamen, who had been fed two oranges and a lemon every day, recovered completely within a week. Despite this discovery by one of its own physicians, however, it took the Royal Navy some fifty years before it began regularly supplying its vessels with lemon juice as a preventative against the disease. (The fact that the British commonly referred to lemons as “limes,” coupled with the use of lime juice as well as lemon juice, led to the emergence of the nickname “limey” for British sailors).

More than the British Admiralty ever realized, the nineteenth-century Arctic expeditions were particularly susceptible to scurvy. Unlike their whaling counterparts, whose global pursuit of the migratory whales most often enabled them to put into ports to take on fresh vegetables and meat, the passage-seekers, ensconced in northern waters for years at a time, had no such opportunity. And even those commanders who were wise enough to store lemon or lime juice aboard their vessels had no way of knowing that vitamin C loses its potency over time, thus making it less effective during the long polar explorations. Seriously compounding the problem was the fact that many of the commanders, particularly when forced to winter in the ice, mistakenly instituted antiscurvy practices that, instead of preventing or alleviating the disease, actually caused or hastened its progression. Edward Parry was typical of scores of well-intentioned commanders when he regularly doled out rations of beer and instituted a strict regimen of exercise aboard his ship. It would not be until a century later that it would be discovered that both practices caused a hastening of the disease. Ignorance of ways to prevent scurvy was, in fact, so widespread that John Ross was actually criticized for copying the Inuit by feeding his men a regular diet of vitamin C-rich fresh salmon whenever he could during the four winters between 1829 and 1833 that his ships were iceboundâthis, despite the fact that when he finally was able to return to England, his entire contingent was relatively scurvy-free.