Reporting Under Fire (6 page)

Read Reporting Under Fire Online

Authors: Kerrie Logan Hollihan

Mr. Kirtland is a Yale graduate, class of 1903, and he and his bride will spend the winter in France.

If ever there were an understated mention of a honeymoon destination, it was in that wedding announcement. Helen and Lucien's “winter in France” was in truth a working honeymoon. Staff correspondents for

Leslie's Illustrated Weekly

magazine, Helen and Lucien were off to France to cover the war. As a man, Lucien had no trouble gaining credentials that gave him access to the front lines in France, but for Helen, the same rules didn't apply. The only American women in France were nurses, YMCA canteen workers and entertainers, and the special group of “Hello Girls” who worked as telephone operators at American headquarters. Not one woman was a credentialed war correspondent in the fall of 1917.

That didn't stop Helen. She wangled access to the front by somehow getting herself associated with the YMCA. That task accomplished and camera equipment in hand, she tramped all over France and Italy with her new husband.

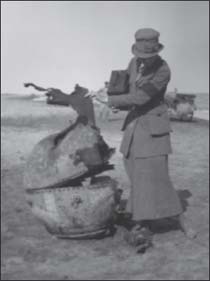

Photographer Helen Johns Kirtland posed with an exploded marine mine on the Belgian coast during World War I.

Library of Congress LC-DIG-ppmsca-32779

No newcomer to European life, Helen was a veteran traveler when she accompanied Lucien to France. Her father, Henry Johns, was a self-made man who invented and patented fireproof roofing shingles, getting his start in the basement of a New York tenement home where he experimented with his idea by pouring hot tar over old sheets and running them through a washing machine ringer.

Henry Johns died in 1898 of lung disease unwittingly brought on by the asbestos he used to make his products fireproof. Helen's mother Emily moved her two daughters to Bronxville, New York, a thriving art colony and home to writers, painters, and architects, and Helen grew up appreciating the visual arts. Her mother toured Europe with her girls, and decorative postcards they sent back and forth mentioned they were using cameras to “try some photos.”

It's not clear how Helen Warner Johns met Lucien Kirtland, but they may have first crossed paths while working for

Leslie's

magazine. When the couple first arrived in France in the fall of 1917, most American forces will still in training and just beginning to arrive in Paris, just in time to relieve the exhausted

French and British armies who had been fighting Germany for three long years.

Helen's photographs showed her skill with the big box camera that she took everywhere. She shot memorable images of the bombed-out city of Verdun, France, from a ruined window in a cathedral, Italian soldiers on the march, and French women cutting and sewing the linen to cover the skeletons of rebuilt Liberty planes.

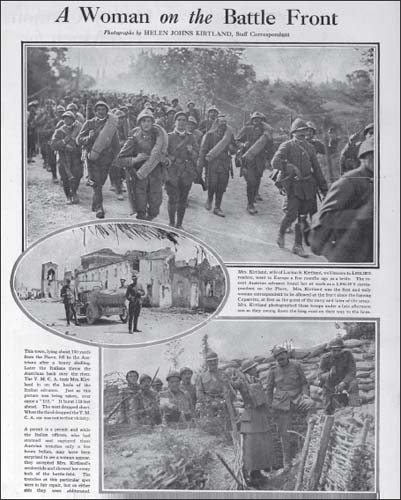

One of the

Leslie's

articles stated that Helen was the only woman permitted at the Italian Front after the disastrous Battle of Caporetto, with 10,000 soldiers killed, 20,000 wounded, and 275,000 made captive by their Austrian enemies. Helen and Lucien also recorded the famed day of June 28, 1919, when the Treaty of Versailles was signed in France and brought peaceâfor a timeâto Europe. But there was still the grinding, dangerous task of clearing the countryside of unexploded armaments. Helen's vivid description arrived on a postcard she sent to her mother:

I am first beginning to get over the queer sensation of crossing the lines & wandering in no man's land, even yet one hears tremendous explosions now & thenâ& these only add local colorâAppropriate sounds to describe the sights! For they are of course cleaning up the country of duds as systematically as they canâMy! What a job!! I'd hate to be a farmer in these parts! ⦠Every now & again someone gets “Bumped off.”

The shells & their little brothers the hand grenades, are not a race of savages to get too chummy with & stub your toe on one as you tramp thru the pits & hummocks among the linesâmay meanâyou won't finish the day's program. I am quite well trainedâin fact I guess most of us who have been here during the war when the air was

alive with them, are & no souvenir hunting is worth risking the consequences of touching these steel fiends that may not be dead but only sleeping!

Leslie's Illustrated Weekly Newspaper

credited Helen Johns Kirtland with photos she took at the Italian Front.

Library of Congress, LC-DIG-ppmsca-07628

The beaches too will have to undergo a spring cleaning to be ready for children & their sand pails & shovels for they are chuck-full of barbed wireâ& mines lie in half dozens unexploded & menacing; some nearly buried in drifts trying to sink into oblivionâto forget their era & wicked lifeâothers standing quite on tiptoe & ready to fightâ& when the wind blew sand around their “horns” I imagined I could see smoke, warning us that given occasion, or un-careful treatment, this round, fat dragon would belch forth more than smokeâfire, sharp steel, & destruction. One doesn't turn these things over on their backs to see the other side!

After the war Helen and Lucien Kirtland traveled the globe as Lucien wrote for a number of American magazines and penned two books about Asia. Helen apparently worked in tandem with Lucien taking pictures to accompany his articles, but her name rarely appeared in credits. In one issue of

Leslie's Photographic Review of the Great War,

however, she penciled in her initials, H.J.K., next to an uncredited photo that apparently was hers.

The Kirtlands collected scores of art objects in their travels, many of which were sold by an exclusive auction house after Helen died in 1979. The couple had no children. The Library of Congress holds a large collection of their photos, donated by a family associate. Historians hope to dig deeper into Helen's life, but the Kirtlands' books, letters, and other papers seem to have disappeared without a trace.

Between World Wars 1920â1939

W

ith the armistice signed, Americans sailed home in 1919. They were greeted by a shaky economy, joblessness, and a gripping fear of communism in Russia and whether American workers would rise up in revolution. Shipyard strikes, steelworkers' riots, hints of Bolshevik teachings at colleges, and random bombings terrorized Americans. For a year this Red Scare dominated the headlines.

Americans, weary of foreign entanglements, yearned to settle back and forget the world's problems. In a landslide election in 1920, they sent Republican candidate Warren G. Harding to the White House. Harding promised a return to “normalcy,” and back to normalcy Americans went. Armed with a tool called “credit,” they spent their way into a booming economy. The good times rolled, and the stock market climbed ever higher.

So did hems on ladies' skirts. Trendy young women bound their breasts to fit into straight-up-and-down chemises. The bolder ones smoked in public, and the boldest chose to have sex outside of marriage.

Dailies and magazines still provided Americans with most of their news, and in 1920, KDKA in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, made radio's first commercial broadcast to announce that Harding had won the election. When people went to the movies, they viewed black-and-white newsreels with news from home and overseas.

Women continued working as journalists, but the social changes after World War I, including the right to vote, didn't change their status on newspaper staffs. Editors continued to assign their “girl reporters” to the “woman's angle,” even at the new English-language papers in Europe. But that didn't stop young women with a nose for news from heading overseas.

London, Paris, and Berlin played host to American news agencies, and these young women, armed with college degrees, a bit of cash, and adventurous spirits, freelanced for the International News Service (INS), Associated Press (AP), and United Press (now known as UPI, United Press International). Placing one's articles with this or that wire service was a surefire way to get noticed and, with luck, find a paying job. Paris especially drew young Americans with a taste for adventure. Artists, musicians, poets, authors, booksellers, and newspaper reporters flocked to the City of Light. Rents were low, and wine was cheap.

From Indianapolis, Indiana, by way of New York came Janet Flanner, an aspiring poet and novelist who divorced her husband and embarked with her lover, Solita Solano, to Paris. Flanner, taking the pen name Genêt (which sounded like her first name), tantalized readers of the

New Yorker

magazine with

French gossip and tales of bohemian life. Anne O'Hare McCormick pitched stories to the

New York Times

and scored a telling interview with the young fascist Benito Mussolini when others ignored him.

Peggy Hull, fresh from months covering the Russian Revolution, moved to Paris and made a new friend in Irene Corbally, a girl from Greenwich Village, New York, who worked for the

Chicago Tribune.

Dorothy Thompson, a minister's daughter, got tired of her tame existence as a paid reformer and publicist and sailed to London in search of a newspaper job.

Hull and Corbally ended up circling the globe to work in China, while Thompson aimed her sights at the German-speaking nations. Another American reporter, the German-speaking Sigrid Schultz, was working in Berlin when Thompson first arrived.

Hull, Kuhn, Thompson, and Schultz were expected to write stories catering to female readers. However, they wrote what they saw, convinced that the United States could never maintain its isolationism, and they sent early warning signals about murderous governments in Germany and Asia that would drag Americans into World War II.

After the fall of China's Qing Dynasty in 1911 there were hopes that a Chinese republic would replace it with the support of China's Nationalist Party. However, the notion of democracy in China failed as China's generals and warlords competed for power and built their own fiefdoms across the land. For China's millions of peasants, life didn't change; they continued to work the earth by hand as they had for centuries. In China's isolated cities, the poor lived in wretched conditions, many of them in

the streets. There was next to no indoor plumbing or sewage treatment; human excrement was removed by laborers. (Westerners called them “night soil coolies.” “Coolie” was a term for a person who did manual labor). Diseases such as cholera ran rampant. Beggars were a common sight. Women had no rights; frequently poor girls were sold by their families when they couldn't feed them. No national form of education existed, and just a handful of Chinese children went to school, often run by Christian missionaries.

But change was coming. The rise of a New Culture Movement offered elite young men university educations that exposed them to Western ideas such as the concept of democracy and the scientific method. The Soviet Union also sent advisors to assist the Nationalist Party and its leader Sun Yat-sen. For a time, the Nationalists joined forces with China's Communist Party, hoping to establish a republic across China.

In 1925 Sun Yat-sen died unexpectedly. His military commander, Chiang Kai-shek, took control of the Nationalists and marched north and successfully attacked several enemy warlords. Then in 1927, Chiang reversed course and attacked the Communists in his own party, murdering hundreds of Shanghai workers who had joined the Communists. In 1928 Chiang's army swept into China's capital, Beijing, consolidating power across China for the first time in 12 years. However, the Communist Party held on in widespread pockets across central and southern China. In 1934 Chiang's armies began to force the Communists out in a massive retreat known as the Long March during which hundreds of thousands of Communists died. Out of this debacle rose a new Communist leader, Mao Tse-tung (Mao Zedong) and his bright-minded associate Chou En-Lai.

REPORTING FROM SHANGHAI

Turn the calendar back, give me another chance, and I'd do it all over again; nor would I take a million dollars cold for the experience. I wouldn't give up one heartache or trade any part of the agony or high adventure for a chance to live my life again in security and peace. To live close to reality is really to live.