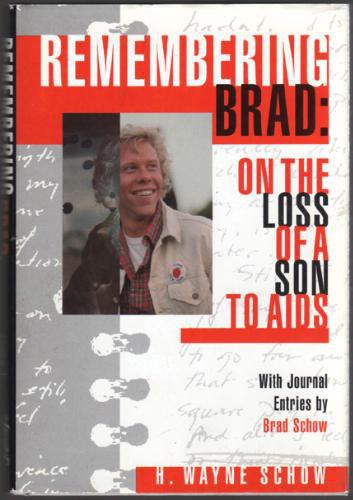

Remembering Brad: On the Loss of a Son to AIDS

Read Remembering Brad: On the Loss of a Son to AIDS Online

Authors: Wayne Schow; Brad Schow

Remembering Brad

On the Loss of a Son to AIDS

H. Wayne Schow

on the cover:

“How can I begin to relate the powerful emotions I felt while reading

Remembering Brad?

I especially appreciate the author’s combination of the sacred and secular, the emotional and intellectual. I, too, will remember Brad.”

—Barbara J. Shaw, Executive Director, Utah AIDS Foundation

“This important book needs to be read twice: the first time slowly, savoring the powerful feelings and profound growth, then a second time aloud to as large an audience as you can find.”—Gerry Johnston, mother of a gay son; founder, People Who Care

“Remembering Brad caused me to recall my own struggle to reconcile my sexual orientation with my spirituality. More importantly, Schow relates the coming out process for parents, offering significant assistance for families trying to understand and accept.” —Duane Jennings, Director, Wasatch Chapter, Affirmation: Gay & Lesbian Mormons

jacket flap

In the terms of cultural geography, it’s a long way from Los Angeles to Pocatello. This is the story of a young man who lived in West Hollywood, then returned to the Idaho environment in which he was born and raised—ironically to die of AIDS. It is unfortunately a story that is no longer uncommon.

Brad’s temperament challenged the scenarios normally planned for young men in rural America. His ambivalent views regarding his sexual orientation are evident in his diary. “I’ve been in one of my anti-homosexual moods again today,” he wrote. “Raging inside myself against the horrible anti-social sexual werewolves that we all are. Right? Like I said–what’s a boy to do? I have to confess, I don’t understand the whole thing.”

In writing about his son, H. Wayne Schow reveals his own journey of sorting things out. This is a biography not only of Brad but also of those whose lives he touched and a memorial to all like him who have felt ostracized, marginalized, or alone.

“I’m going to die soon,” Brad wrote on 5 September 1986. “Nothing to do about it. I miss Genesee Street in L.A. That was a cosmic point for me. It goes with me in my heart. I can’t describe it. Scott would know.”

About the author:

H. Wayne Schow

, whose son Brad died of AIDS in 1986, is co-editor of

Peculiar People: Mormons and Same-Sex Orientation.

His published essays include “Homosexuality, Mormon Doctrine, and Christianity” in

Sunstone

magazine. A Professor of English at Idaho State University, Schow also chairs the Department of English and Philosophy. His professional publications include a volume of translations,

Against the Wind: Stories by Martin A. Hansen,

and critiques of such writers as Isak Dinesen, Gűnter Grass, Joan Didion, and Ford Madox Ford. Schow lives in Pocatello, Idaho, with his wife Sandra. They are the parents of four sons.

Printed in the United States of America by Signature Books.

Signature Books is a registered trademark of Signature Books, Inc.

Dust jacket design by Clarkson Creative

For Sandra who walked this road with me.

Prologue

The mind is an instrument for arranging the

world in accordance with its own needs and desires.

[Hence] its arrangements must be fictive.

—Frank Kermode

It’s a long way from New York or Los Angeles to Pocatello, Idaho. The distance is not measured simply in miles. Here in this provincial place, in the mountains on the edge of the Snake River Plain, life seems less pressured, less complicated.

The distance and difference is partly a matter of pace. We don’t really have a fast lane in Pocatello. What doesn’t happen today can wait for tomorrow. And the distance is partly a matter of elbow room. There aren’t so many of us compressed together here. Perhaps that is why our crime rates are low, racial tensions are barely discernible, and you can walk clean streets in any part of town safely, day or night. When you do feel the urge to get out of town, scenic Idaho is immediately all around you, open and accessible. The sun shines brightly, the air is clear, and you can see the Lost River Range rising above the desert seventy miles away.

Our distance from the cosmopolitan places is partly too a matter of style. We don’t set trends here, we don’t dictate fashion. You don’t see evidence of great wealth. We’re probably not on the cutting edge of anything. Our style and values are more those of middle America. Most of us know and like our neighbors; most of us live conventionally, predictably; most of us avoid tension-producing extremes.

For these reasons, Pocatello is a comfortable place. Here you feel largely sheltered from the ills that beset contemporary urban life. Here you generally expect life to be kind.

In this sunny environment, where he had grown to manhood, my oldest son Brad died of AIDS. That was not kind. Somehow it still seems to me, eight years later, not the sort of thing that should have happened in southern Idaho. The cultural geography is altogether wrong.

That sounds terribly naive, I know. For, of course, taboo sexual orientation and taboo illness and untimely death occur everywhere, including sheltered uncosmopolitan places. But they aren’t always acknowledged. Somehow we pretend they aren’t there. My story of the brief life of a gay son and the response of his Pocatello family is different in some respects from what it would have been had it occurred in New York or San Francisco, for it takes place in a conservatively backlit context of denial.

And that is precisely why I think this story should be told. Though it seems anomalous the wrong events in the wrong place I know now what I did not know eight years ago, that this is a common story, lived by other homosexuals and their families in middle American places like Pocatello, a story unfortunately suppressed because of culturally induced shame and fear. As a result, those who dare not express their pain in the face of society’s intolerance suffer in closeted silence, and the world goes on thinking that such things occur only in the far off environments of New York and San Francisco.

This book is about Brad, whose temperamental complexity stretched the scenarios normally planned for young Mormons. In writing about him, and by that means attempting to understand his complexity, I have come to realize that this book is also about me, and about the process of sorting things out. The years continue to pass, yet I cannot be done with thinking of him and the impact of his life on mine. In a manner I would never have predicted, he became and continues to be my teacher. That is a paradox worth exploring.

The miscellany that is collected here evolved piecemeal, without initially any intent of its being made into a book. I lost a son in 1986, and I had to try to make sense out of that absurdity. I wrote for therapeutic reasons. Over a period of several years, I took up new facets of this involved narrative as the necessary perspectives dawned on me, without giving much thought as I went along to what I had written earlier.

My first response was a long letter to a Mormon apostle in early 1987, subsequently revised and published as an essay in Sunstone magazine in February 1990 and reprinted in Peculiar People: Mormons and Same-sex Orientation the next year. Written shortly after Brad’s death, it grew out of my conviction at the time that matters need not have turned out for him as they did. If external conditions had been otherwise, if the theological, institutional, and social causes of his impasse could have been identified and “fixed,” then he would not have needed to suffer. That first piece of writing was a reflex action on my part, in retrospect noteworthy for its good intentions and naiveté.

A year or so later, as my hope for external fixes waned, a lamentation (the first essay in this collection) emerged from a more fully acknowledged existential mood. The essay on grief followed, and about that time I realized that if my intent was to present Brad’s story to others, he could tell parts of it far more insightfully than I. Hence, the decision to incorporate selections from his journals. Having by this time come at these events from several perspectives, I recognized that Brad’s life could be seen as a search for a spiritual standing place and that, in a less dramatic way, was true of my life as well. The personal ambivalence I felt pursuing that search within a spiritual community, and that I am sure Brad felt even more intensely, found allegorical expression in “The Great Western Cooperative,” included here as an epilogue.

There is some degree of repetition in these selections. I hope the reader will understand it as resulting from my compelling need to sift and resift these experiences in order to puzzle out their nuances. And corollary thereto, such repetitions reveal that the book as a whole has not an entirely consistent point of view, since my attitudes changed as time passed. The man who wrote the letter in 1987 is not the same one who a year later wrote the essay on tragedy. And so on. The same is true of Brad’s journal entries, which are shot through with contradictions. I have not attempted to remove these inconsistencies, for they illustrate the complex and problematic reality of my life, and of Brad’s, during this period, indeed of human lives generally.

Experiences of the kind treated here are not permanently fixed as they occur. The meanings will not hold still because we cannot (or will not) hold still in response to them. Not only do new, subsequent experiences change us from what we were, the past itself changes as well because, ourselves altered, we see it differently. Its truth cannot be detached from our perception. In our continuing assessment of it, we attach additional significance to some features and de-emphasize the significance of others. In this way I have come to realize that we create our fictions, which is an important outcome for me in the sorting-out process this book describes.

Chapter 1

On Tragedy and the Death of a Son [July 1988]

So quick bright things come to confusion.

—

A Midsummer Night’s Dream

In common speech the word “tragedy” has become roughly synonymous with personal misfortune, especially if life has been lost. A father of a young family is killed in an automobile accident, a beautiful child dies of a blood disease, an airliner smashes into a mountain carrying a hundred people to their deaths: such occurrences are pronounced tragedies, especially by those who knew the victims.

But in a stricter sense the tragic vision of life embodies more than simply misfortune and loss, more than victimization and pathos. Works such as Sophocles’

Oedipus the King

, Shakespeare’s

Othello

, and Goethe’s

Faust

impress on us a paradox, that tragedy has a powerful affirmative side. Misfortune notwithstanding, tragic vision ultimately makes us aware of impressive dimensions in human nature. Instead of plunging us into despair at the prospect of life’s cruel uncertainties, tragedy in the strict sense reconciles us to existence because it makes us believe that we can be greater than our fall.

The essence of tragedy may be understood by examining the nature of the world in which it happens and the nature of the individual who is centrally involved. The protagonist’s downfall occurs in part because he is subject to powerful external forces inimical to his needs and desires. Or, as one critic expresses it, “tragedy explores thwarted energy and possibility.”

Yet the catastrophe that overwhelms the central figure is seldom simply a matter of externalities impinging on his life. Aristotle wrote that such a one is not perfect but has a “flaw.” Accordingly, he bears some responsibility for his fall. For example, his impasse may derive from powerful internal contradictions. Or his flaw may be just that he refuses to accommodate external demands. Although by conforming to them he might well avoid catastrophe, he refuses to compromise. Where most of us would retreat from confrontation, his flaw may be just that he insists on his dignity, his pride, his sense of what he justly desires though it means that he must suffer ruin as a consequence.