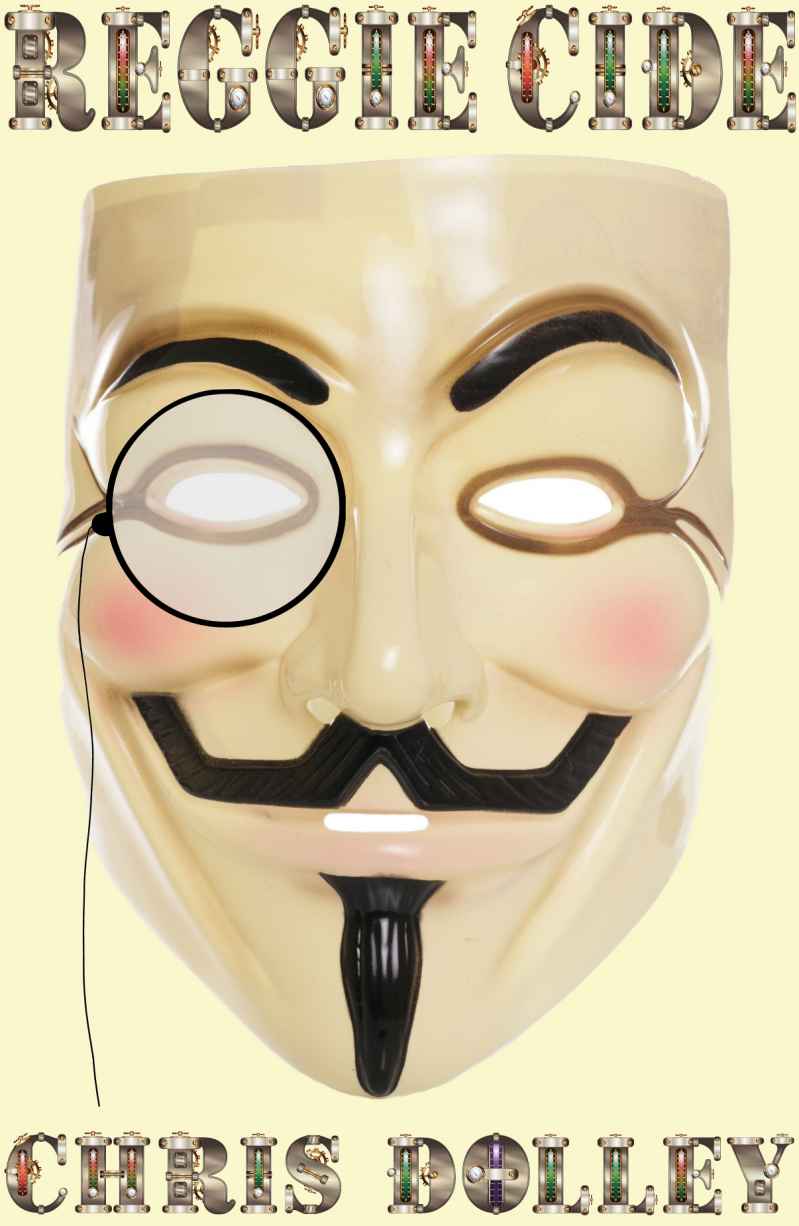

Reggiecide (Reeves & Worcester Steampunk Mysteries)

Read Reggiecide (Reeves & Worcester Steampunk Mysteries) Online

Authors: Chris Dolley

Tags: #Jeeves, #Guy Fawkes, #steampunk, #Edwardian, #Victorian, #Wodehouse, #Sherlock, #humor, #suffragettes, #Reeves

_______________

Copyright © 2012 by Chris Dolley

All Rights Reserved, including the right to reproduce this book or portions thereof in any form.

Published by Book View Café

ISBN: 978-1-61138-207-5

Cover art © Chris Brignell - Fotolia.com

Steampunk Font © Illustrator Georgie - Fotolia.com

Cover design by Chris Dolley

This book is a work of fiction. All characters, mad scientists, locations, and events portrayed in this book are fictional or used in an imaginary manner to entertain, and any resemblance to any real people, situations, or incidents is purely coincidental.

Thank you to my editors: Jennifer Stevenson and Sherwood Smith.

And, of course, Pelham Grenville Wodehouse.

t is a truth universally acknowledged that a chap in possession of a suffragette fiancée is in need of a pair of bolt cutters.

t is a truth universally acknowledged that a chap in possession of a suffragette fiancée is in need of a pair of bolt cutters.

“Which railing is she chained to now, Reeves?”

“The Houses of Parliament’s, sir. Miss Emmeline and five other ladies are protesting in Parliament Square.”

“Have the police been summoned?”

“I fear their arrival is imminent, sir. Shall I fetch your driving coat?”

I positively shot out of the door. Reginald Worcester does not dawdle when a damsel is about to be distressed by the long arm of the law. Especially when said damsel happened to be Emmeline Dreadnought who, like Queen Elizabeth when confronted by the Spanish Armada, would not go quietly. And there was nothing that irked a magistrate more than a person who would not go quietly. She could get fourteen days!

I pushed the Stanley Steamer to its limits, turning into Piccadilly on two wheels.

“How’s the brain, Reeves? Up to pressure and full of vim?”

“It appears to be functioning within acceptable parameters, sir.”

Reeves’s steam-powered brain was one of the Seven Wonders of the Victorian World. If anyone could save Emmeline from fourteen days of embroidering mail sacks, Reeves was the chap.

“Can you see her?” I asked as we swung into Parliament Square.

“I believe,” said Reeves, holding onto his bowler with one hand and the side of the Stanley with the other, “that that is Miss Emmeline by the main gate, sir. It does not appear that the constabulary have arrived yet.”

I swerved the car towards the small outcrop of humanity clustered around Parliament Gate. Emmeline was on the far right of a line of six ladies. I don’t know if there’s a dress code for protesting, but these ladies would not have looked out of place in the Royal enclosure at Ascot — except for the placards and chains. The Ascot stewards take a dim view of both.

“Votes for women!” they chanted in unison, waving placards conveying a similar message.

Emancipation Now! Votes For Ladies!

A small group of onlookers had stopped to watch the protest. I aimed the car to the right of them and pulled hard on the brake lever. The Stanley stuttered to a complaining halt a few yards short of Emmeline.

“Good morning, ladies,” I said, rising from my seat and doffing the old driving cap. “Sorry to interrupt and all that but ... Emmeline! Quick, jump aboard. The rozzers will be here any second!”

“Good,” said Emmeline, affecting a surprisingly haughty tone. “Let them come. Votes for women!”

“What?”

I climbed down from the Stanley and attempted to reason with the young firebrand.

“I don’t think you quite understand, Emmeline. The police take a dim view of the Queen’s peace being disturbed. Especially when it involves people chaining themselves to the Palace of Westminster’s wrought ironwork! You’ll go to

prison

.”

“Perhaps I want to go to prison. Votes for women!”

“No one

wants

to go prison. It’s much over-rated. They don’t serve tea until well after six and there are positively

no

cocktails. Come on, Reeves. Cut those chains.”

“Reeves!” commanded Emmeline. “Stay where you are!”

“If you wish, miss, though ... might I suggest you reconsider your current plan of action?”

“Don’t listen to him, Emmeline. He’s a man,” said one of Emmeline’s sisters-in-chains. I’m not sure if Valkyries had aunts, but if they did — and they were partial to large hats and ostrich feathers — this woman could have been a stand-in for Brunhilde’s on her days off.

“Actually, he’s not a man,” I countered. “He’s an automaton. A dashed brainy one at that. And if Reeves says reconsider, I’d jolly well listen to him.”

Emmeline would have none of it. “This is not a time for listening, Reggie. This is a time for action.”

Reeves coughed, one of his mildly disapproving coughs. He’d aired it earlier upon discovering a pair of duck egg blue spats I’d hidden at the back of my wardrobe. “Would not your arrest, and subsequent incarceration, miss, severely limit your ability to protest?” he said. “If you accompany us now, you can protest again tomorrow but, if you are imprisoned, you will be unable to demonstrate for fourteen days.”

“Fourteen days of hard embroidery,” I added.

“Ah, but I’ll have my day in court,” said Emmeline. “It’s time we took our fight to the judiciary and showed them that women will no longer put up with injustice. Votes for women!”

Four contralto voices echoed Emmeline’s call.

This was not going well.

“Why don’t you take my vote, Emmy? I never use it.”

“That’s very sweet of you, Reggie, but I should have a vote of my own. All women should. It’s outrageous that it’s Nineteen Hundred and Three and women

still

don’t have the vote.”

“I think you’ll find that most aunts have had their husbands’ vote for years. I know Aunt Bertha has. I’m pretty sure she has the gardener’s too. One glare from Aunt B and one toes the party line.”

“I say,” boomed a male voice from somewhere to my right. “Aren’t you Reginald Worcester, the gentleman’s consulting detective?”

I didn’t recognise the chap. He looked like a taller and less menacing version of my old house master at Melbury Regis — Stinker Stonehouse, a man who viewed the protection of the school larder from the nocturnal predations of small boys as the highest possible calling.

“Well this

is

a rare piece of luck,” said the newcomer. “Scrottleton-Ffoukes is the name. I’ve mislaid a relative and I need to get him back pretty smartish.”

“Have you looked in all the usual places?” I asked.

Reeves coughed, not one of the disapproving genus this time, more of the ‘I have an observation to make, sir, but am far too well-mannered a valet to interrupt’ variety.

“I’m afraid in this case,” said Mr Scrottleton-Ffoukes, a man obviously unfamiliar with Reeves’s oesophageal lexicon. “That there

are

no usual places. I had wondered if I might find him here, but am rather relieved I have not. I say, could we go somewhere private? This is a most unusual and delicate matter.”

Reeves coughed again.

“You have an observation, Reeves?” I asked.

“Only that this appears to be a most interesting case, sir, and what a pity it is that Miss Emmeline is otherwise engaged.”

Reeves had done it again! The man must bathe in fish oil. His brain was positively turbot-charged.

“Indeed,” I said, catching Emmeline’s eye. “Are you sure you won’t reconsider? I know how much you love a good mystery.”