Rebuild the Dream (21 page)

Authors: Van Jones

Because witnessing certain processes will turn one's stomach, there are two things that one should never see while they are being made: sausage and laws. The Inside Game is where the political sausage-making happens. As unpleasant as this dimension of politics

is, any cause or candidate that does not find an effective way to relate to the reality of the Inside Game will likely fail. At best, such crusades will be consigned to the margins of American life for a very long time.

THE POLITICAL PROCESS REQUIRES

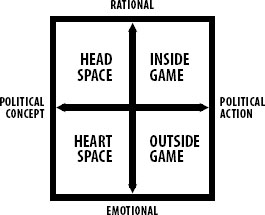

that all four of the quadrants of the grid be activated at different stages.

Sometimes the process moves in the order I have just laid outâfrom sober analysis and facts (Head Space), to resonant narratives that inspire support (Heart Space), to citizen participation (Outside Game), to official debate, deal making, and rule making (Inside Game). Sometimes it starts in the Heart Space with an impassioned call for change, which activists then pick up on a mass scale (Outside Game), which in turn catalyzes scholars and think tanks (Head Space), and ultimately leads to elected officials changing laws (Inside Game). The flow can shift back and forth between quadrants as well.

More important than a particular order or progression is the balance among the grid sectors. The natural tendency is to try to figure out which quadrant is “the” most important of the four. The answer to that question is simple: each and every quadrant is the most important one at different stages in the process of making change.

Each and every quadrant is the most important one at different stages in the process of making change.

If one's cause is driven purely by emotional outrage and presently lacks any workable policy solutions or constructive ties to people in City Hall or on Capitol Hill, then one should prioritize developing capacities in the top-two quadrants. On the other hand, one might

have bookshelves full of smart policy proposals and know every legislator, aide, and intern at the state capitol but still find oneself losing key votes and decisions. In that case, breaking out of the top quadrants and finding allies who can sell the cause emotionally (Heart Space) and build passionate public enthusiasm for it (Outside Game) will be necessary. The key is to achieve a dynamic balanceâstriving for a kind of “full-spectrum dominance” across all four quadrants.

Next, I will use this framework to reexamine and shed new light on the events and phenomena described at length in the previous chapters.

CAMPAIGNING VS. GOVERNING

At the start of the 2008 campaign season, Senator Hillary Clinton was eager to own the top half of the grid. She presented herself as an ultra-competent policy wonk (Head Space) who would be “ready on day one” as a master of Washington politics (Inside Game).

But Obama adroitly positioned himself as the candidate of the bottom half. As easy as it is today to dismiss the hope-and-change phrase as a corny cliché, much of the work in 2007 and 2008 was simply convincing people that change was even feasible. That task required overcoming cynicism, reviving a sense of possibility, and getting people to shake off the funk of the Bush years.

Such work is handled best by someone who knows how to touch hearts and move the masses. That person, in 2008, was Senator Barack Obama.

First of all, Obama personified resonant communication, in every way. In his own understated way, he was as much performance artist as political candidate. He spoke poetically; he owned

the stage and embodied the narrative, transforming his personal biography into a powerful statement about the strength and beauty of America itself. He was and is a beautiful man, inside and out, with a beautiful family. It is true that in the middle of most of his speeches, he would slog through a ton of policy detail. But nobody left telling her or his friends and neighbors about that. Obama would begin and close every speech in a moving and heartfelt way, and that is what people remembered.

Obama did not carry the weight of inspiring the country all by himself, either. His cultural and artistic sensibility touched something in other artists. They jumped into the mix in unprecedented and remarkable ways.

Everyone remembers the famous Will.i.am video, “Yes We Can,” which got millions of views on YouTube. Most people watching the video probably assumed the oratory that Will.i.am sampled came from an Obama victory speech. But it did not. Obama gave the speech in the depths of defeat; after his rival Clinton got misty-eyed in a diner, Obama fell in the polls by more than twenty points in forty-eight hours and lost to her in New Hampshire. By letting herself become vulnerable (Heart Space!), Clinton pulled off one of the great upsets in the history of presidential primary politics. Defeated, Obama walked out and gave the “Yes We Can” addressâas a concession speech. But Will.i.am and other artists were so impressed by Obama's strength and determination that they jumped in, remixed it, added music, and presented Obama to the world as a poised and powerful leader. Everyone just assumed they must have been looking at a winner.

That is the power of the Heart Space. The appeal of music, celebrity, and film can overrun stodgy political realities and transform them. The cold mathematics of politics left Obama a loser,

but the magic of artistic expression stole that moment away from Clinton and helped turn Obama back into a winner.

Other artists played important roles, too:

⢠Comedienne Tina Fey eviscerated GOP vice presidential nominee Sarah Palin week after week on

Saturday Night Live

, essentially making Palin unelectable. Humor is an important tool in expressing and shaping emotions.

⢠The “Obama Girl” video, in which a beautiful songstress declares, “I got a crush on Obama,” introduced the freshman senator to millions of people who were beyond the reach of ordinary politics.

⢠Shepard Fairey's iconic “Hope” posters helped to create the heroic mythos that enveloped the candidate. Thousands adapted the image in creative ways and spread the meme even further.

⢠And of course, there was the Obama “Rising Sun” logoâthe symbol of the campaign. Its power is rarely mentioned in popular campaign histories, which focus mainly on voter turnout strategies and daily campaign tactics. But at the street level and in popular culture, the logo became the Nike swoosh of politics, turning Obama into the ultimate aspirational brand.

After the election, just before the inauguration, the artists came out in force. At the “We Are One” concert, the world's glitterati arrived to celebrate and performâfrom Stevie Wonder, to U2, to Beyoncé. (Unfortunately, that concert was the last time the full glory of the artistic community was marshaled in service to the cause.)

The campaign was extraordinary, not just because it dominated the Heart Space. It also dominatedâand even reinventedâthe Outside Game.

There were big, super rallies where tens of thousands of people would come out, as if going to a big tent revival or a major concert or sporting event. These were emotional events, not intellectual ones. The rallies and mass gatherings helped to fuel and define the campaign itself.

The campaign was designed to capture such enthusiasm, thanks in part to Chris Hughes, who decamped from Facebook to lend his support to Obama for America. He built an interactive campaign platform called

MyBarackObama.com

. Some of the hardened operatives and bean counters who ran the campaign's GOTV logistics thought of the website as a kind of cute and fluffy add-on. In a purely technical sense, perhaps it was.

But as a mechanism for mass-producing goodwill and creating momentum,

MyBarackObama.com

played an invaluable role. Anybody in America could immediately sign up, join a campaign-related group, or create one, and be a part of something historic. Even if the person didn't do anything after she signed up, she still felt like she was a part of something special. The psychological impact on Obama's broad base of supporters was electrifying.

Also, Harvard University lecturer and United Farm Workers veteran Marshall Ganz helped to create a training program for campaign volunteers called Camp Obama. It trained thousands of people in 2007 and then sent them all over the country, with no money, offices, or official titles. On their own, those graduates spread out and built massive networks and campaign organizations,

in a remarkable act of distributed electioneering. Those organizers made it nearly impossible for Clinton to win caucus states.

A deeper look at the grid reveals something important. The upper half of the grid (Head Space + Inside Game) is vital to institutionalizing and formalizing social change. It is about economics and politics, as those are traditionally understood. It is key to getting formal decision makers to codify and implement structural reforms. In the language and context of the Obama 2008 campaign, we could say that the top half of the grid is about “change.”

The lower half of the grid (Heart Space + Outside Game) is vital to freeing the human spirit and unleashing the energy necessary to make any change. It is about the cultural and spiritual dimensions of the movement. It is key to nurturing a sense of greater possibilities and getting millions of inspired people to take action together. In the language and context of the Obama 2008 campaign, the bottom half of the grid is about “hope.”

Both halves of the grid need each other. As a practical matter, elections are the bridge between hope and change, particularly between the Outside Game and Inside Game. The relationship between the two halves can be symbiotic: hope is usually a prerequisite for positive change, and positive change can help sustain hope. The power of the 2008 Obama campaign came from the fact that it touched on all four quadrantsâthe need for economic and political reform (“change”), as well as the belief in a brighter future that included spiritual renewal (“hope”).

Hope is usually a prerequisite for positive change, and positive change can help sustain hope.

Winning the election theoretically put Obama and the movement that elected him into a position to fortify dominance of

the lower half of the grid, while conquering the upper halfâmaintaining hope, while delivering change.

But such was not to be. As Team Obama attempted to master the Inside Game, the color and dynamism of the Outside Game collapsed. As we have discussed earlier, there were no marches or protests in support of the agenda. Even the grassroots seemed more interested in “access” than activism. Mega-rallies that featured inspirational artists or Obama were no more.

And as the administration wrestled with the policy nuance of the Head Space, the passionate fires of the Heart Space were left unattended. President Obama began to sound more and more like a regular politician. Perhaps that was inevitable. As Mario Cuomo, former mayor of New York City, said long ago, “We campaign in poetry. We govern in prose.” Still, one imagines that other artists, celebrities, and spokespersons could have been enlisted to continue some of the cultural and spiritual aspects that made the 2008 campaign so resonant.

Unfortunately, Obama and his supporters decamped for the top half of the grid, abandoning the lower half. That move left the door open for the Tea Party backlashers to sweep into the lower quadrants uncontested in 2009âand take over practically the entire grid in 2010.

As Americans continued to suffer the ongoing consequences of the financial crisis, and as the nurturing aspects of the hope-and-change campaign dissolved, the pain in America's heart intensified. Everyday people needed their sense of loss and fear acknowledged. People needed a story that made sense of the pain.