Real Food (9 page)

Authors: Nina Planck

Milk from cows treated with rBGH contains higher levels of IGF-1, a naturally occurring growth hormone that is identical in

cows and humans. When you drink a glass of milk from a cow treated with rBGH, you get a dose of IGF-1, one of the most powerful

of many insulinlike hormones that prompt cells to grow and proliferate. IGF-1 is linked to cancers of the reproductive system,

including breast cancer. Because the FDA regards rBGH as safe for human consumption, it does not permit dairy farmers to print

"hormone-free" on milk labels, but most dairy farmers who

don't

use hormones find a way to say so. If the label is silent, it's a safe bet the cows were treated with rBGH.

What kind of milk should you buy? Traditional milk is ideal and organic milk second-best. Both are better than industrial

milk. Unfortunately, most commercial organic milk comes from cows fed grain, not fresh grass. (All cows must eat some hay

for roughage.) Organic cows must have "access" to pasture, but on many large organic dairies, cows spend very little time

outside. Grass-fed milk is best, even if it's not organic. Most grass farmers feed cows on grass and hay with a small grain

supplement at milking, as I fed Mabel. That's acceptable, because even an ancient wild cow would have eaten some grain from

seed heads.

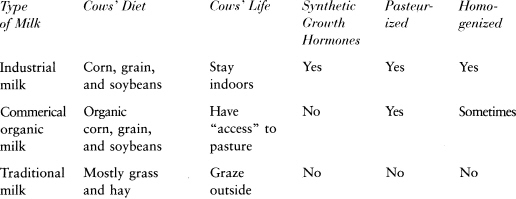

INDUSTRIAL, COMMERCIAL ORGANIC, AND TRADITIONAL MILK

The best choice is traditional milk, but it's not easy to find. Farmers who supply two organic brands, Organic Valley and

Natural by Nature, raise cows on pasture. By law, no milk includes antibiotics. If a cow needs antibiotics, her milk is discarded

until the drugs have cleared her system.

Perhaps the greatest difference between traditional and modern milk is pasteurization, routine since the middle of the twentieth

century. The French chemist Louis Pasteur invented pasteurization, a form of heat sterilization, in the 1860s to improve the

keeping qualities of wine and beer. Gentle pasteurization heats the milk to 145 degrees Fahrenheit for thirty minutes, and

standard pasteurization heats it to 161 degrees for fifteen seconds. Ultrapasteurized milk is held under pressure at 280 degrees

for two seconds. Milk labeled UHT— ultra high temperature— is ultrapasteurized and then packaged in aseptic boxes sterilized

with hydrogen peroxide.

Pasteurization is generally regarded as a sign of progress, a boon for public health— and there is much truth in that. Pasteurization

does destroy certain pathogens, including salmonella,

E. coli,

and campylobacter. However, pasteurization also destroys vitamins, useful enzymes, beneficial bacteria, texture, and flavor.

The push for pasteurization in the United States began in the late 1800s and the early 1900s. It was a response to an acute

and growing public health crisis, in which infectious diseases like tuberculosis were spread by poor-quality milk. Previously,

milk came to the kitchen in buckets from the family cow or in glass jars from a local dairy, but soon, urban dairies sprang

up to supply the growing populations in or near cities such as New York, Philadelphia, and Cincinnati.

Owners put the dairies next to whiskey distilleries to feed the confined cows a cheap diet of spent mash called distillery

slop. For distribution, the whiskey dairies were efficient: in 1852, three quarters of the milk drunk by the seven hundred

thousand residents of New York City came from distillery dairies. The last one in New York City (in Brooklyn) closed in 1930.

The quality of "slop milk," as it was known, was so poor it could not even be made into butter or cheese. Some unscrupulous

distillery dairy owners added burned sugar, molasses, chalk, starch, or flour to give body to the thin milk, while others

diluted it with water to make more money. Slop milk was inferior because animal nutrition was poor; cows need grass and hay,

not warm whiskey mash, which is too acidic for the ruminant belly. Recall from Blossom that cows on fresh grass produce more

cream, a measure of milk quality.

Conditions were unhygienic, too. In one contemporary account cited in

The Complete Dairy Foods Cookbook,

distillery cows "soon become diseased; their gums ulcerate, their teeth drop out, and their breath becomes fetid." Cartoons

of distillery dairies show morose cows with open sores on their flanks standing or lying in muck in cramped stables. Bovine

tuberculosis and brucellosis were common, and cow mortality was high. The people milking the cows were often unsanitary and

unhealthy, too. Dairy workers could taint milk with human tuberculosis and other diseases.

A public health crisis was brewing. As distillery dairies became common around 1815, contaminated milk caused fatal outbreaks

of diseases including infant diarrhea, scarlet fever, typhoid, tuberculosis, and undulant fever (the human version of brucellosis).

Infant mortality, often due to diarrhea and tuberculosis, rose sharply, accounting for nearly half of all deaths in New York

City in 1839. Reformers blamed the outbreaks of disease on slop milk. The distillery dairies were like the sausage factories

later exposed as dirty and unsafe by Upton Sinclair in his 1906 novel

The Jungle.

Regulation was desperately needed.

Reformers suggested pasteurization to kill pathogens carried in milk. At first, no one suggested that raw milk itself was

unsafe, according to Ron Schmid in

The Untold Story of

Milk

— merely that milk should be clean. "Demands for pasteurization allowed for the continued production and sale of clean raw

milk," writes Schmid, a naturopathic physician. "No one was claiming that all milk should be pasteurized, as even the most

zealous proponents of pasteurization recognized that carefully produced raw milk from healthy animals was safe."

This view prevailed, briefly. When a raw milk ban was proposed in New York City in 1907, a coalition of doctors, social workers,

and milk distributors defeated it, arguing that safe milk should be guaranteed by inspections, not pasteurization. In 1908,

however, a panel of experts appointed by President Theodore Roosevelt concluded that raw milk itself was to blame for food-borne

illness. That was the final blow. In 1914, New York required pasteurization of milk for sale in shops. Other states followed

suit, and by 1949, pasteurization was the law in most places.

The moral of the tale is clear: the trouble starts when you take a cow away from her natural habitat and healthy diet and

force her to become a mere milk machine. By abusing the hapless cow, the distillery dairy owners put human health at risk.

Slop milk

was

responsible for thousands of cases of illness and death— most of them preventable by improving cow health and dairy hygiene.

But mandatory inspections were not the expedient solution to the crisis; pasteurization was.

Today, thanks to better animal nutrition, hygiene, and widespread testing, the tuberculosis and brucellosis that ravaged nineteenth-century

populations (bovine and human) are rare. Yet even now, when slop milk is long gone, pasteurization plays a vital role in the

commercial dairy industry. FDA rules say that "raw dairy products shall not be shipped across state lines for direct human

consumption." Every day, tankers of raw milk rumble down American highways, but the milk is pasteurized before it's sold to

you or me. "For the purpose of current commercial distribution of milk, pasteurization is an undoubted necessity," writes

Grohman, a lively advocate for raw milk, in

Keeping a Family Cow.

Why?

The typical dairy farmer pours warm milk into a refrigerated tank after milking. Every few days, a truck goes from dairy to

dairy collecting raw milk. Thus the milk of thousands of cows is blended before being shipped to the bottling plant or cheese

factory. Pasteurization after collection can prevent contaminated milk from one sick cow, unhygienic dairy worker, or dirty

nozzle from tainting the clean milk of dozens of other dairies.

Pasteurization also has practical benefits for the dairy industry: it permits more handling, long-distance shipping, and longer

storage. Fresh milk doesn't travel well. Jostling damages its delicate fats and sugars and causes milk to sour. Raw milk lasts

about a week, but standard pasteurization extends the shelf life of milk to two or three weeks. Ultrapasteurized milk keeps

for eight weeks, and aseptic UHT milk can last ten months without refrigeration.

In practice, pasteurization can have an unsavory effect on hygiene in the dairy. It allows less scrupulous dairy farmers to

be lax with cow health and milk handling because they count on pasteurization to destroy pathogens— at least the heat-sensitive

ones— that may taint milk. Many dairy insiders believe that dairy inspections, despite the lessons of slop milk, are still

inadequate. I've seen some not very clean dairies myself.

Nor does pasteurization guarantee protection against food poisoning. Pathogens such as

Listeria

can survive gentle pasteurization.

22

According to the Ohio State University Extension Service,

Listeria

is slightly more heat-resistant than many other bacteria such as salmonella and

E. coli,

and will grow at temperatures as high as 140 to 150 degrees Fahrenheit. (Recall that gentle pasteurization heats milk to 145

degrees.)

Finally, like any food, both raw and pasteurized milk can carry pathogens. Milk may be contaminated at any point

after

pasteurization— in handling, transportation, storage, or cheese making— just as easily as before. Indeed, the majority of

dairy-related food-poisoning cases are traced to pasteurized milk and cheese.

WHY IS FOOD POISONING ON THE MARCH?

Outbreaks of food-borne illness caused by salmonella and other pathogens have risen steadily since pasteurization became standard.

The reasons aren't well understood, but salmonella and

E. coli

thrive under the conditions typical in factory farms, including grain feeding, overcrowding, and rapid, mechanized slaughter.

Overuse of antibiotics on factory farms has also led to resistance to common antibiotics in strains of salmonella, campylobacter,

and

E. coli.

Whatever the cause, the recent advances of these pathogens cannot be blamed on raw milk. When raw milk was the norm, these

threats were less common. (For more on a dangerous form of

E. coli

that thrives in grain-fed beef cattle.)

Traditional milk differs from industrial milk in one other important way: it is not homogenized. If unhomogenized milk is

left to stand overnight, the cream, which is lighter, rises to the top. This is good, because the amount and color of the

cream (the yellower, the better) have always been the measure of milk quality, and even today farmers are paid more for more

butterfat.

Homogenization forcefully blends the milk and cream, so they never separate. Devised in France around 1900 to emulsify margarine,

homogenization pumps milk at high pressure through a fine mesh, reducing its fats to tiny particles. Industrial milk (and

even cream) are homogenized during or after pasteurization.

In the United States, homogenization became common soon after pasteurization, largely because it solved two practical problems

for the dairy industry. The first was the inconvenient separation of the milk and cream. With pasteurization it was possible

to ship milk long distances, but the cream rose in transit, which meant the most valuable part of the milk— the fat— was unevenly

distributed from one customer to another. Homogenization spreads the cream throughout the milk, so everyone gets a share.

The second problem was cosmetic. After pasteurization, dead white blood cells and bacteria form a sludge that sinks to the

bottom of the milk. Homogenization spreads this unsightly mass throughout the milk and makes it disappear.

For many years after its introduction, many Americans declined to buy homogenized milk. "Skeptical consumers were disturbed

both by the change in flavor and the absence of the cream line at the top of the bottle," writes Schmid in his milk history.

But dairy companies persisted with a campaign to win the public over, and by the 1950s, most milk was homogenized.

Homogenization is entirely unnecessary. It's also ruinous for flavor and texture. It breaks up the delicate fats, producing

rancid flavors and causing milk to sour more quickly. According to McGee, it takes twice as long to whip homogenized cream,

because the fat particles are smaller and more thickly coated with milk protein. I would only add that unhomogenized whipped

cream is noticeably more delicious. The best cheeses, too, are made with unhomogenized milk. Happily, unhomogenized milk is

perfectly legal, and a few smaller dairies still sell it, sometimes labeled "cream top" or "cream line." If you find that

whole milk with cream on top is too rich to drink straight, just pour off the cream and put it on apple pie.

I Describe the Virtues of Raw Milk

BERNARR MACFADDEN WAS A body builder of the rippling-chest variety you see in old comics. Born in 1868, he was a sickly child

but overcame his weak start to become a champion of outdoor activity and fitness. Like many reinvented Americans, he changed

his name (choosing a funny spelling) and transformed his body by lifting weights. Macfadden kept fit by walking the twenty-five

miles from his house in Nyack to New York City— barefoot. In a long, flamboyant career, he became rich and famous selling

exercise equipment and publishing fitness manuals, often using his own splendid physique to illustrate poses akin to Greek

statuary. At the age of sixty-five— if pictures don't lie— Macfadden had the sort of body readers of

Men's Health

dream of: a hulking, inverted-pyramid torso atop narrow hips and bulging thighs. Macfadden attributed his fine form to raw

milk.