Rampage (33 page)

Authors: Lee Mellor

On the evening of Friday, August 9, 1991, Nina arrived at Burlington’s Cedar Springs Racquet Club only to discover that she had mistaken the starting time of her round-robin tournament and missed it. Brimming with energy, and with a half hour to kill before her father arrived, Nina decided to burn off her frustrations by jogging along a nearby service road. Dusk was settling on the city of Burlington, and she could hear the chirping of crickets from the nearby grass. In this safe upper-middle-class area, it was not unusual for club members to take a quick run around the block. To disappear suddenly into the warm summer night, however, was something nobody was prepared for. Half an hour later, Rocco de Villiers finished his racquetball game and settled down to wait for Nina at the club coffee shop. When she failed to arrive, he spoke with the attendant at the front desk and learned that she had left her car keys in their care. This troubled him — Nina was never one to stand somebody up. Concerned, Rocco nevertheless acknowledged that his daughter was a full-grown adult, and returned home to await news from her. It never came.

By dawn, friends, family members, and staff began to search the area around the club. At 9:00 a.m. a fitness instructor found Nina’s rainbow headband in the shade of a nearby willow tree. Now the authorities were willing to take the missing person case seriously. When Sheila Yeo learned the news that Nina’s disappearance coincided with her husband’s, she telephoned the Niagara police immediately and informed them of Jonathan’s past.

Three days later, in Petitcodiac, New Brunswick, twenty-eight-year-old Karen Marquis finished work at the Moncton rail yards and chatted briefly with her husband, Neil, who was just beginning his afternoon shift, before heading home to watch some videos. Just after midnight, Neil pulled into the couple’s driveway to find Karen’s car parked in his spot. Upon entering the house he noticed that coffee had been spilled on the kitchen floor, and he called for his wife. No response. Neil headed downstairs, where he expected to find Karen curled up with her movies. Both the VCR and television were turned on, but there were no signs of her. It wasn’t until he searched the rest of the house and stumbled over something in the upstairs hallway that he discovered the shocking truth. Concealed beneath a pile of blankets lay the body of Karen Marquis — shot at close range through the head.

It didn’t take long for police to find the killer’s mode of entry — a broken downstairs window bearing two clear fingerprints. Within two hours they were matched to Jonathan Yeo, and a warrant for his arrest was issued across Canada. A forensic swabbing of Karen’s body revealed traces of semen in her vagina and rectum. Among the items missing from the house were the two romantic comedy movies that Karen had rented, her wallet and keys, and

Playboy

magazines from an upstairs cupboard.

On August 13, Jonathan was sighted a number of times 130 kilometres west of Hamilton in London, Ontario. That afternoon he had unsuccessfully attempted to cash a cheque for $50 at a local bank. Later, he was seen at a bowling alley talking to the machines in the adjoining arcade before leaving at around 10:00 p.m. Sometime after, a twenty-five-year-old woman escaped his clutches and identified him as her would-be abductor. With Jonathan’s return to the area confirmed, Hamilton-Wentworth police contacted Alison Prescott, advising her to stay clear of her apartment.

The next afternoon, Jonathan’s brown Toyota was spotted driving on Hamilton Mountain. With two cruisers on his tail, the police dragnet began to close. Realizing that, if caught, he would be spending the rest of his life in prison, Jonathan decided enough was enough. Struggling to steer as he placed the barrel of the rifle into his mouth, he took one last breath and pulled the trigger. Eight hours later, he was pronounced dead.

Two days after Jonathan’s suicide, the naked, decomposed body of Nina de Villiers was found floating in a creek between Napanee and Kingston, Ontario. She had suffered a gunshot wound to the back of the head. Despite the nude state of the body, the coroner found no evidence of sexual assault. Back in Burlington, investigators had located spots of blood under a willow tree near the racquet club, and surmised that Nina had been shot there execution-style. Judging by the dearth of blood and injuries to the back of the skull and spine, her death had probably been instantaneous. If the killer had not raped or robbed his victim, then the motivation for the attack was presumably anger. Bloodstains located by forensics investigators on the back seat of his car indicated where Jonathan had stowed Nina’s corpse after the shooting. An eyewitness claimed to have seen the crazed Dofasco worker pulling out of the racquet club between 9:30 and 10:00 p.m., giving him a chilling stare as he passed. The dumpsite, exiting Highway 401 onto Highway 133, was 286 kilometres east of where Nina had been murdered. Likely Jonathan had spotted the secluded bridge from the highway and pulled off to secret Nina’s body underneath it.

Caveat

Following an inquest into the Jonathan Yeo murders, Nina’s mother, Priscilla de Villiers, drafted a petition to the federal government demanding that violent crimes be taken more seriously, and that laws regarding bail and parole be changed in accordance. No longer should justices of the peace be allowed to conduct bail hearings; instead, the hearings should be subject to the consideration of a judge. Furthermore, the rights of violent offenders should not take precedence over the safety of society at large. Priscilla spoke out in favour of the petition at church organizations, service clubs, and women’s groups. Everywhere she went, she found her fellow Canadians in staunch agreement with her proposals. Among them was Karen Marquis’s mother-in-law, Jean, who travelled by train from city to city collecting signatures. The end result was not only a petition containing hundreds of thousands of names, but the forming of

CAVEAT

(Canadians Against Violence Everywhere Advocating for its Termination), a non-profit corporation dedicated to constructive justice system reform. For more information, see

www.caveat.org.

*

A pseudonym.

Part D

MASS MURDERERS

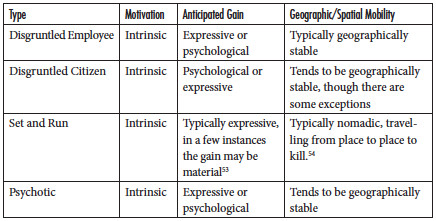

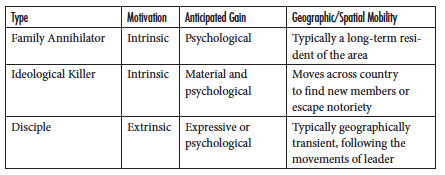

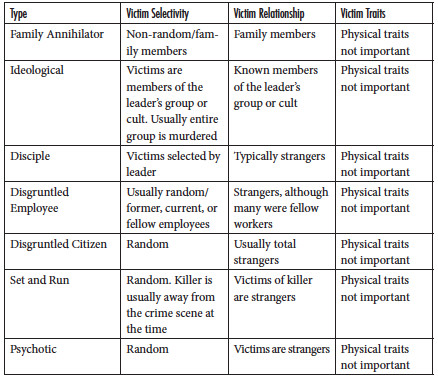

Table 8: Holmes and Holmes’s Typology of Mass Murderers

*

*

This table is an amalgamation of traits and characteristics outlined for the various mass murder categories found in Holmes and Holmes’s Mass Murder in the United States.

Chapter 8

The Family Annihilator

Statistically, the majority of homicides in Canada occur between acquaintances (approximately 0.5 per 100,000 people) or family members (approximately 0.4 per 100,000 people).

[55]

Simply put, despite the sensationalism surrounding serial murderers, you are more likely to die at the hands of somebody you know than any sex maniac or unscrupulous gangster. The first category of mass murderer we examine reflects this unsettling trend. As we have seen in the

Cook

,

Swift Runner

,

Easby

, and

Sovereign

slayings, the Family Annihilator is by far the most common mass killer, though their motivations vary from profit (Cook) to psychosis (Swift Runner) to anger (Sovereign). Whereas in other chapters I have been forced to rely on American or British cases to provide brief preliminary examples of types of rampage murderers, there is such a grim legacy of domestic mass murders in Canada that in this instance, we need not look outside our own borders.

In the mid-nineteenth century, Quebec resident Mathilde Laventure succumbed to madness and murdered her seven children, who ranged in age from thirteen years down to four months. The thirty-three-year-old mother then committed suicide and, atypically for a Catholic, was buried on consecrated ground, having been deemed insane.

Alberta politician John Etter Clark went similarly nuts in the summer of 1956, borrowing a .22 -calibre rifle from his uncle. He then fatally shot his wife, Margaret; four children; a farm hand; and a visitor. After fleeing 550 metres from the crime scene, Clark put a bullet through his own skull, bringing the final death toll to eight.

Swearing vengeance against the wife, who had divorced him, on April 6, 1996, Mark Vijay Chahal entered her family’s home in Kamloops during preparations for her sister’s wedding. Wielding dual pistols, he massacred nine members of the family, including his estranged wife, before committing suicide in a hotel room.

Vancouver policeman

Leonard Hogue

’s motives are particularly fascinating: slaughtering his entire family seemingly in order to spare them the details of his crimes.

Other Family Annihilator mass murderers in this book:

Thomas Easby, Henry Sovereign, Robert Raymond Cook

Kay Feely

Leonard Hogue

Victims:

7 killed/committed suicide

Duration of rampage:

April 19 or 20, 1965 (mass murder)

Location:

Coquitlam, British Columbia

Weapon:

.357 Magnum revolver

Money for Nothing

On August 8, 1963, a team of armed robbers stopped a Royal Mail train near Bridego bridge in Ledburn, England. Contained within its steel walls was a cache of used banknotes scheduled for destruction. In the space of fifteen minutes, the hijackers boarded the train and made off with 2.6 million pounds. Amazingly, during the robbery, most of the employees remained blissfully unaware that anything unusual was happening. Though twelve of the fifteen gang members were eventually convicted, the heist would go down as one of the most brilliant and brazen in British history.

We may never know if Constable Leonard Hogue and his accomplices were inspired by the Great Train Robbery of ’63, but it is hard to imagine they were unaware of it. On Thursday, February 11, 1965, three men walked up to the Canadian Pacific Railway Warehouse at 44 Pender Street in Vancouver. Noting that one of the strangers was dressed in a CPR policeman’s uniform, the attendant allowed them to enter. Once inside, they pulled a gun on a clerk and demanded access to boxes of used banknotes scheduled for incineration at Ottawa’s Royal Mint. Encountering no resistance, the trio managed to haul three three-hundred-pound fibreglass boxes to their getaway vehicle — a station wagon — before speeding away. Their plan had seemingly come off without a hitch. Unfortunately, they had no idea that the currency had been mutilated specifically to prevent such abuse, and was completely worthless. One thing seems reasonably certain, though: when Leonard Hogue first laid his eyes on the bills, each one punctured with three half-inch holes, he would have been devastated. Not only had the thirty-four-year-old constable put his reputation and freedom at stake, he had done so for nought.