Ragnarok 03 - Resonance (25 page)

Read Ragnarok 03 - Resonance Online

Authors: John Meaney

Descent was straightforward; only upward movement required authorisation.

Fifteen more descents, and they were in a region of raw tunnels lit â and given habitable atmosphere â by ceiling fluorofungus, where dwelling-tunnels featured rows of hollowed-out al-coves that served as homes, and dumb-fabric hangings served

as doors and interior walls, and the people were on the whole kind to each other, because this was a community strong in the face of poverty, where working together meant survival.

It was a good place to find a hospice, run by older folk with steady eyes and plain speech, who would not turn away the young girl-woman left at their door by a silent, hooded figure â her clothes far too rich for this stratum â who slipped away without greeting anyone. They helped Mandia inside with kindness.

Kenna moved on.

Other people were beginning to follow her, made suspicious by her clothing and lack of speech, so when the tunnel curved and her pursuers were out of sight, she broke into a run, moving fast and easily now, until she came to a high chamber formed of natural, raw rock in which a lava pool glowed and bubbled.

Dead end.

I will not fight them.

Let them wonder at her disappearance. She stared at the lava pool.

This will be fine.

With a neat motion, she dived into the molten lava and swam downwards through the hot, viscous liquid rock, not caring as her garments burnt away and the heat grew stronger, because this was freedom and wonderful. Something brushed against her â she felt angular flukes â and knew it for the one of the little studied native forms that lived inside the magma, and drew inspiration from the ease with which it moved here.

This world will be good enough.

Give it a millennium or two, she thought as she swam, and then she would move on. There was no hurry.

It would take time to become the person she needed to be.

EARTH, 1972 AD

Alone in her flat, Gavriela lay one slightly arthritic hand upon a project notebook and said to no one at all: âI always thought it would be the death of me.' But here she was, sixty-four years old and mostly healthy, mostly retired, mostly enjoying life. A label on the notebook's front cover explained the project's name:

High

Energy

Interstellar

Meson

Detection,

Amplification &

Lensing

Lattice

It rarely spooked her these days, the thought that she had written out an identical description during wartime Oxford, scribbling in her personal notebook

while asleep

, something she had never done before or since. When Charles, her department head at Imperial, had first suggested she take over the meson research team and showed her the name of a project that Lucas Krause had proposed, he had actually been concerned for her health because of the blood draining from her face. But she had recovered and accepted the job, and nothing had come of it save for a wealth of readings concerning the behaviour of mesons from cosmic rays.

Their decay-time was affected by relativistic distortion, because their velocities were so high, providing one more validation of Einstein's work: her hero, who had once played her

nine discordant notes upon his violin, as an indication that they had more in common than a love of physics.

And Lucas Krause, whose team she had taken over when he left, was the same Lucas she had known as a student at the Erdgenössische Technische Hochschule, where Einstein had previously studied and even taught a little. There had been a brief period when she had taken to spending the occasional night at Lucas's house â romance and physical love were never frequent features in her life â but he had finally returned to his estranged wife in Nebraska, on hearing that she was diagnosed with cancer.

That was five years ago, and Mary Krause was still alive and doing well, which Gavriela was glad of.

Inside the notebook was tucked a typewritten note from one of her Caltech acquaintances, someone she had met at several conferences and was a good contact, because he worked with Gell-Mann frequently. He said that a few people were talking about renaming the meson family members â K mesons, µ mesons and Ï mesons would now be known as kaons, muons and pions respectively â and asking what Gavriela thought of the notion.

She had not yet replied, uncertain whether her natural response would be perceived as European snobbery: that people should use Greek letters, along with Latin terms, as much as possible, and that furthermore there was no excuse for any physicist not to read the Cyrillic alphabet, and realise just how much Russian was comprehensible, especially since modern vocabulary so often resembled French or German.

Then she smiled, remembering Gell-Mann's reputation as a polymath and polyglot who insisted on correct pronunciation of all foreign terms, and decided that she would write her reply exactly as it came to mind.

Earlier today, at half past eight, she had written a one sentence entry in her diary, after receiving an important phone call â fulfilling the reason she had got the Post Office to install

a home telephone in the first place, as soon as she had heard that Carl was an expectant father.

Today I became a grandmother.

It was an echo of the day Carl was born, and more comforting than she had expected, the thought of continuity despite personal mortality.

(She had asked the engineer, when he was installing the phone, whether he had heard of a gentleman called Tommy Flowers. He had said no, then winked, causing Gavriela to smile. Within the next few years, thanks to the thirty-year rule regarding secrecy, the British public would begin to learn how her friend Alan had invented computers and how Tommy built the first, and incidentally shortened the war by two years at least, and perhaps made the difference between victory and defeat.)

The phone rang, one-two, one-two, left-right, left-right as she hurried to the hallway and picked up the receiver.

âIs everything all right?' she said, expecting Carl.

âMost assuredly, old thing,' came a familiar patrician drawl. âWhy ever would it not be?'

âRupert.' She closed her eyes. âI thought Carl might be calling from St Mary's.'

âHe's in church praying for a miracle?'

âI mean the hospital. Alexander Fleming, penicillin, and now my first grandson,' she said.

There was a short silence.

âThat's really most excellent news, dear Gabby.' He would not use her real name on a phone line. âMost excellent.'

âYes, it is,' she said. âAnd an indication that I'm far too old to work for you, dear Rupert. Assuming you've a little job you wanted me to carry out.'

Another silence.

âI do that, don't I?' said Rupert. âIgnore you unless I want something.'

That was disconcerting.

âAre you all right?'

âYes . . . I was hoping we could meet up, not for work, and have aâ'

âSpot of tea,' she said. âYou do that as well. And I'd love to.'

âYou would?' He sounded more cheery. âFancy a stroll around the British Museum?'

âSo one old mummy can cast an eye over the others? I'd be delighted, dear Rupert.'

They agreed to meet in an hour, and then she hung up.

From the outside, the British Museum, like all the other major buildings in London, was a single massive block of soot, black and off putting. Inside it was airy, calming Gavriela down as she passed the Elgin Marbles â relics of one dead empire stolen by another, whose patrician classes were finally realising they had been trained to rule a quarter of the globe that was no longer theirs â and then stood in front of the dark stone Book of Gilgamesh, realising she was in the presence of the world's first written story, not quite able to process the thought.

Rupert, when he appeared, was wearing a bow tie of lapis-lazuli blue, a touch of startling colour; but his pinstripe suit was as conservative as ever: narrow lapels unlike the modern look, and not a hint of flare to the trousers. His oiled hair was iron grey, combed from a parting that was geometrically exact.

They strolled around saying little, finally stopping in the Viking room upstairs, where a wide metal bowl hung on chains from the ceiling.

âCooking-pot,' said Gavriela.

âThe inscription saysâ'

âIt's wrong.'

He raised an eyebrow, as if to ask when she had become an archaeologist, but said nothing. Gavriela had been expecting pointed irony.

âHow's Brian?' she asked, wondering if that was where the problem lay.

âShacked up with a dance choreographer in Soho.'

That stopped her. âOh, Rupert.'

âThe fellow's fifteen years younger than I am.' This was bitterness such as Gavriela had never heard, not from Rupert. âAnd here I am among the antiquities. No jokes about old queens, please.'

She slipped her arm inside his. âI was going to suggest that pot of tea,' she said. âAnd perhaps a nice chocolate biccie to dunk in it.'

They sat in a noisy corner of the tea-room, which was better than silence for private conversation. Gavriela was finishing her tea when Rupert said, âI've other news.'

âWhat is it?'

âSomething best learnt when one has placed the cup back on the saucer, dear Gavi.'

She put it down carefully.

âAt least I'm already sitting,' she said. âI take it you have smelling salts in case I decide to faint.'

âNot an eventuality I thought of, quite frankly. It's just that in addition to becoming a grandmother . . . Congratulations, by the way. I mean it.'

She patted his hand.

âYes, I know you do. And I'm getting nervous. Whatâ?'

âYou're also due to become a great aunt,' he told her. âIn three months' time, give or take.'

Several blinks accompanied her search for meaning in his words.

âI don't . . . Oh.' It was obvious. âYou mean Ursula.'

Her niece. Step-daughter to Dmitri Shtemenko, defector, for whatever that was worth â the debriefers in the old Wiltshire mansion would have got everything they could from her, but no professional intelligence officer would shared classified material with their family â and living somewhere in Britain, as far as Gavriela knew, for these past, what, sixteen years? That would make her thirty-two or thirty-three, depending on when her birthday fell.

My only niece and I don't know even that.

Or the name that people called her these days. It surely would not be Ursula Shtemenko, or even Ursula Wolf.

âWhen did she marry?' she asked Rupert.

His answer was a short silence, then: âA couple of my schoolfriends were bastards, literally speaking. They had a hard time of it, I grant you, bullied every day for years. But they got through it.'

That was not comforting. She wondered if Rupert were annoyed with Ursula out of principle or because â a better thought â he would have preferred to relay a happier version of events to her, Gavriela.

âCarl wasn't exactly born in wedlock either,' she said.

âHe was, in the only way that matters.' Rupert meant the legal documentation, forged by his department, that had showed Gavriela, or rather Gabrielle Woods, to be a war widow. âSodding Brian, I don't know how you could ever forgive him or me. Especially me.'

She squeezed his pale hand.

âWe did what we had to, all of us, dear Rupert. And as for them . . .' She gestured to a group of young people dressed androgynously, males and females wearing identically flared pastel jeans, their hair equally shoulder length but without the braids a warrior needed to keep the hair out of his eyes â where had that thought come from? â and ridiculous shoes unsuitable for running or agile footwork. âThey'll never know what we went through, but it doesn't matter.'

Give the young folk their due â they did not look like the kind of people who would care about illegitimacy one way or the other. Perhaps her great-niece or great-nephew would not face the same kind of harshness that others used to.

Or her grandson.

âAnna's not married to Carl either.' She had not meant to tell Rupert. âI know I call her his wife, but they haven't ever tied the knot, not legally. She's still Anna Gould.'

Rupert sighed. âYou and I . . . The people in our lives don't have an easy time of it, do they?'

âCursed by gypsies, is that what you mean?'

He finally smiled, his face lean, porcelain skin showing lines. âOn the rare times a game gets out of control,' he said, âI prefer castling as a manoeuvre. A defensive huddle staving off defeat, while I find a way to survive.'

She had always thought of him as playing the chess game of life, and him a grandmaster, but she had never heard him use the metaphor so precisely.

Then he added, âWhy don't you come round for supper?'

âUm . . . You mean to your house?'

âThat's what I was thinking of.'

She had never been there.

âAnd when were you thinking of?'

âTonight. If you're visiting Anna and the baby in hospital, then a late supper, perhaps.'

Was this what he had meant by castling? Old friends spending time in each other's company as a defence against loneliness?

âI'd love to, dear Rupert.'

âWell, good.'

Over the next few weeks, she became a regular visitor to Rupert's Chelsea home, where listening to Brahms or Bach in his drawing-room (not a term she had ever used outside ironic conversation) became a pleasant habit. At Oxford he had read Greats, which the rest of the world called Classics, and his collection of sketches and old books was fascinating.

But there was another postscript to their meeting in the British Museum that she did not share with him at first, because he did not need the worry. He had officially retired from the Service, and his intention was to write monographs on ancient Troy and the relationship between the early Roman Empire and Greece â echoes of Macmillan's speech in '56 regarding Britain and the States â with the benefit of insight gained from a career spent among the secret strategists and covert machinations of international politics.

In her overcoat pocket, when she had recovered it from the museum cloakroom, there had been a photograph, the second time such a message had been left for her. The other time, the picture had shown Ilse and Dmitri, with the girl who turned out to be Ursula; it suggested that this second photo came from Dmitri also, but the darkness did not leave traces in handled material, so there was no way to be sure.

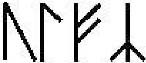

It was consistent with the location, a photograph of a withered, blackened iron blade that might have come from the museum's Roman room, except that Gavriela could read the pattern that surely no one else could see among the creases and folds.