Quirkology (21 page)

Authors: Richard Wiseman

Pellegrini’s work, although insightful, failed to ask about one important trait: honesty. Had he done so, his conclusions about beards may not have been so positive. Recent surveys show that more than 50 percent of the Western public believe clean-shaven men to be more honest than those with facial hair. Apparently, beards conjure up images of diabolical intent, concealment, and poor hygiene. Although there is no relationship between honesty and facial hair, the stereotype is powerful enough to affect the world—perhaps explaining why everyone on the Forbes 100 list of the world’s richest men is clean-shaven, and why no successful candidate for the American presidency has sported a beard or a moustache since 1910.

The beard studies are just one tiny aspect of a large amount of research conducted by psychologists into the effects of facial appearance on perceived personality and abilities. According to research recently published by Alexander Todorov and his colleagues at Princeton University, facial appearance is vitally important in politics.

40

Todorov presented students with pairs of black-and-white photographs containing head shots of the winners and runners-up for the U.S. Senate in 2000, 2002, and 2004. For each pair of photographs, Todorov asked the students to choose which of the pair looked more competent. Even though the students saw the pairs of photographs for just one second, choosing which of the two looked more competent predicted the election results about 70 percent of the time. Not only that, but the degree of disagreement among the students also predicted the margin of victory. When the students all agreed on which of the two candidates appeared the most competent, that candidate emerged the clear winner at the polls. When there was less agreement among the students, the election results were not so clear-cut.

40

Todorov presented students with pairs of black-and-white photographs containing head shots of the winners and runners-up for the U.S. Senate in 2000, 2002, and 2004. For each pair of photographs, Todorov asked the students to choose which of the pair looked more competent. Even though the students saw the pairs of photographs for just one second, choosing which of the two looked more competent predicted the election results about 70 percent of the time. Not only that, but the degree of disagreement among the students also predicted the margin of victory. When the students all agreed on which of the two candidates appeared the most competent, that candidate emerged the clear winner at the polls. When there was less agreement among the students, the election results were not so clear-cut.

Todorov’s work suggests that when it comes to winning seats in the Senate, it is important to have a face that fits. But does a person’s facial features also influence the most important political process of them all—the race for the White House? To find out, I recently teamed up with an expert in facial perception—Rob Jenkins, a psychologist from the University of Glasgow—and carried out an unusual experiment involving twelve of the most powerful men in history.

Most people are quick to associate certain personality traits with certain types of faces. They see a baby-faced individual with large eyes and a round head and instantly assume that the person is honest and kind. Or they meet someone with close-set eyes and a crooked nose and suddenly question whether that person is to be trusted. Like it or not, such stereotypes influence many aspects of our everyday lives, and so it wouldn’t be especially surprising if presidents tend to have the types of faces that are perceived as especially trustworthy and competent.

However, Rob and I were curious about whether facial appearance affects voters in a far more subtle and interesting way. Not surprisingly, research suggests that Democrats and Republicans value different personality traits in their leaders, Democrats being attracted to those who are more liberally oriented and Republicans going for more authoritarian types. Assuming that people unconsciously associate such traits with different facial features, are Democrats and Republicans drawn to very different-looking leaders? Such an effect might influence the way in which party members choose candidates to run for the presidency, or how voters decide which one to put into the White House. Either way, if there is something to the idea, then Democratic and Republican presidents should have very different facial features because different selection pressures are in operation. Rob and I set out to discover whether this was the case.

The work involved a sophisticated computer program that accurately blends several different faces into a single average, or “composite,” image. The principle behind the technique is simple. Imagine having photographic portraits of two people. Both have bushy eyebrows and deep-set eyes, but one has a small nose and the other a much larger nose. To create a composite of their two faces, researchers first scan both photographs into the computer, control for differences in lighting, and then manipulate the images to ensure that key facial attributes—such as the corners of the mouth and eyes—are in roughly the same position. Next, one image is laid on top of the other, and an average of the two faces calculated. If both faces have bushy eyebrows and deep-set eyes, the resulting composite would also have these features. If one face has a small nose and the other a large one, the final image would have a medium-sized nose. The process is totally automated and can be used to merge any number of faces.

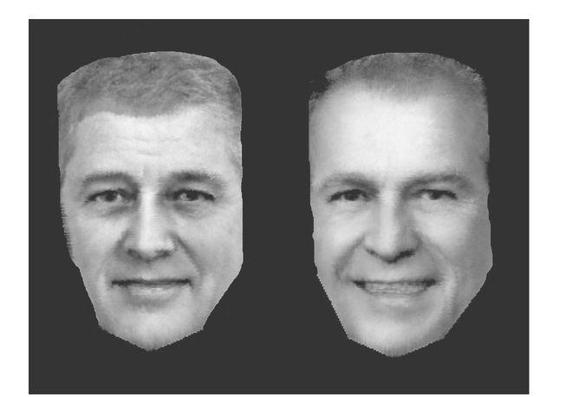

Rob tracked down photographic portraits of the last six Democratic (Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy, Johnson, Carter, and Clinton) and Republican (Eisenhower, Nixon, Ford, Reagan, Bush Sr., and Bush Jr.) U.S. presidents, ensuring that the portraits in each group showed the presidents with the same facial expression and looking in the same direction. He then digitally removed Harry Truman’s glasses, fed all the images into a computer, and created a composite for each group of presidents. The results were astonishing. As predicted, the blend of the six Democratic presidents looked very different from the six Republican presidents: The Democratic composite looked remarkably Clinton-like and the Republican composite bore a striking similarity to George Bush Jr. (see

fig. 5

).

fig. 5

).

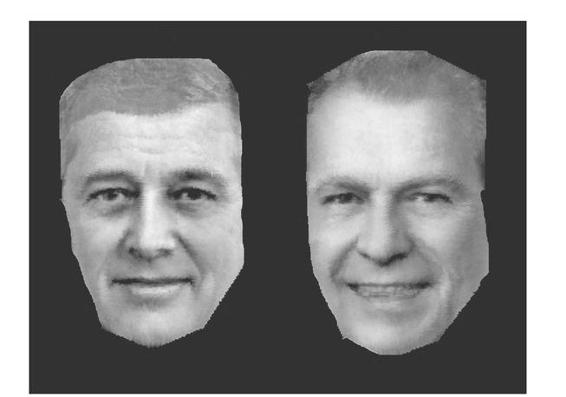

We wondered whether these results came about because the composites contained images of Bill Clinton and George Bush Jr., and so we excluded both of these faces, and re-ran the analysis.

Fig. 5

Composites of the last six Democratic (left) and Republican (right) presidents.

Composites of the last six Democratic (left) and Republican (right) presidents.

Even without Clinton and Bush, the results were almost exactly the same. The Democratic composite still looked far more Clinton than Bush, and the Republican composite was clearly more Bush than Clinton (see

fig. 6

). In short, evidence that Democratic and Republican voters are drawn to leaders that conform to very different facial “types.”

fig. 6

). In short, evidence that Democratic and Republican voters are drawn to leaders that conform to very different facial “types.”

Were these differences really driven by Democrats’ attraction to faces that appear more liberally orientated and Republicans’ preferences for more authoritarian types? To find out, we asked a group of people to rate the faces shown in

figure 6

. For each face, they were presented with various adjectives, such as “caring,” and “authoritarian,” and asked to indicate whether they believed that the person shown in the photograph possessed that trait. They had no idea that the faces were based on presidents, or that the experiment was even related to the psychology of voting. Even so, large differences emerged. The Republican composite was rated as significantly more authoritarian than the Democratic composite, and the Democratic composite was seen as far more caring and open-minded than the Republican one.

figure 6

. For each face, they were presented with various adjectives, such as “caring,” and “authoritarian,” and asked to indicate whether they believed that the person shown in the photograph possessed that trait. They had no idea that the faces were based on presidents, or that the experiment was even related to the psychology of voting. Even so, large differences emerged. The Republican composite was rated as significantly more authoritarian than the Democratic composite, and the Democratic composite was seen as far more caring and open-minded than the Republican one.

Fig. 6

Composites of the last six Democratic (left) and Republican (right) presidents, excluding Bill Clinton and George Bush Jr.

Composites of the last six Democratic (left) and Republican (right) presidents, excluding Bill Clinton and George Bush Jr.

Even when it comes to one of the most important and powerful political positions in the world, voters do indeed appear to ask themselves a key question: Does the face fit?

If facial stereotypes can influence winning or losing at the ballot box, are there other situations where looks matter? Could these same types of stereotypes even influence whether people determine the guilt of defendants in a courtroom?

In chapter 2, I described how my first mass-media psychology experiment with the help of Sir Robin Day had explored the psychology of lying. Three years later, I went back to the same studio to conduct a second study. This time the experiment was bigger and far more complicated than before. This time we wanted to discover whether justice really is blind.

The idea for the study had occurred to me when I had come across a Gary Larson

Far Side

cartoon. The cartoon was set in a courtroom, and the lawyer was talking to the jury. Pointing at his client, the lawyer said, “And so I ask the jury . . . is that the face of a mass murderer?” Sitting in the dock is a man wearing a suit and tie, but instead of a normal head, he has the classic “smiley” face consisting of just two black dots for eyes and a large semicircle grin. Like all good comedy, Larson’s cartoon made me laugh, but then it made me think.

Far Side

cartoon. The cartoon was set in a courtroom, and the lawyer was talking to the jury. Pointing at his client, the lawyer said, “And so I ask the jury . . . is that the face of a mass murderer?” Sitting in the dock is a man wearing a suit and tie, but instead of a normal head, he has the classic “smiley” face consisting of just two black dots for eyes and a large semicircle grin. Like all good comedy, Larson’s cartoon made me laugh, but then it made me think.

The decisions made by juries have serious implications, and so it is important that they are as rational as possible. I thought it would be interesting to put this alleged rationality to the test. During a live edition of the BBC’s leading science program,

Tomorrow’s World,

the members of the public were asked to play the roles of jury members. They were shown a film of a mock trial, had to decide whether the defendant was guilty or innocent, and then record their decisions by telephoning one of two numbers.

Tomorrow’s World,

the members of the public were asked to play the roles of jury members. They were shown a film of a mock trial, had to decide whether the defendant was guilty or innocent, and then record their decisions by telephoning one of two numbers.

Unbeknownst to them, we would cut the country into two huge groups. We discovered that the BBC broadcasts to the nation via thirteen separate transmitters. Usually they all carry an identical signal, so the whole of the country watches the same program. However, for this experiment, we obtained special permission to send out different signals from the transmitters, allowing me to split Britain in two and to broadcast different programs to each half of the country.

Everyone saw exactly the same evidence about a crime in which the defendant had allegedly broken into a house and stolen a computer. However, half the public saw a defendant whose face showed characteristics of the stereotype of a criminal—he had a broken nose and close-set eyes. The other half saw a defendant whose face matched a stereotypical innocent person—he was baby-faced and had clear blue eyes. To ensure that the experiment was as well controlled as possible, both defendants were dressed in identical suits, stood in exactly the same position in the dock, and had the same neutral expression on their faces.

We carefully scripted a judge’s summing-up, describing how the defendant had been accused of a burglary. The evidence presented did not allow for a clear guilty or not guilty decision. For example, the defendant’s wife said that he was in a bar at the time of the crime, but another witness saw him leave about thirty minutes before the burglary. A footprint at the scene of the crime matched the defendant’s shoes, but these were a fairly common brand of shoe owned by many people.

After transmission, we stood anxiously by the telephones and waited to see how many calls we would receive. The experiment had obviously struck a chord with the public. For the lying experiment we had received about 30,000 calls. This time, more than twice as many people telephoned. A fair and rational public would have focused solely on the evidence when deciding guilt or innocence. However, the unconscious tendency to succumb to the lure of looks proved too much. About 40 percent returned a guilty verdict on the man who just happened to fit the stereotype of a criminal. Only 29 percent found the blue-eyed, baby-faced man guilty. People had ignored the complexity of the evidence and made up their minds on the basis of the defendants’ looks.

It would be nice to think that this result is confined to the relatively artificial setting of a television studio. That is not, however, the case. John Stewart, a psychologist from Mercyhurst College in Arizona, spent hours sitting in courts rating the attractiveness of real defendants.

41

He discovered that good-looking men were given significantly lighter sentences than their equally guilty, but less attractive, counterparts.

41

He discovered that good-looking men were given significantly lighter sentences than their equally guilty, but less attractive, counterparts.

Other books

Earth Strike by Ian Douglas

The Apprentices (The Crimson Guard Trilogy Book 1) by Journey, Dana

One Hot Winter's Night by Woods, Serenity

Slave Next Door by Bales, Kevin, Soodalter, Ron.

Claimed by the Alphas: Part Five by Rivard, Viola

Judas Burning by Carolyn Haines

When You Are Mine by Kennedy Ryan

Labyrinth of Night by Allen Steele

Longing for Home by Kathryn Springer

Jaxson's Song by Angie West