QI: The Book of General Ignorance - the Noticeably Stouter Edition (9 page)

Read QI: The Book of General Ignorance - the Noticeably Stouter Edition Online

Authors: John Lloyd,John Mitchinson

Tags: #Humor, #General

No, although this is a relatively recent insight.

For hundreds of years people thought the feathery-legged shellfish were the embryos of geese. Because these geese breed in the Arctic Circle no one had seen them mate or lay eggs. When they flew south in the autumn, by complete coincidence, barnacle-laden driftwood also blew ashore. Some bright spark spotted this and made the connection.

The Latin for Irish goose is

Anser hiberniculae

, Hibernia being the Roman name for Ireland. This was shortened to bernacae and by 1581 ‘barnacle’ was used for both the geese and the shellfish. The confusion was widespread and persistent.

This caused problems for the Irish Church. Some dioceses allowed the eating of geese on fast days because they were a kind of fish, others because they came from a bird-bearing tree, and were ‘not born of the flesh’, and therefore a kind of vegetable or nut. Others didn’t, so papal intervention was required. Pope Innocent III finally banned goose-eating on fast days in 1215.

Four hundred years later, the Royal Society still carried accounts of wood laden with ‘shells carrying the embryos of geese’ and even Linnaeus gave some credence to the legend by naming two species of barnacle

Lepas anatifera

(duck-bearing shellfish) and

Lepas anserifera

(goose-bearing shellfish).

Abiogenesis, the idea that living creatures arise from nonliving matter, was one of the less useful legacies of Aristotle. Despite the work of seventeenth-century scientists like van Leeuwenhoek and Francesco Redi showing that all living creatures, however small, reproduce, the theory persisted well into the nineteenth century. It wasn’t until Pasteur showed that even bacteria reproduce that the idea of ‘spontaneous generation’ could finally be thrown out.

The seventeenth century, surely? It’s about the plague: the rings of roses are skin lesions, the first signs of infection; the posies are the doomed attempts to keep the disease at bay; the sneezing is a symptom of the advancing sickness; ‘all fall down’ is death.

Like most attempts to attribute precise historical meaning to nursery rhymes this doesn’t hold water. It was first advanced in 1961 by the popular novelist James Leasor in his racy account of life in seventeenth-century London,

The Plague and the Fire

. Until then, there was no obvious connection (and absolutely no evidence) that the rhyme had been sung in this form for almost 400 years as a way of preserving the trauma of the plague.

That’s because it hadn’t. The very earliest recorded version comes from Massachusetts in 1790:

Ring a ring a rosie

A bottle full of posie,

All the girls in our town

Ring for little Josie.

There are French, German and even Gaelic versions. Several have a second verse where everyone gets up again; others mention wedding bells, pails of water, birds, steeples, Jacks, Jills and other favourite nursery images.

A more credible theory is that the rhyme grew out of a ring game, a staple element of the ‘play-parties’ which had grown up in Protestant communities in eighteenth-century America and Britain where dancing was forbidden.

‘Ring-a-ring o’ roses’ remains our most popular ring game today.

Henry Bett in his 1924 collection of

Nursery Rhymes and Tales

took the view that the rhyme is of an age ‘to be measured in

thousands of years, or rather it is so great it cannot be measured at all.’

‘Drink, drink. Fan, fan. Rub, rub.’

These were the absolutely last things the dying admiral said. He was hot and thirsty. His steward stood by to fan him and feed him lemonade and watered wine, while the ship’s chaplain, Dr Scott, massaged his chest to ease the pain.

Historians are certain that Nelson did indeed say ‘Kiss me, Hardy’ rather than, as some have suggested, the more noble ‘Kismet’ (meaning fate). Eyewitnesses testified that Hardy kissed the admiral twice: once on the cheek and once on the forehead, as Nelson struggled to remain conscious.

Nelson asked his flag-captain not to throw him overboard and to look after ‘poor Lady Hamilton’. He then uttered the immortal words. After Hardy’s first kiss he said, ‘Now I am satisfied.’ After the second, ‘Who is that?’ When he saw it was Hardy he croaked, ‘God bless you, Hardy.’

Shortly afterwards he muttered, ‘Thank God I have done my duty’ and then ‘Drink, drink. Fan, fan. Rub, rub.’ He lost consciousness, the surgeon was called and Nelson was declared dead at 4.30 p.m.

It seems that Nelson had deliberately decided to die at the moment of his greatest victory at Trafalgar. For a guinea each he bought four large silver stars and had them sewn into his uniform along with the glitzy Neapolitan Order of St Ferdinand. He then stood brazenly in the middle of the deck of HMS

Victory

till he was shot at a range of fifty feet by a French sniper.

It was a comprehensive victory. Though 1,700 British sailors had been killed or wounded, no ships were lost. The French and Spanish fleets had been decimated: 18 ships captured or destroyed, 6,000 men killed or wounded and 20,000 taken prisoner. The risk of an invasion of Britain had passed. Nelson’s immortality was assured.

His body was preserved on its way back from Trafalgar in a cask of brandy. Rumour had it that, on the voyage home to England, sailors drank the contents of the barrel, using tubes of macaroni as straws. This is not the case. The barrel was kept under armed guard and, according to eyewitnesses, when it was opened in Portsmouth, seemed well topped-up.

Whether true or not, the legend stuck and the Navy adopted the phrase ‘tapping the Admiral’ for the surreptitious swigging of rum.

STEPHEN

How did Nelson keep his men’s spirits up after he died

?

JO

Did he allow Hardy to use him as a ventriloquist’s dummy

?

Neither. Nelson never wore an eye-patch.

He didn’t wear anything at all over his damaged right eye, though he had an eye-shade built into his hat to protect his good left eye from the sun.

Nelson didn’t have a ‘blind’ eye. His right one was badly damaged (but not blinded) at the siege of Calvi in Corsica in 1794. A French cannon ball threw sand and debris into it, but it still looked normal – so normal, in fact, he had difficulty convincing the Royal Navy he was eligible for a disability pension.

There is no contemporary portrait of Nelson wearing an eye-patch, and despite what most people recall having ‘seen’, the Trafalgar Square column shows him

without

an eye-patch. It was only after his death that the eye-patch was used to add pathos to portraits.

He used the damaged eye to his advantage. At the battle of Copenhagen in 1801, he ignored the recall signal issued by his superior Admiral Sir Hyde Parker. Nelson, who was in a much better position than Parker to see that the Danes were on the run, said to his flag-captain: ‘You know, Foley, I only have one eye – I have the right to be blind sometimes.’

He then held his telescope to his blind eye and said: ‘I really do not see the signal!’ This is usually misquoted as: ‘I see no ships.’

Nelson was a brilliant tactician, a charismatic leader and undeniably brave – had he been alive today he would have been eligible for at least three Victoria Crosses – but he was also vain and ruthless.

As captain of HMS

Boreas

in 1784 he ordered 54 of his 122 seamen and 12 of his 20 marines flogged – 47 per cent of the men aboard. In June 1799, he treacherously executed 99 prisoners of war in Naples, after the British commander of the garrison had guaranteed their safety.

While in Naples, Nelson began an affair with Lady Emma Hamilton, wife of the British ambassador. Her father had been a blacksmith and she a teenage prostitute in London before marrying Sir William. She was enormously fat and had a Lancashire accent. Another admirer of Nelson was Patrick Brunty, a Yorkshire parson of Irish descent, who changed his surname to Brontë after the King of Naples created Nelson Duke of Bronte. Had he not done so, his famous daughters would have been Charlotte, Emily and Anne Brunty.

In contrast to the public grief at news of Nelson’s death,

Earl St Vincent and eighteen other admirals of the Royal Navy refused to attend his funeral.

At least nine.

The five senses we all know about – sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch – were first listed by Aristotle, who, while brilliant, often got things wrong. (For example, he taught that we thought with our hearts, that bees were created by the rotting carcasses of bulls and that flies had only four legs.)

There are four more commonly agreed senses:

1

Thermoception

, the sense of heat (or its absence) on our skin.2

Equilibrioception

– our sense of balance – which is determined by the fluid-containing cavities in the inner ear.3

Nociception

– the perception of pain from the skin, joints and body organs. Oddly, this does not include the brain, which has no pain receptors at all. Headaches, regardless of the way it seems, don’t come from inside the brain.4

Proprioception

– or ‘body awareness’. This is the unconscious knowledge of where our body parts are without being able to see or feel them. For example, close your eyes and waggle your foot in the air. You still know where it is in relation to the rest of you.

Every self-respecting neurologist has their own opinion about whether there are more than these nine. Some argue that

there are up to twenty-one. What about hunger? Or thirst? The sense of depth, or the sense of meaning, or language? Or the endlessly intriguing subject of synaesthesia, where senses collide and combine so that music can be perceived in colour?

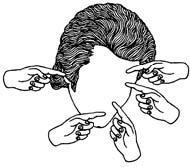

And what about the sense of electricity, or even impending danger, when your hair stands on end?

There are also senses which some animals have but we don’t. Sharks have keen

electroception

which allows them to sense electric fields,

magnetoception

detects magnetic fields and is used in the navigation systems of birds and insects,

echolocation

and the ‘lateral line’ are used by fish to sense pressure, and infrared vision is used by owls and deer to hunt or feed at night.

ALAN

What about the ‘sixth sense’

?

STEPHEN

That’s right. Yeah, it’s an old phrase, because in those days, they only thought of five senses

.

ALAN

So, what, it’d be

…

It should be the ‘twenty-second sense’

?

Three, that’s easy. Solid, liquid, gas.

Actually, it’s more like fifteen, although the list grows almost daily.

Here’s our latest best effort:

solid, amorphous solid, liquid, gas, plasma, superfluid, supersolid, degenerate matter, neutronium, strongly symmetric matter, weakly symmetric matter, quark-gluon plasma, fermionic condensate, Bose-Einstein condensate and strange matter.

Without going into impenetrable (and, for most purposes, needless) detail, one of the most curious is Bose-Einstein condensate.

A Bose-Einstein condensate or ‘bec’ occurs when you cool an element down to a very low temperature (generally a tiny fraction of a degree above absolute zero (–273 °C, the theoretical temperature at which everything stops moving).

When this happens, seriously peculiar things begin to happen. Behaviour normally only seen at atomic level occurs at scales large enough to observe. For example, if you put a ‘bec’ in a beaker, making sure to keep it cold enough, it will actually climb the sides and de-beaker itself.

This, apparently, is a futile attempt to reduce its own energy (which is already at its lowest possible level).

Bose-Einstein condensate was predicted to exist by Einstein in 1925, after studying the work of Satyendra Nath Bose, but wasn’t actually manufactured until 1995 in America – work that earned its creators the 2001 Nobel Prize. Einstein’s manuscript itself was only rediscovered in 2005.