QI: The Book of General Ignorance - the Noticeably Stouter Edition (31 page)

Read QI: The Book of General Ignorance - the Noticeably Stouter Edition Online

Authors: John Lloyd,John Mitchinson

Tags: #Humor, #General

Algae.

They release oxygen as a waste-product of photosynthesis. Their net oxygen output is higher than that produced by all the trees and other land-based plants put together.

Ancient algae are also the main constituent of oil and gas.

Blue-green algae or cyanobacteria (from Greek

kyanos

– ‘dark greeny blue’) is Earth’s earliest known life form, with fossils that date back 3.6 billion years.

While some algae are included with the plants in the Eukaryote domain (

eu

, ‘true’, and

karyon

, ‘nut’, referring to their cells having true nuclei, which bacteria don’t), the cyanobacteria are now firmly in the Bacteria kingdom, with their own phylum.

One form of cyanobacteria, spirulina, yields twenty times more protein per acre than soya beans. It consists of 70 per cent protein (compared with beef’s 22 per cent), 5 per cent fat, no cholesterol and an impressive array of vitamins and minerals. Hence the increasing popularity of the spirulina smoothie.

It also boosts the immune system, particularly the production of protein interferons, the body’s front-line defence against viruses and tumour cells.

The nutritional and health benefits of spirulina were recognised centuries ago by the Aztecs, sub-Saharan Africans and flamingos.

Its significance for the future may be that algae can be grown on land that isn’t fertile, using (and recycling) brackish water. It’s a crop that doesn’t cause soil erosion, requires no fertilisers or pesticides and refreshes the atmosphere more than anything else that grows.

ALAN

I’ve got it [algae] in my pond. I get rid of it.

STEPHEN

Think how many people you’ll kill by doing that. You might

just as well go around with a pillow and clamp them to old ladies’ faces.

Nettles.

During the First World War, both Germany and Austria ran short on supplies of cotton.

In search of a suitable replacement, scientists chanced upon an ingenious solution: mixing very small quantities of cotton with nettles – specifically, the hardy fibres of the stinging nettle (

Urtica dioica

).

Without any form of systematic production, the Germans cultivated 1.3 million kg of this material in 1915, and a further 2.7 million kg the following year.

After a brief struggle, the British captured two German overalls in 1917, and their construction was analysed with some surprise.

Nettles have many advantages over cotton for agriculture – cotton needs a lot of watering, it only grows in a warm climate, and requires a lot of pesticide treatment if it is to be grown economically.

There’s no danger of being stung by a ‘full nettle jacket’ either, as the stinging hairs – little hypodermic syringes made of silica and filled with poison – are not used in production. The long fibres in the stems are all that are useful.

The Germans were by no means the first to stumble across this plant’s many uses. Archaeological remains from around Europe reveal that it’s been used for tens of thousands of

years for fishing nets, twine and cloth.

The Bottle Inn, a pub in Marshwood, Dorset, England, holds an annual World Stinging Nettle Eating Championship. Rules are strict: no gloves, no mouth-numbing drugs (other than beer) and no regurgitation.

The trick appears to be to fold the top of the nettle leaf towards you and push it past your lips before swigging it down with ale. A dry mouth, they say, is a sore mouth. The winner is the one who has the longest set of bare stalks at the end of an hour.

The current record is 14.6 m (48 feet) for men, and about 8 m (26 feet) for women.

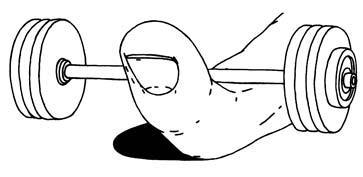

The human hand: the crew of the carrier simply reached up and pulled the plane down out of the air.

The world’s first landing by an aeroplane on to a ship under way at sea was made on 2 August 1917 by Squadron Commander Edwin Harris Dunning,

DSC

,

RN

, in a Sopwith Pup on to the hanger roof of the converted battlecruiser HMS

Furious

.

Dunning worked out that by combining the 40-knot stalling speed of the plane, the 21-knot top speed of the ship and a 19-knot wind he could hover relative to the ship. So, while

Furious

steamed into the wind, Dunning flew past it as close as possible, drifted round the bridge until he arrived over the roof of the hanger, side-slipped and pulled back on the throttle, allowing the plane to sink towards the deck. At this, a

party of officers and men rushed out and grabbed the specially prepared ropes dangling from the plane and pulled it down on to the roof.

Dunning completed a second landing in this way before deciding it was not a practical procedure. Five days later, he took off again, having given instructions that his plane was not to be touched until it had come to a complete standstill. But this time, when he arrived over the hanger, something went horribly wrong. Either he touched down and one of his tyres burst or he pulled back too hard on the throttle and the plane stalled. At any rate it swerved, the wind blew the aircraft over the side and the pilot was knocked unconscious and drowned.

HMS

Furious

was one of a trio of battle cruisers built during World War I, the other two being the

Courageous

and the Glorious. Said to be the most ludicrous warships ever built for the Royal Navy, they were known throughout the Fleet as the

Spurious

, the

Outrageous

and the

Uproarious

.

Furious

was designed with two 46-cm (18-inch) gun turrets fore and aft. At the time, these were the largest guns in the world.

The reference to the human hand as a ‘sophisticated mechanism’ is not intended to be sarcastic. In

How

The Mind Works

, Stephen Pinker (noting that it was first pointed out by the Roman physician Galen 2,000 years ago) shows what an astonishing piece of engineering the human hand represents. Each one does the job of at least ten different tools. He names a hook grip (to lift a bucket); a scissor grip (to hold a cigarette); a five-jaw chuck (to lift a coaster); a three-jaw chuck (to hold a pencil); a two-jaw pad-to-pad chuck (to thread a needle); a two-jaw pad-to-side chuck (to turn a key); a squeeze grip (to hold a hammer); a disc grip (to open a jar); and a spherical grip (to hold a ball). Numerous other tools could be cited including a screwdriver, a weighing machine and a surface sensor.

Amazingly, the answer is none at all.

The muscles that control your fingers are all in your arm. Your fingers are moved like puppets on a string, the strings being the tendons controlled by the muscles of the forearm.

Try drumming your fingers and watch the skin on your forearm ripple. Or place your hand on the table as if you were doing an impression of a spider with straight legs, tuck your middle finger under your hand and then try to lift each finger in turn. You’ll find that you can’t lift your ring finger, because the tendons in your fingers are all independent of each other, except for the one controlling the middle and ring fingers, which is shared between the two.

An extreme pedant might point out that there are actually thousands of muscles in each finger, if you count the tiny retractors that cause your hairs to stand up or your blood vessels to contract, but these don’t move the fingers.

A commonly repeated factoid is that the tongue is the strongest muscle in the human body. This is plain wrong, not least because the tongue comprises sixteen separate muscles, not one, but even taken together they aren’t the strongest, no matter which definition of strength one uses. The strongest muscle is either the largest (here the contenders are the gluteus maximus that makes up most of your buttocks or the quadriceps in your thigh) or the one that can exert most pressure on an object (which is your jaw muscle).

However, probably the strongest ‘pound for pound’ muscle

is the uterus: it weighs around 2 pounds (just under a kilogram) but during childbirth can exert a downward force of 400 Newtons, which is one hundred times as strong as gravity and equivalent to the power in a fully extended modern longbow.

Sir Alexander Fleming is a long way down the list.

Bedouin tribesmen in North Africa have made a healing ointment from the mould on donkey harnesses for over a thousand years.

In 1897, a young French army doctor called Ernest Duchesne rediscovered this by observing how Arab stable boys used the mould from damp saddles to treat saddle sores.

He conducted thorough research identifying the mould as

Penicillium glaucu

m

, used it to cure typhoid in guinea pigs and noted its destructive effect on

E. coli

bacteria. It was the first clinically tested use of what came to be called penicillin.

He sent in the research as his doctoral thesis, urging further study, but the Institut Pasteur didn’t even acknowledge receipt of his work, perhaps because he was only twenty-three and a completely unknown student.

Army duties intervened and he died in obscurity in 1912 of tuberculosis – a disease his own discovery would later help to cure.

Duchesne was posthumously honoured in 1949, five years after Sir Alexander Fleming had received his Nobel Prize for his re-rediscovery of the antibiotic effect of penicillin.

Fleming coined the word ‘penicillin’ in 1929. He accidentally noticed the antibiotic properties of a mould

which he identified as

Penicillium rubrum

. In fact, he got the species wrong. It was correctly identified many years later by Charles Thom as

Penicillium notatum

.

The mould was originally named

Penicillium

because, under a microscope, its spore-bearing arms were thought to look like tiny paintbrushes. The Latin for a writer’s paintbrush is

penicillum

, the same word from which ‘pencil’ comes. In fact, what the mould cells of

Penicillium

notatum

much more closely and spookily resemble is the hand-bones of a human skeleton. There is a picture of it here:

http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/Toms_fungi/nov2003.html

Stilton, Roquefort, Danish Blue, Gorgonzola, Camembert, Limburger and Brie all contain penicillin.