QI: The Book of General Ignorance - the Noticeably Stouter Edition (18 page)

Read QI: The Book of General Ignorance - the Noticeably Stouter Edition Online

Authors: John Lloyd,John Mitchinson

Tags: #Humor, #General

It has nothing to do with archery.

The oldest definite record of someone using a V-sign only dates back as far as 1901, when there is documentary footage of a young man who clearly didn’t want to be filmed using the gesture to camera outside an ironworks in Rotherham. This proves that the gesture was being used by the late nineteenth century, but it’s a long way from the bowmen at the Battle of Agincourt.

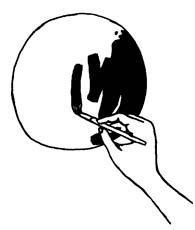

According to the legend, English archers waved their fingers in contempt at their French counterparts, who were supposed to be in the habit of cutting off the fingers of captured

bowmen – a fingerless archer being useless, as he could not draw back the string.

Although one historian claims to have unearthed an eyewitness account of Henry V’s pre-battle speech that refers to this French practice, there is no contemporary evidence of the V-sign being used in the early fifteenth century. Despite there being a number of chroniclers present at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415, none of them mentions any archers using this defiant gesture. Secondly, even if archers were captured by the French they were much more likely to be killed rather than be subject to the fiddly and time-consuming process of having their fingers amputated. Prisoners were usually only taken to be ransomed and bowmen were considered inferior merchandise who wouldn’t fetch a decent price. Finally, there are no known references of any kind to the Agincourt story that date back further than the early 1970s.

What is certain is that the one-fingered ‘middle-finger salute’ dates back much further than the V-sign; it is obviously a phallic symbol – the Romans referred to the middle finger as the

digitus impudicus

, or lewd finger. In Arabic society, an upside-down version of ‘flicking the bird’ is used to signify impotence.

Whatever its date of origin, the V-sign wasn’t universally understood until quite recently. When Winston Churchill first began to use the V-for-Victory salute the wrong way round in 1940, he had to be gently told that it was rude.

No, they didn’t.

Arguably the most influential feminist protest in history

occurred at the 1968 ‘Miss America’ beauty contest in Atlantic City, New Jersey.

A small group of protesters picketed the pageant with provocative slogans such as ‘Let’s Judge Ourselves as People’ and ‘Ain’t she sweet; making profits off her meat’.

They produced a live sheep which they crowned ‘Miss America’ and then proceeded to toss their high-heeled shoes, bras, curlers and tweezers into a ‘Freedom Trash Can’.

What they didn’t do was burn their bras. They wanted to, but the police advised that it would be dangerous while standing on a wooden boardwalk.

The myth of the bra-burning began with an article by a young

New York

Post

journalist called Lindsay Van Gelder.

In 1992, she told Ms. magazine: ‘I mentioned high in the story that the protesters were planning to burn bras, girdles and other items in a freedom trash can… The headline writer took it a step further and called them “bra-burners”.’

The headline was enough. Journalists across America seized on it without bothering to even read the story. Van Gelder had created a media frenzy.

Even scrupulous publications such as the

Washington Post

were caught out.

They identified members of the National Women’s Liberation Group as the same women who ‘burned undergarments during a demonstration at the Miss America contest in Atlantic City recently.’

The incident is now used as a textbook case in the study of how contemporary myths originate.

a

)

Black with silvery bits

b

)

Silver with black bits

c

)

Pale green

d

)

Beige

It’s officially beige.

In 2002, after analysing the light from 200,000 galaxies collected by the Australian Galaxy Redshift Survey, American scientists from Johns Hopkins University concluded that the universe was pale green. Not black with silvery bits, as it appears. Taking the Dulux paint range as a standard, it was somewhere between Mexican Mint, Jade Cluster and Shangri-La Silk.

A few weeks after the announcement to the American Astronomical Society, however, they had to admit they’d made a mistake in their calculations, and that the universe was, in fact, more a sort of dreary shade of taupe.

Since the seventeenth century, some of the greatest and most curious minds have wondered why it is that the night sky is black. If the universe is infinite and contains an infinite number of uniformly distributed stars, there should be a star everywhere we look, and the night sky should be as bright as day.

This is known as Olbers’ Paradox, after the German astronomer Heinrich Olbers who described the problem (not for the first time) in 1826.

Nobody has yet come up with a really good answer to the problem. Maybe there is a finite number of stars, maybe the light from the furthest ones hasn’t reached us yet. Olbers’ solution was that, at some time in the past, not all the stars had been shining and that something had switched them on.

It was Edgar Allan Poe, in his prophetic prose poem

Eureka

(1848), who first suggested that the light from the most distant stars is still on its way.

In 2003, the Ultra Deep Field Camera of the Hubble Space Telescope was pointed at what appeared to be the emptiest piece of the night sky and the film exposed for a million seconds (about eleven days).

The resulting picture showed tens of thousands of hitherto unknown galaxies, each consisting of hundreds of millions of stars, stretching away into the dim edges of the universe.

JEREMY HARDY

It’s deceptive, the universe, ’cause from the outside, if you’re God, it looks quite small. But when you’re in there, it’s really quite spacious, with plenty of storage.

Butterscotch.

Or brown. Or orange. Maybe khaki with pale pink patches.

One of the most familiar features of the planet Mars is its red appearance in the night sky. This redness, however, is due to the dust in the planet’s atmosphere. The surface of Mars tells a different story.

The first pictures from Mars were sent back from Viking I, seven years to the day after Neil Armstrong’s famous moon landing. They showed a desolate red land strewn with dark rocks, exactly what we had expected.

This made the conspiracy theorists suspicious: they

claimed that NASA had deliberately doctored the pictures to make them seem more familiar.

The cameras on the two Viking rovers that reached Mars in 1976 didn’t take colour pictures. The digital images were captured in grey-scale (the technical term for black and white) and then passed through three colour filters.

Adjusting these filters to give a ‘true’ colour image is extremely tricky and as much an art as a science. Since no one has ever been to Mars, we have no idea what its ‘true’ colour is.

In 2004, the

New York Times

stated that the early colour pictures from Mars were published slightly ‘over-pinked’, but that later adjustments showed the surface to be more like the colour of butterscotch.

NASA’s Spirit rover has been operating on Mars for the past two years. The latest published pictures show a greeny-brown, mud-coloured landscape with grey-blue rocks and patches of salmon-coloured sand.

We probably won’t know the ‘real’ colour of Mars until someone goes there.

In 1887, the Italian astronomer Giovanni Schiaparelli reported seeing long straight lines on Mars which he called

canali

, or ‘channels’. This was mistranslated as ‘canals’, starting rumours of a lost civilisation on Mars.

Water is thought to exist on Mars in the form of vapour, and as ice in the polar ice caps, but since more powerful telescopes have been developed, no evidence of Schiaparelli’s ‘canals’ has ever been found.

Cairo, or al-Qāhirah, is Arabic for Mars.

The usual answer it that it isn’t any colour; it’s ‘clear’ or ‘transparent’ and the sea only appears blue because of the reflection of the sky.

Wrong. Water really is blue. It’s an incredibly faint shade, but it is blue. You can see this in nature when you look into a deep hole in the snow, or through the thick ice of a frozen waterfall. If you took a very large, very deep white pool, filled it with water and looked straight down through it, the water would be blue.

This faint blue tinge doesn’t explain why water sometimes takes on a strikingly blue appearance when we look

at

it rather than

through

it. Reflected colour from the sky obviously plays an important part. The sea doesn’t look particularly blue on an overcast day.

But not all the light we see is reflected from the surface of the water; some of it is coming from under the surface. The more impure the water, the more colour it will reflect.

In large bodies of water like seas and lakes the water will usually contain a high concentration of microscopic plants and algae. Rivers and ponds will have a high concentration of soil and other solids in suspension.

All these particles reflect and scatter the light as it returns to the surface, creating huge variation in the colours we see. It explains why you sometimes see a brilliant green Mediterranean sea under a bright blue sky.

Bronze. There is no word for ‘blue’ in ancient Greek.

The nearest words –

glaukos

and

kyanos

– are more like expressions of the relative intensity of light and darkness than attempts to describe the colour.

The ancient Greek poet Homer mentions only four actual colours in the whole of the

Iliad

and the

Odyssey

, roughly translated as black, white, greenish yellow (applied to honey, sap and blood) and purply red.

When Homer calls the sky ‘bronze’, he means that it is dazzlingly bright, like the sheen of a shield, rather than ‘bronze-coloured’. In a similar spirit, he regarded wine, the sea and sheep as all being the same colour – purply red.

Aristotle identified seven shades of colour, all of which he thought derived from black and white, but these were really grades of brightness, not colour.

It’s interesting that an ancient Greek from almost 2,500 years ago and NASA’s Mars rovers of 2006 both approach colour in the same way.

In the wake of Darwin, the theory was advanced that the early Greeks’ retinas had not evolved the ability to perceive colours, but it is now thought they grouped objects in terms of qualities other than colour, so that a word which seems to indicate ‘yellow’ or ‘light green’ really meant fluid, fresh and living, and so was appropriately used to describe blood, the human sap.

This is not as rare as you might expect. There are more languages in Papua New Guinea than anywhere else in the world but, apart from distinguishing between light and dark, many of them have no other words for colour at all.

Classical Welsh has no words for ‘brown’, ‘grey’, ‘blue’ or ‘green’. The colour spectrum is divided in a completely different way. One word (

glas

) covered part of green; another the rest of green, the whole of blue and part of grey; a third dealt with the rest of grey and most, or part, of brown.

Modern Welsh uses the word

glas

to mean blue, but Russian has no single word for ‘blue’. It has two –

goluboi

and

sinii

–

usually translated ‘light blue’ and ‘dark blue’, but, to Russians, they are distinct, different colours, not different shades of the same colour.

All languages develop their colour terms in the same way. After black and white, the third colour to be named is always red, the fourth and fifth are green and yellow (in either order), the sixth is blue and the seventh brown. Welsh still doesn’t have a word for brown.

ALAN

I’ve got no time for these Greeks.

STEPHEN

And yet without them, you wouldn’t be here.

ALAN

Oh, that’s so rubbish! [hitting desk with palm of hand] You say this every week!