Q: A Novel (15 page)

Authors: Evan Mandery

It’s a bad situation, but for once I am on the right side of it, which is neither. This is primarily because I do not understand the debate. I don’t admit this, of course. My public position is that I support Hank Snjdon and his efforts to mediate a compromise. Hank is grateful for my backing, so when I go to see him to talk about my own situation, I am not surprised that he is reciprocally supportive.

“I’m thinking of doing a book on Freud,” I say.

“Great,” he says.

“My five-year review is coming up. I’m worried about tenure.”

“Why? Everyone likes Freud.”

“It’s another novel. It’s about what would have happened if he had published his discovery of eel testes and made an impression in the scientific community.”

“Freud studied eel testes? Really?”

“Really.”

Hank shakes his head. “You can’t just make this stuff up. What would Freud have to say about that?” We both laugh.

“Seriously, though,” I say when the guffaws die down. “I think it’s a valid counterhistorical question. I believe that if Freud had experienced success with his eel research he would have become a biologist. Ultimately, I believe he would have fundamentally changed the popular understanding of evolution.”

“That’s interesting. Why would Freud have reached a different conclusion than anyone else?”

“He was utterly nonjudgmental,” I say. “I think he was uniquely suited to understand Charles Darwin’s true meaning.”

“Which was?”

“That evolution has no purpose.”

Hank chewed on this for a while, though it might also have been a Mentos. He really liked Mentos mints. When the cinnamon ones went off the market, he was sad for weeks.

“I’m confused about one thing,” Hank says after a while. “If Freud found the eel testes, as you say, why didn’t he publish the discovery?”

“I don’t know. I need to figure that out. Or at least to come up with a plausible revision of his life that would have emboldened him to publish his true results. What do you think of the idea otherwise?”

“I think it is fine.”

“But this will be my second novel, and this is a history department.”

Hank thinks for a moment.

“What you are writing could have been true, right?”

“Yes,” I say. “The kernel is true though the rest of it isn’t.”

“I think the distinction between ‘is’ and ‘might have been’ is generally overblown.” So, with Hank Snjdon’s blessing, it is full steam ahead. I begin writing the next day.

The creative process

is a mystery to me. I want to understand how it works, like the physics of the golf swing. I would settle for feeling the critical moment when the germ of an idea is formed, but I rarely experience even this. Sometimes I have ideas while I am running. Sometimes I have ideas while I am eating cereal. I conceived of the final scene of

Time’s Broken Arrow

—in which William Henry Harrison tenderly drapes an overcoat over the shoulders of his friend and successor, Daniel Webster, midway through Webster’s own inaugural address—following a comalike nap during the second act of

Don Giovanni

. Generally, I have no idea when the ideas will come, or how. It is all a bit magical.

I once heard James Taylor say in an interview that he does not write songs, that he is simply the first to hear them. This is how I feel about it. Somehow, five hours after I sit down to work, words have appeared on the page, grossly imperfect to be sure, but something where there was nothing. I view my role in this miracle of creation as showing up at my desk, sitting upright at my computer, and staying out of the way of my brain. All I ask in return is that I have something to show for my efforts at the end of the day, that there be progress.

My routine is to get up early, eat a small breakfast, and write from seven o’clock until noon. I find that after lunch I am mostly useless, so I try to get as much done in the morning as I possibly can. In the afternoons I answer emails, edit what I have written in the morning, and, on Thursdays, teach my freshman seminar on cultural history. Then I take a run, have dinner, and get to bed early so I can do it all again the next day. I repeat this seven days a week.

It is a lonely process. Writing is occasionally exciting; epiphanies sometimes occur. But for the most part, it is a monotonous, plodding endeavor. And this is a particularly desolate time. The excitement of

Time’s Broken Arrow

has passed. Leonard Lopate is not calling. No one stops me on the street to ask for autographs.

And, of course, Q is gone.

Every writer

(except, notably, Pynchon) lives for the moment when he is uncloistered, unbound from the invisible tether to his computer, and allowed to favor the world with his razor wit and profound insight into the meaning of life. I hope that I will enjoy such a moment again, but the reality has set in that this glory is far off in the distance. As a runner, I view writing a book as a marathon. If that metaphor is apt, I am in mile five. How much remains is daunting.

Furthermore, the selection of Freud as a subject means the book serves as a near-constant reminder of the choices I have made in my own life. Freud was fiercely lonely during his time in Trieste. He spent long hours laboring in front of the microscope and detailing his elegant pencil sketches. With no friends to comfort him, he did little socializing. In the evenings, after concluding work at the laboratory, he walked home, ate a small dinner, and wrote letters to Gisela Fluss, his first romantic interest. It is all too easy for me to channel Freud’s loneliness. In fact it takes nothing.

But, maddeningly, Hank Snjdon’s question remains unanswered. Six months into the project, I still cannot understand how a man who would soon become the most provocative mind of his generation would have felt impelled to do whatever necessary to advance his career, including tailoring the results of his research to support the claims of his adviser and benefactor. If he were capable of this, what could possibly have emboldened him to be a different person?

James Taylor says

that if he weren’t a musician, he’d be a fish farmer. But really, he says, he’d be lost.

The answer to

the Freud puzzle comes to me at the most unlikely time. After half a year of procrastination, I arrange to collect my few remaining things from Q and thus close the matter once and for all. We set it up so that she will not be there. I go with a heavy heart and trepidation, but with her characteristic grace, Q makes it easy. She leaves a key for me with the doorman, leaves my things neatly folded and arranged in a pile, and even leaves me a small gift.

Q makes it as painless as it possibly can be, but standing in that apartment, where Q and I shared peanut brittle while watching

Casablanca

, and completed the Sunday crossword puzzle with jam-covered toothpicks, and made snow angels in a pile of sugar on the hardwood floor, and first made love, I am overwhelmed with emotion and a sense of possibility. In this moment I want to throw away the counterhistorical novels of Freud the evolutionist and Gandhi the cricketer and even the true history of the sand wedge. Instead I want to write poetry, soaring verse worthy of Byron and Yeats, the sort that makes women swoon and quiets the most restless soul. I want to wait for Q to return home, sweep her off her feet, fly to Buenos Aires, dance the tango until midnight, then pitch a tent on Mar del Plata and live on plantains and rum, forget about John Deveril and his skyscrapers, and not return until Q and I are good and old.

Of course this cannot happen. But it offers the answer to what was missing in Freud’s life: love. For Freud certainly does not love Fluss. She gives him little comfort. He gives her the nickname of a reptile. And while he later loves Martha Bernays, the svelte and pale daughter of a merchant who becomes his wife, even the most insensitive clod can see that it is the love of a boy, not a man. During their five-year engagement, he was overridden by jealousy, which extended to Bernays’s mother and brother. By all accounts Freud and Bernays did not have conjugal relations prior to their nuptials. And the marriage, though successful in its longevity (they had been married more than fifty years when Freud died in 1939) and its productivity (the Freuds had five children, including one psychoanalyst of independent renown), did not ever produce epic passion. The couple went long periods without sex, and late in life, according to Carl Jung, Freud took up with Martha’s sister Minna, who looked more or less like Martha. The ultimate what-if, the impetus that would have made him boldly change the course of his own life, is what if Freud had fallen madly and truly head over heels in love.

I take Q’s gift and close the door behind me, careful to leave things as they were before, as if this is possible. I return home with my memories and a pear and Freud in love in Trieste. I have a direction, but I am not satisfied and, later, not surprised when I find in my mailbox another note from myself. It says:

Nobu

Thursday

6:00

G

etting a table at Jean-Georges is challenging. Getting a table at Nobu on a Friday night is nearly impossible. Once more, I call on the services of my great friend Ard Koffman, and again he delivers. I am even spared interacting with a reservationist.

I arrive at the restaurant on time. My older self is seated already, at a corner table near the waterfall, just behind one of the indoor bamboo trees. This version of me is younger than the last one. He looks to be in his mid-fifties. The years have been easier on him than they were on I-60. I-60 had canals under his sad eyes and flaky skin. He moved stiffly, as if grief burdened his every movement; even the simple extension of an arm seemed to be a cause of pain. This me is more supple. He is plumper and appears well oiled. When he rises to greet me, the movement of his arm is lithe and easy. His face is unwrinkled, almost preternaturally so, and I wonder for a moment, with horror, whether I have had some work. I take his hand, shake, and sit down, with substantial trepidation.

“Hey,” says the old me.

“Hey,” I repeat gingerly. The word isn’t ordinarily part of my lexicon.

“I suppose you’re wondering what I’m doing here.”

“The thought occurred to me,” I say. “How old are you?”

“Fifty-five,” he says. “How much time has passed from your perspective since you were last visited?”

“Six months,” I say.

I-55 shakes his head. “I’ll never forget that day in Rhinebeck,” he says wistfully.

“Me neither.”

“Do you wish you had made a different decision?”

“Every day, but what choice did I really have? What about you?”

I-55 thinks for a moment then shakes his head. “No, I don’t think I had any choice either.”

“So you have no regrets?”

“I wouldn’t say that exactly.”

The waiter arrives.

I order the sushi dinner and a Diet Coke with lemon. I-55 orders the Kumamoto oysters with Maui onion salsa, the sashimi tacos, a bottle of hot sake, a Diet Coke with lime, and finally, two skewers of squid kushiyaki.

“Two drinks?”

“I’m thirsty.”

“Two appetizers?”

“What could be more appealing than an appetizer?” I-55 asks rhetorically. “It’s inherent in the name. Two appetizers means that you enjoy the dinner twice as much. Besides,” he says, “I haven’t eaten here in ages. If I have learned one thing over the years, it is to live life for the moment. I plan on enjoying this meal to the fullest.”

“I thought time travel was bad for the appetite.”

“Whoever told you that?”

“You did.”

“Surely you have me mistaken for someone else.”

“Impossible. You told me that during our dinner at Jean-Georges. Don’t you remember?”

I-55 guffaws—a hearty laugh that I do not recognize as my own. It emanates from deep in his belly, which he holds with both his hands as he rollicks in his chair. The laugh belongs to a man twice his size and possesses an intangible but real pretension—that only he can appreciate the full hilarity of what you, the ignoramus, have said. It belongs to a pompous man whom I do not recognize as an extension of myself. His snorting laugh goes on for a painfully long time; he even sweats a little bit from the effort and wipes his brow with the linen napkin. He appears done, mercifully, but then resumes laughing, having caught a second wind. This denouement is contrived and painful. He’s forcing it.

Finally he is done.

“I don’t get it,” I say.

“It isn’t your fault.” I-55 dabs at his face one more time. “You’re programmed to think about time sequentially.”

“And this is problematic?”

“I would say limiting.”

“How so?”

“I have no relationship to the man who encouraged you to leave Q, I-60 as you called him then. He is an utter stranger

to me.”

“How can this be? You are practically the same age as he was.”

This is clearly the wrong thing to say. I-55 begins pawing at his face and examining himself in the wall mirror.

“Do you really think I look sixty? I’m only fifty-five, you know. I told you this, didn’t I? Is it my skin? Is it my eyes? It’s my eyes, isn’t it?”

“No,” I say, reassuringly. “You look wonderful. In fact, I was thinking to myself that I hope I look as good as you do when I am your age.”

This is the right thing to say; I-55 decompresses.

“Thank you,” he says.

“All I meant is that you’re both from the future, so I presumed the two of you had something in common.”

I-55 reassumes his bombastic demeanor. “This is the fallacy of post hoc ergo propter hoc.”

“In English.”

“Just because something happens after something else, doesn’t mean it was caused by the other thing. You need to stop thinking sequentially. Do you have a pen?”

I offer him my gel tip.

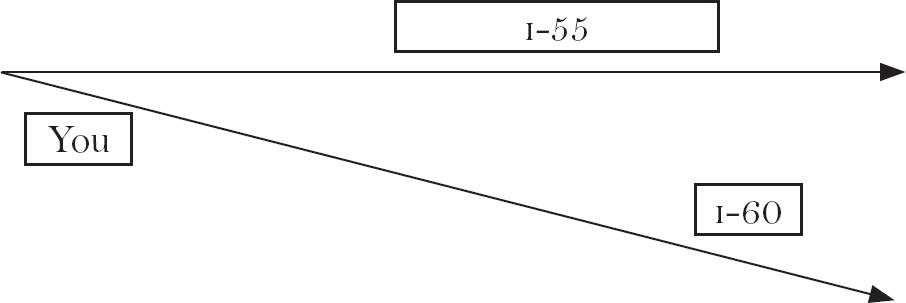

“You see, when I-60 came back to see you, he had already lived a lifetime based on the decision to marry Q and have the child he told you about. After he visited you, he sent you down a different path than you otherwise would have gone down.”

“Okay.”

“Let me try it a different way. I-60, you, and I each had the same experiences up to the point where I-60 came back in time. From there our paths diverged. I-60 lived a life based on his choice to marry Q. You and I have lived a life based on our decision to leave Q. Even though I am older than you, I have not had the same experiences that he had. My life subsequent to the point of his visit has been totally different than his. Look,” he says, and draws on the tablecloth.

“I-60’s life was based on a choice that you did not make. I am you based on the choice that you did make. Do you understand?”

“The truth is, I don’t find visual aids very helpful.” He should know this.

“I am you,” he says. “It’s that simple. Do you understand that?”

“I suppose.”

“That’s why you have to trust me.”

I look at the diagram. It bothers me. “I don’t think it’s appropriate to write on a tablecloth.”

“This is a very fine restaurant.”

“All the more reason not to write on the tablecloth.”

“They can afford it. Besides, they’ll just wash it.”

“Are you sure ink will come out? I don’t think ink will come out.”

“It will. I just saw an infomercial on television for a cleaner that dissolves ink on contact.”

“When did you see that?”

“Just three nights ago, during

The Odd Couple

.”

“Was that before you traveled back in time or after?”

“Before, I think.”

“Are you sure that the cleaner has been invented yet?”

“No. I’m not sure. Now I feel guilty.”

I see from his face that this is genuine, and I feel guilty for making him feel guilty.

“They still show

The Odd Couple

on television?”

“Yes.”

“Does it hold up?”

“Yes.”

“That’s good.”

The waiter returns

with the Kumamoto oysters, the sashimi tacos, the sake, and my Diet Coke. He sets them down on the table, notices the diagram, and frowns. I look to I-55, expecting him to offer an apology, but he remains silent. I have to say something, so I do.

“I’m sorry. We got caught up in the excitement of a conversation and ended up writing on the tablecloth.”

“I can see that.”

“We’re very sorry. We’ll pay for it if it cannot be cleaned.”

“I am not upset about the dirty tablecloth, but that is the clumsiest explanation of the sequential fallacy I have ever seen.”

The waiter leaves. I am agape.

“Does that mean he is from the future?”

“Not necessarily. He could be a theoretical physicist.”

“Working as a waiter?”

“This is New York City,” says I-55. “He probably wants to be an actor.”

I frown.

“It isn’t any less plausible than his being from the future,” he says.

“Does this occur?” I ask again. “Are there people from the future living in the past?”

“You mean the present?”

“My present, their past.”

“A few people. Occasionally people get stuck in the past.”

“Because of a problem with the technology?”

“No. Time travel is safe and reliable.”

“Why then?

“Sometimes they forget to bring money.”

I am about to explore this statement when I-55 bites into a Kumamoto oyster. He appears to savor it.

“When did we start liking these?”

“Just now.”

“You didn’t like them before?”

“I had never tried one before.”

I am incredulous. “You mean you ordered a thirty-dollar appetizer without knowing whether you would like it?”

I-55 smiles. “You know the saying: There’s no time like the present.”

I frown as I-55 bites into a second Kumamoto, which he savors. “These are quite delicious,” he says. “You really should try one.”

Conspicuously, however, he does not offer me a bite.

My patience with myself

is waning.

“What are you here for? What do you want?”

“What I want is another Kumamoto oyster.”

“I am being serious.”

“I am too. This is one of the most delicious things I have ever had. Why haven’t we tried one before?”

“I can’t speak for you, but I never cared for the consistency.”

I-55 is licking his fingers.

“That was a mistake. I have never had anything like this.”

“Why don’t you just order one in your own time period?”

“No, no, no,” he says, shaking his head. “Shellfish aren’t good anymore, and besides they’re very expensive.”

He licks his fingers again. It is repulsive.

“Surely you didn’t come here just for the meal. You must have some business.”

“All right,” he says. “You want to get to it.” I-55 licks his hand one last time, then dips a napkin in his water glass and dabs his finger clean. When he is done, he blows his nose in the napkin. This appears to be his view of the necessary preparation for a serious conversation. I worry that my table manners have degenerated so.

“Okay,” he says. “Let’s get down to business.”

“Okay.”

“Here it is. You must marry Minnie Zuckerman.”

This statement does

not have the same dramatic impact as I-60’s proclamation that I must not marry Q. Q, of course, was the love of my life. Minnie Zuckerman is Hank Snjdon’s secretary. The truth is, I have never given her much thought.

To this point, most of our interactions have consisted of tedious office banter. Minnie sits directly outside Hank’s office, at the front of our department suite. It’s impossible to enter or exit one’s individual office without passing by Minnie. Some of the history professors pay her no mind, but I think a human being should always be acknowledged, so anytime I pass Minnie I make sure to say something. This is a source of stress because I feel compelled to be both civil and witty. Furthermore, I am resolved never to say the same thing twice on any given day.

The first and last interactions of the day are easy. In the morning I say, “Good morning, how are you?” and on the way home in the evening I say, “Have a good night!” The rest of the day can be challenging, though, particularly as I have gotten older and require the bathroom more often. I feel that I can say “What’s up?” once per day, but no more. That quota is generally exhausted by ten o’clock. For the remainder of the morning, we mostly talk about lunch.

The buildup begins early. Around half past nine, I make my first trip to the bathroom and say something like, “Thinking about lunch?” to which Minnie will generally reply, “Starting to.”

An hour or so later, when I make my second trip to the bathroom I will ask something like, “Made a decision yet?” to which Minnie will reply, “A decision has been made.”

Then around twelve thirty, when I generally eat my own lunch, I’ll pass by Minnie’s desk, where she generally eats, and comment on whatever she has ordered. For example, if she has ordered hot and sour soup and an eggroll, which is one of her standards, I will say something like, “Chinese today,” and nod my head approvingly. Minnie generally smiles in return, sometimes inquires about my own lunch, expresses her reciprocal approval, and so it goes.

Up until this moment, I have never given Minnie much consideration, certainly not as the object of romantic or sexual longing. But she is a sweet and gentle girl, and not entirely unattractive. Most days she dresses conservatively, and is a bit on the mousy side to begin with, so it is easy for her to blend in with the gray melamine finish of her workstation. But I recall that at the department Christmas party two years ago she wore a festive red sweater that revealed an enticing décolletage.

“You’re talking about Hank Snjdon’s secretary, right? I just want to make sure.”

“Yes. You seem surprised.”

“It’s just that I really don’t know her very well. She seems nice enough, but I wouldn’t have thought she’d be someone you’d be longing for thirty years later.”

“Twenty-five.”

“Right, sorry. Besides, I wouldn’t have thought she’d be interested in me.”

I-55 looks at me skeptically. “I think you know otherwise,” he says.

Truth be told,

I do have an inkling that Minnie Zuckerman likes me. During the promotional tour for

Time’s Broken Arrow

, I participate in Tom Deer’s famous Out of the Box Reading Series at the World of Fish and Hamsters in Manalapan, New Jersey. I am skeptical about the venue. I don’t really see how guppies and rodents can be co-marketed. I also question the promotional value of the event, but my publicist insists again that all publicity is desirable.