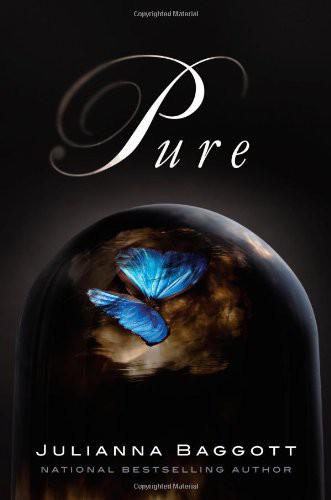

Pure

Authors: Julianna Baggott

Tags: #Fantasy, #Science Fiction, #Young Adult, #Romance, #Paranormal, #Dystopia, #Steampunk, #Apocalyptic

For Phoebe, who made a bird of wire

There was low droning overhead a week or so after the Detonations; time was hard to track. The skies were buckling with dark banks of blackened cloud, the air thick with ash and dust. If it was a plane or an airship of some sort, we never knew because the sky was so clotted. But I might have seen a metal underbelly, some dull shine of a hull dipping down for a moment, then gone. We couldn’t yet see the Dome either. Now bright on the hill, it was only a dusky glow in the distance. It seemed to hover over the earth, orb-like, a lit bobble, unattached.

The droning was some kind of air mission, and we wondered if there would be more bombs. But what would be the point? Everything was gone, obliterated or swept up by the fires; there were dark puddles from black rain. Some drank the water and died from it. Our scars were fresh, our wounds and warpings raw. The survivors hobbled and limped, a procession of death, hoping to find a place that had been spared. We gave up. We were slack. We didn’t take cover. Maybe some were hoping it was a relief effort. Maybe I was too.

Those who could still stagger up from the rubble did. I couldn’t—my right leg gone at the knee, my hand blistered from using a pipe as a cane. You, Pressia, were only seven years old, small for your age, and still pained by your wound raw at the wrist, the burns shining on your face. But you were quick. You climbed up on top of some rubble to get closer to the sound, drawn to it because it was commanding and coming from the sky.

That was when the air took shape, a billowing of shifting, fluttering motion—a sky of singular, bodiless wings.

Slips of paper.

They touched down, settling around you like giant snowflakes, the kind kids used to cut from folded paper and tape to classroom windows, but already grayed by the ashen air and wind.

You picked one up, as did the others who could, until they were all gone. You handed the paper to me and I read it aloud.

We know you are here, our brothers and sisters.

We will, one day, emerge from the Dome to join you in peace.

For now, we watch from afar, benevolently.

Like God,

I whispered,

they’re watching over us like the benevolent eye of God.

I wasn’t alone in this thought. Some were awed. Others raged. We were all still stunned, dazed. Would they ask some of us to enter the gates of the Dome? Would they deny us?

Years would come to pass. They would forget us.

But at first, the slips of paper became precious—a form of currency. That didn’t last. The suffering was too great.

After I read the paper, I folded it up and said, “I’ll hold on to it for you, okay?”

I don’t know if you understood me. You were still distant and mute, your face as blank and wide-eyed as the face of your doll. Instead of nodding your own head, you nodded the doll’s head, part of you forever now. When its eyes blinked, you blinked your own.

It was like this for a long time.

CABINETS

PRESSIA

IS

LYING

IN

THE

CABINET

. This is where she’ll sleep once she turns sixteen in two weeks—the tight press of blackened plywood pinching her shoulders, the muffled air, the stalled motes of ash. She’ll have to be good to survive this—good and quiet and, at night when

OSR

patrols the streets, hidden.

She nudges the door open with her elbow, and there sits her grandfather, settled into his chair next to the alley door. The fan lodged in his throat whirs quietly; the small plastic blades spin one way when he draws in a breath and the opposite way when he breathes out. She’s so used to the fan that she’ll go months without really noticing it, but then there will be a moment, like this one, when she feels disengaged from her life and everything surprises.

“So, do you think you can sleep in there?” he asks. “Do you like it?”

She hates the cabinet, but she doesn’t want to hurt his feelings. “I feel like a comb in a box,” she says. They live in the back storage room of a burned-out barbershop. It’s a small room with a table, two chairs, two old pallets on the floor, one where her grandfather now sleeps and her old one, and a handmade birdcage hung from a hook in the ceiling. They come and go through the storage room’s back door, which leads to an alley. During the Before, this cabinet held barbershop supplies—boxes of black combs, bottles of blue Barbasol, shaving-cream canisters, neatly folded hand towels, white smocks that snapped around the neck. She’s pretty sure that she’ll have dreams of being blue Barbasol trapped in a bottle.

Her grandfather starts coughing; the fan spins wildly. His face flushes to a rubied purple. Pressia climbs out of the cabinet, walks quickly to him, and claps him on the back, pounds his ribs. Because of the cough, people have stopped coming around for his services—he was a mortician during the Before and then became known as the flesh-tailor, applying his skills with the dead to the living. She used to help him keep the wounds clean with alcohol, line up the instruments, sometimes helping hold down a kid who was flailing. Now people think he’s infected.

“Are you all right?” Pressia says.

Slowly, he catches his breath. He nods. “Fine.” He picks up his brick from the floor and rests it on his one stumped leg, just above its seared clot of wires. The brick is his only protection against

OSR

. “This sleeping cabinet is the best we’ve got,” her grandfather says. “Just give it time.”

Pressia knows she should be more appreciative. He built the hiding place a few months ago. The cabinets stretch along the back wall that they share with the barbershop itself. Most of what’s left of the wrecked barbershop is exposed to the sky, a large hunk of its roof blown clean off. Her grandfather stripped the cabinets of drawers and shelves. Along the back wall of the cabinets he’s put in a fake panel that acts like a trapdoor, leading to the barbershop itself, a panel that she can pop off if she needs to escape into the barbershop. And then where will she go? Her grandfather has shown her an old irrigation pipe where she can hide out while

OSR

ransacks the storage room, finding an empty cabinet, and her grandfather tells them that she’s been gone for weeks and probably for good, maybe dead by now. He tries to convince himself that they’ll believe him, that she’ll be able to come back, and

OSR

will leave them alone after this. But of course, they both know this is unlikely.

She’s known a few older kids who ran away—a boy with a missing jaw, then two kids who said they were going to get married far away from here, and a boy named Gorse and his younger sister Fandra, who was a good friend of Pressia’s before they left a few years ago. There’s talk of an underground that gets kids out of the city, past the Meltlands and the Deadlands where there may be other survivors—whole civilizations. Who knows? But these are only whispers, well-intended lies meant to comfort. Those kids disappeared. No one ever saw them again.

“I guess I’ll have time to get used to it, all the time in the world, starting two weeks from today,” she says. Once she turns sixteen, she’ll be confined to the back room and sleep in the cabinet. Her grandfather has made her promise, again and again, that she won’t stray.

It’ll be too dangerous to go out

, he tells her.

My heart won’t take it.

They both know the whispers of what happens to you if you don’t turn yourself in to

OSR

headquarters on your sixteenth birthday. They will take you while you’re asleep in bed. They will take you if you walk alone in the rubble fields. They will take you no matter whom you pay off or how much—not that her grandfather could afford to pay anyone anything.

If you don’t turn yourself in, they will take you. That isn’t just a whisper. That’s the truth. There are whispers that they will take you up to the outlands where you’re untaught to read—if you’ve learned in the first place, like Pressia has. Her grandfather taught her letters and showed her the Message:

We know you are here, our brothers and sisters…

(No one speaks of the Message anymore. Her grandfather has hidden it away somewhere.) There are whispers that they then teach you how to kill by use of live targets. And there are whispers that either you will learn to kill or, if you’re too deformed by the Detonations, you’ll be used as a live target, and that will be the end of you.

What happens to the kids in the Dome when they turn sixteen? Pressia figures that it’s like during the Before—cake and brightly wrapped gifts and fake, candy-stuffed animals strung up and beaten with sticks.

“Can I run to the market? We’re almost out of roots.” Pressia is good at boiling certain kinds of roots; it’s mostly what they eat. And she wants to be out in the air.

Her grandfather looks at her anxiously.

“My name isn’t even on the posted list yet,” she tells him. The official list of those who need to turn themselves in to

OSR

is posted throughout the city—names and birthdates in two tidy columns, information gathered by the

OSR

. The group emerged shortly after the Detonations, when it was Operation Search and Rescue—setting up medical units that failed, making lists of the survivors and the dead, and then forming a small militia to maintain order. But those leaders were overthrown.

OSR

became Operation Sacred Revolution; the new leaders rule by fear and are intent on taking down the Dome one day.

Now the

OSR

mandates that all newborns are registered or parents are punished.

OSR

also does random home raids. People move so frequently that they’ve never had the ability to track homes. There’s no such thing as addresses anymore anyway—what’s left is toppled, gone, street names wiped away. Without her name on that list, it still doesn’t feel quite real to Pressia. She hopes that her name will never appear. Maybe they’ve forgotten she exists, lost a stack of files and hers was in it.

“Plus,” she says. “We need to stock up.” She needs to secure as much food as she can for them before her grandfather takes over the market trips. She’s better at bartering, always has been. She worries what will happen once he’s in charge.

“Okay, fine,” he says. “Kepperness still owes us for my stitch work on his son’s neck.”

“Kepperness,” she repeats. Kepperness paid up a while ago. Her grandfather sometimes remembers only the things he wants to. She walks to the ledge under the splintered window where there’s a row of small creatures she’s made from pieces of metal, old coins, buttons, hinges, gears she collects—little windup toys—chicks that hop, caterpillars that scoot, a turtle with a small snapping beak. Her favorite is the butterfly. She’s made half a dozen of them alone. Their skeletal systems are built from the teeth of old black barber combs and wings made from bits of the white smocks. The butterflies flap when they get wound up, but she’s never been able to get them to fly.

She picks up one of the butterflies, winds it. Its wings shudder, kicking up a few bits of ash that swirl. Swirling ash—it’s not all bad. In fact, it can be beautiful, the lit swirl. She doesn’t want to see beauty in it, but she does. She finds little moments of beauty everywhere—even in ugliness. The heaviness of the clouds draping across the sky, sometimes edged dark blue. There’s still dew that rises from the ground and beads up on pieces of blackened glass.

Her grandfather is looking out the alley door, so she slips the butterfly in the sack. She’s been using these to barter with since people have stopped coming to him for stitching.

“You know, we’re lucky to have this place—and now an escape route,” her grandfather says. “We were lucky from the start. Lucky that I got to the airport early to pick you and your mother up at Baggage Claim. What if I hadn’t heard there was traffic? What if I hadn’t headed out early? And your mother,

she was so beautiful

,” he says, “

so young.

”

“I know, I know,” Pressia says, trying not to sound impatient, but it’s a well-worn speech. He’s talking about the day of the Detonations, just over nine years ago when she was six years old. Her father was out of town on business. An accountant with light hair, he was pigeon-toed, her grandfather liked to tell her, but a good quarterback. Football—it was a tidy sport played on a grassy field, with buckled helmets and officials who blew whistles and threw colored handkerchiefs. “But what does it mean, anyway, that my father was a pigeon-toed quarterback if I don’t remember him? What is a beautiful mother worth if you can’t see her face in your head?”