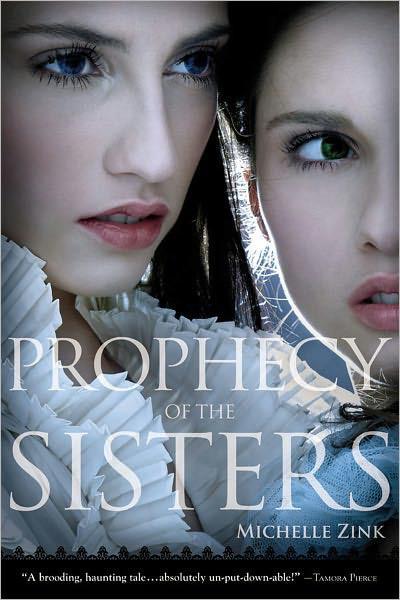

Prophecy of the Sisters

Read Prophecy of the Sisters Online

Authors: Michelle Zink

Copyright © 2009 by Michelle Zink

Hand-lettering and interior ornamentation by Leah Palmer Preiss

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written

permission of the publisher.

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

Little, Brown and Company is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Little, Brown name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

First eBook Edition: August 2009

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental

and not intended by the author.

ISBN: 978-0-316-05334-1

Contents

To my mother, Claudia Baker.

To my mother, Claudia Baker.

For betting on me.

Perhaps because it seems so appropriate, I don’t notice the rain. It falls in sheets, a blanket of silvery thread rushing

to the hard almost-winter ground. Still, I stand without moving at the side of the coffin.

I am on Alice’s right. I am always on Alice’s right, and I often wonder if it was that way even in our mother’s womb, before

we were pushed screaming into the world one right after the other. My brother, Henry, sits near Edmund, our driver, and Aunt

Virginia, for sit is all Henry can do without the use of his legs. It was only with some effort that Henry and his chair were

carried to the graveyard on the hill so that he could see our father laid to rest.

Aunt Virginia leans in to speak to us over the drumming rain. “Children, we must be going.”

The reverend has long since left. I cannot say how long we have been standing at the mound of dirt where my father’s body

lay, for I have been under the shelter of James’s umbrella, a quiet world of protection providing the smallest of buffers

between me and the truth.

Alice motions for us to leave. “Come, Lia, Henry. We’ll return when the sun is shining and lay fresh flowers on Father’s grave.”

I was born first, though only by minutes, but it has always been clear that Alice is in charge.

Aunt Virginia nods to Edmund. He gathers Henry into his arms, turning to begin the walk back to the house. Henry’s gaze meets

mine over Edmund’s shoulder. Henry is only ten, though far wiser than most boys of his age. I see the loss of Father in the

dark circles under my brother’s eyes. A stab of pain finds its way through my numbness, settling somewhere over my heart.

Alice may be in charge, but I am the one who has always felt responsible for Henry.

My feet will not move, will not take me away from my father, cold and dead in the ground. Alice looks back. Her eyes find

mine through the rain.

“I’ll be along in a moment.” I have to shout to be heard, and she nods slowly, turning and continuing along the path toward

Birchwood Manor.

James takes my gloved hand in his, and I feel a wave of relief as his strong fingers close over mine. He moves closer to be

heard over the rain.

“I’ll stay with you as long as you want, Lia.”

I can only nod, watching the rain leak tears down Father’s gravestone as I read the words etched into the granite.

Thomas Edward Milthorpe

Beloved Father

June 23, 1846–November 1, 1890

There are no flowers. Despite my father’s wealth, it is difficult to find flowers so near to winter in our town in northern

New York, and none of us have had the energy or will to send for them in time for the modest service. I am ashamed, suddenly,

at this lack of forethought, and I glance around the family cemetery, looking for something, anything, that I might leave.

But there is nothing. Only a few small stones lying in the rain that pools on the dirt and grass. I bend down, reaching for

a few of the dirt-covered stones, holding my palm open to the rain until the rocks are washed clean.

I am not surprised that James knows what I mean to do, though I don’t say it aloud. We have shared a lifetime of friendship

and, recently, something much, much more. He moves forward with the umbrella, offering me shelter as I step toward the grave

and open my hand, dropping the rocks along the base of Father’s headstone.

My sleeve pulls with the motion, revealing a sliver of the strange mark, the peculiar, jagged circle that bloomed on my wrist

in the hours after Father’s death. I steal a glance at James to see if he has noticed. He hasn’t, and I pull my arm further

inside my sleeve, lining the rocks up in a careful row. I push the mark from my mind. There is no room there for both grief

and worry. And grief will not wait.

I stand back, looking at the stones. They are not as pretty or bright as the flowers I will bring in the spring, but they

are all I have to give. I reach for James’s arm and turn to leave, relying on him to guide me home.

It is not the warmth of the parlor’s fire that keeps me downstairs long after the rest of the household retires. My room has

a firebox, as do most of the rooms at Birchwood Manor. No, I sit in the darkened parlor, lit only by the glow of the dying

fire, because I do not have the courage to make my way upstairs.

Though Father has been dead for three days, I have kept myself well occupied. It has been necessary to console Henry, and

though Aunt Virginia would have made the arrangements for Father’s burial, it seemed only right that I should help take matters

in hand. This is what I have been telling myself. But now, in the empty parlor with only the ticking mantel clock for company,

I realize that I have been avoiding this moment when I shall have to make my way up the stairs and past Father’s empty chambers.

This moment when I shall have to admit he is really gone.

I rise quickly, before I lose my nerve, focusing on putting one slippered foot in front of the other as I make my way up the

winding staircase and down the hall of the East Wing. As I pass Alice’s room, and then Henry’s, my eyes are drawn to the door

at the end of the hall. The room that was once my mother’s private chamber.

The Dark Room.

As little girls, Alice and I spoke of the room in whispers, though I cannot say how we came to call it the Dark Room. Perhaps

it is because in the tall-ceilinged rooms where fires blaze nonstop nine months out of the year, it is only the un-inhabited

rooms that are completely dark. Yet even when my mother was alive, the room seemed dark, for it was in this room that she

retreated in the months before her death. It was in this room that she seemed to drift further and further away from us.

I continue to my room, where I undress and pull on a nightgown. I am sitting on the bed, brushing my hair to a shine, when

a knock stops me midstroke.

“Yes?”

Alice’s voice finds me from the other side of the door. “It’s me. May I come in?”

“Of course.”

The door creaks open, and with it comes a burst of cooler air from the unheated hallway. Alice closes it quickly, crossing

to the bed and sitting next to me as she did when we were children. Our nightdresses, like us, are nearly identical. Nearly

but not quite. Alice’s are made with fine silk at her request while I prefer comfort over fashion and wear flannel in every

season but summer.

She reaches out a hand for the brush. “Let me.”

I hand her the brush, trying not to show my surprise as I turn away to give her access to the back of my head. We are not

the kind of sisters who engage in nightly hair brushing or confided secrets.

She moves the brush in long strokes, starting at the crown of my head and traveling all the way down to the ends. Watching

our reflection in the looking glass atop the bureau, it is hard to believe anyone can tell us apart. From this distance and

in the glow of the firelight, we look exactly the same. Our hair shimmers the same chestnut in the dim light. Our cheekbones

angle at the same slant. I know, though, that it is the subtle differences that are unmistakable to those who know us at all.

It is the slight fullness in my face that stands in contrast to the sharper contours of my sister’s and the somber introspection

in my eyes that opposes the sly gleam in her own. It is Alice who shimmers like a jewel under the light, while I brood, think,

and wonder.

The fire crackles in the firebox, and I close my eyes, allowing my shoulders to loosen as I fall into the soothing rhythm

of the brush in my hair, Alice’s hand smoothing the top of my head as she goes.

“Do you remember her?”

My eyelids flutter open. It is an uncommon question, and for a moment, I’m unsure how to answer. We were only girls of six

when our mother died in an inexplicable fall from the cliff near the lake. Henry had been born just a few months before. The

doctors had already made it clear that my father’s long-desired son would never have the use of his legs. Aunt Virginia always

said that Mother was never the same after Henry’s birth, and the questions surrounding her death still linger. We don’t speak

of it or the inquiry that followed.