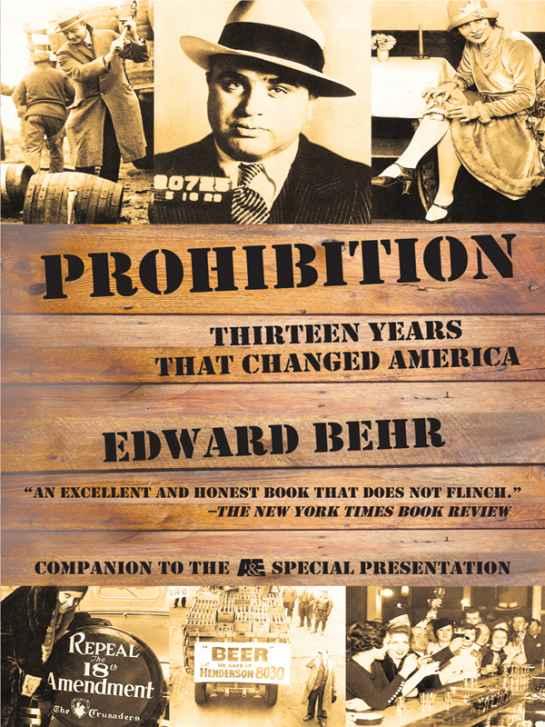

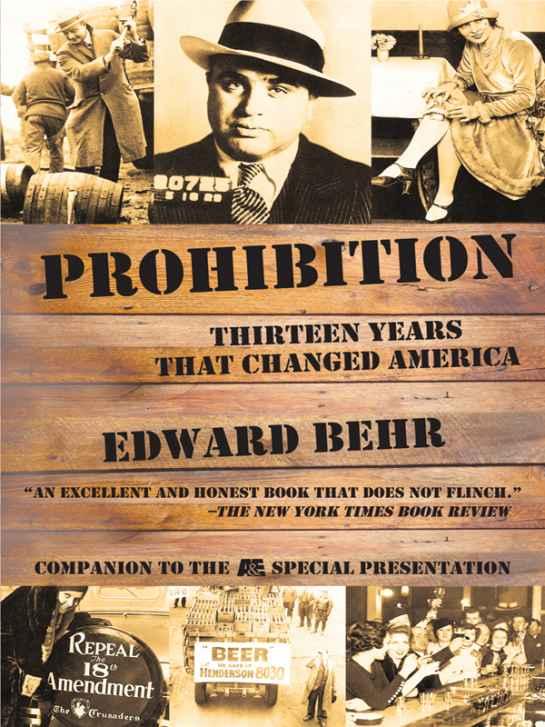

Prohibition: Thirteen Years That Changed America

Read Prohibition: Thirteen Years That Changed America Online

Authors: Edward Behr

PROHIBITION

Also by Edward Behr

T

HE

A

LGERIAN

P

ROBLEM

T

HE

T

HIRTY

-S

IXTH

W

AY

(with Sidney Liu)

“A

NYONE

H

ERE

B

EEN

R

APED AND

S

PEAKS

E

NGLISH

?”

G

ETTING

E

VEN

T

HE

L

AST

E

MPEROR

H

IROHITO

: B

EHIND THE

M

YTH

T

HE

C

OMPLETE

B

OOK OF

L

ES

M

ISÉRABLES

K

ISS THE

H

AND

Y

OU

C

ANNOT

B

ITE

: THE RISE AND FALL OF THE CEAUSESCUS

T

HE

S

TORY OF

M

ISS

S

AIGON

(with Mark Steyn)

PROHIBITIONT

HE

G

OOD

F

RENCHMAN

(T

HE

L

IFE AND

T

IMES OF

M

AURICE

C

HEVALIER

)

THIRTEEN YEARS THAT CHANGED AMERICA

EDWARD BEHR

ARCADE PUBLISHING • NEW YORK

Copyright © 1996, 2011 by Edward Behr

All Rights Reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Arcade Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Arcade Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or

[email protected]

.

Arcade Publishing® is a registered trademark of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at

www.arcadepub.com

.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Behr, Edward, 1926-2007.

Prohibition : thirteen years that changed America / Edward Behr.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61145-009-5 (alk. paper)

1. Prohibition—United States—History. 2. Drinking of alcoholic beverages—United States—History. 3. Alcoholism—United States—History. I. Title.

HV5089.B424 2011

363.4’1097309042--dc22

2011004232

Printed in the United States of America

P

hilip Guedalla once said that while history repeats itself, historians repeat each other—and all writers on Prohibition owe a huge debt to Herbert Asbury, whose

Great Illusion

remains the best record of its historical and evangelical origins. Another essential source book is

Wayne Wheeler: Dry Boss

, by Justin Stewart, Wheeler’s former private secretary. I have also drawn heavily on the insider accounts of Prohibition by Roy Haynes, one of the first Prohibition Bureau commissioners, and Mabel Walker Willebrandt, who was deputy attorney general in charge of Prohibition law enforcement from 1921 to 1929.

I also want to thank the New York, St. Louis, Cincinnati, and East Hampton public libraries for their helpful cooperation, and the Library of Congress for its material on the Senate Investigative Committee on Attorney General Daugherty in 1924. I am especially beholden to a number of Cincinnati residents and experts: Jim Bruckmann, who reminisced about the pre-Prohibition fortunes of his family brewery; Jack Doll, gifted amateur photographer and organizer of a remarkable photo exhibition on George Remus; Geoffrey Giuglierino; Dr. Don H. Todzmann of the University of Cincinnati— and coundess others, on Long Island and the East Coast, who were kind enough to share with me the family tales and reminiscences of not so long ago.

I would also like to thank my agent, Jean-Francois Samuelson, for his unfailing support, and my old friend and colleague Anthony Geffen for his constant encouragement. Thanks to him, what began as a vague telephone conversation ended up not only as a book but as an international, three-part television series.

E

arly one fine autumn morning — October 6, 1927 — a stocky, middle-aged man named George Remus ordered George Klug, his driver, to overtake a taxi in Cincinnati’s Eden Park. He had been tailing it ever since it had left the Alms Hotel with its two women passengers. After driving alongside, and motioning it to stop — it failed to do so — Remus got the driver to swerve suddenly, forcing the taxi off the road.

The cabdriver swore and hit the brakes, barely avoiding a collision, and the two women were shaken nearly off their seats. The older one, Imogene, was Remus’s wife, and she was on her way to her divorce court hearing. By today’s standards, she was distinctly on the stocky side, but her opulent figure, ample curves, and huge, gray-green eyes were typical beauty canons of the time, and her clothes — a black silk dress, patent leather black shoes, and black cloche hat from Paris — identified her as a woman of means. The younger woman, her daughter Ruth by an earlier marriage, was a slightly dumpy twenty-year-old.

As Ruth would later tell the court, at Remus’s trial, Imogene gasped, “There’s Remus,” when she first spotted the overtaking car. Imogene got out of the stationary cab as Remus emerged from

his

car, a gun in his right hand (the defense later challenged this evidence, for Remus was left-handed). Ruth recounted: “He hit her on the head with his fist.” Imogene said, “Oh, Daddy, you know I love you, you know I love you!” Remus turned to Ruth. “She can’t get away with

that,”

he snarled.

Imogene shrieked, “For God’s sake, don’t do it!” as Ruth, also spotting the gun, shouted, “Daddy, what are you going to do?” Then Imogene screamed, “Steve [the taxi driver], for God’s sake, come over and help me!” But the driver stayed put. He heard George Remus shout, “Damn you, you dirty so-and-so bitch,

damn

you, I’ll

get

you.”

Imogene then rushed back into the cab, pursued by Remus. That was when he shot her, once in the stomach. She had the strength to get out of the other side of the car, running, her hands above her head, with Remus still in pursuit. She then got into another car, which had come to a halt behind the stalled taxicab, and collapsed.