Prisoner of the Vatican (30 page)

Read Prisoner of the Vatican Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

The intransigents' triumph was evident in

Civiltà Cattolica.

In January 1881, Father Gaetano Zocchi put it this way: "There is the Rome of the Popes and the Rome of the Freemasons. There is the Rome that prays and the one that swears, Rome of the martyrs and Rome of the tyrants; blessed Rome and cursed Rome. There is the Rome made of granite and the Rome made of papier-mà ché, eternal Rome and the Rome that, born yesterday, is unsure it will see tomorrow. There is the Rome of Christ and the Rome of the Anti-Christ." Was there any chance of reconciliation between these two Romes? he asked. Only people lost in a fantasy world could think so. "And no conciliation between them being possible, which of the two will emerge as the winner of the battle?" the Jesuit journal asked. "Which will live on even more glorious and more beautiful and which will be smashed to pieces?" The question, of course, was rhetorical, the winner divinely ordained. And there could be no doubt of Leo XIII's resolve, Zocchi continued. "He is as firm as can be in continuing the glorious struggle sustained by his saintly Predecessor against those who call themselves

Italy,

but who are instead revolution, Freemasons, satanism."

38

A

FEW DAYS BEFORE

he was elected pope, Gioacchino Pecci, in his role as chamberlain, called in the dead pontiff's relatives for a reading of his last testament, eleven sheets of paper written in Pius's hand, bound by a silk ribbon. To the surprise of some who heard it, Pius asked that he be entombed, not in one of Rome's great churches, but in the modest basilica of San Lorenzo, outside the city walls. He specified the exact location in the church that he had chosen and instructed that no more than four hundred scudi be spent to build the shrine. The inscription was likewise to be modest: "Here lie the bones and mortal remains of Pius IX," along with the dates of his papacy and the date of his death. The only symbol to be placed over the inscription was a death's head. In the meantime, as was the custom, the pope's body was placed in St. Peter's.

1

Just what it was that led Leo XIII to decide to hold the funeral procession three years after Pius's death remains unclear. It was customary to wait until the death of a pope's successor for such a reburial ceremony, but the three cardinals Pius had named as his executors were, for some reason, impatient. Yet in their haste to have his body taken to San Lorenzo, they recognized the risks they were running. Such a move would require a procession through the entire city. Given what Pius IX, the last pope-king, represented to the people of Rome, the prospect of provoking violent anticlerical demonstrations surely occurred to them. Nor was it clear initially that the Italian authorities would allow such a rite, although the law of guarantees assured the pope the same honors as those given the king. Since 1876 the government had forbidden all outdoor religious processions in Rome, arguing that they threatened the public order. And, given the hostile climate, the Church leaders themselves had not been eager to face the taunts and worse of the anticlericals by marching through the city streets. It was for this reason that ever since 1870, even the annual Corpus Domini procession, normally one of the most impressive public rites in the Holy City, had been abandoned.

2

Pius IX's executors could hardly have been better placed in the Church: Raffaele Monaco la Valletta, cardinal vicar of Rome, Giovanni Simeoni, Pius's secretary of state, and Teodolfo Mertel, who, along with Antonelli, was one of the last men to serve as a cardinal without ever having been ordained a priest. In the recriminations and finger-pointing that followed the funeral events, some charged the three cardinals with having pushed a reluctant pope into approving the procession. Whatever the case, in discussing the plans with the pope and his secretary of state, the executors concluded that it would be too risky to hold the procession in daylight. It also appears that the pope thought it best to keep the rite as secret as possible to minimize the risks of confrontation or violence on the city's streets.

As cardinals, the executors could not enter into direct negotiations with the Italian authorities, so they deputized a layman, Virginio Vespignani, a Roman architect from a noble family, as their intermediary. On June 23, 1881, he wrote to Rome's prefect on their behalf asking for authorization to transport Pius IX's body from St. Peter's to San Lorenzo on a night between July 1 and July 16. On June 28, the prefect responded that as soon as they informed him of the specific night, he would make the arrangements. On July 5, the architect again wrote to the prefect, setting the date for midnight on Tuesday, July 12, and describing the route to be taken. According to the architect, the procession would be modest: "The cortège will consist of a wagon with the coffin covered with a funeral pall, drawn by four horses, and two or three carriages following. There will not be any external sign. All will proceed in a totally private fashion." With the date and route fixed and the pledge that it would be only a small, private ceremony, the prefect gave his approval. He would see that the necessary security was provided.

3

Just what assurances the Vatican gave the Italian authorities remain one of the points in the dispute that followed. Two days after the violent events on the night of the procession, an emergency inquiry was conducted at the behest of Depretis, the prime minister, who also served as minister of the interior. As part of the inquest, Signor Baccoâwho as

questore

served as the head of the police services for the prefect of Romeâdescribed how he was first informed of the plans. "On the 9th, at just about the same time, I was called in both to see the general director of public security for the minister of the interior and to the prefect's office. I went first to the ministry, where Commissioner Bolis [head of the police in Rome] told me that the transport of Pope Pius IX's body was going to take place in an absolutely private manner, and he gave me responsibility for taking some purely precautionary measures, as there was nothing unusual to be worried about."

Bacco recalled voicing some concern: "I replied to Commissioner Bolis that it was a mistake to think that the transport would take place quietly, without a crowd of followers, since there was already great ferment among Catholics, for the news of the transport had reawakened all the devotion and sympathy that these people felt for the Pontiff." And in this recollection, recorded in the wake of the disaster and with the knowledge that heads would have to roll, Bacco made sure to cast the blame elsewhere: "Commissioner Bolis in the end did not believe that at midnight many people would gather to follow a long route such as that from St. Peter's to San Lorenzo."

By the following day, signs of trouble appeared. The prime minister was getting reports that, despite the Vatican's assurances, the "private" procession was going to become a mass demonstration of loyalty to the last of the pope-kings. Rattled, the secretary-general of the minister of the interior called in Bacco. "I wouldn't like to see the procession assumeâdue to the clericals' involvementâthe nature of a political demonstration," he said. "True, there are not a great many of them, but in any case it would make a bad impression to hear it said that Rome is still today devoted to the pope." Bacco was told to ensure that all went quietly.

But Bacco was uneasy. Were he to try to prevent people from taking part in the procession, the Church would certainly complain that the government was keeping the faithful from a funeral rite. "I also said," the

questore

recalled, "that there should be no illusions about the number of Romans who remained loyal to the Pope, for there are a great many of them."

He was then escorted to the prime minister's office. Described by Bacco as both listless and brusque, Depretis asked him whether he thought the funeral cortege could proceed in such a way that it would avoid attracting attention, "since it would not be good if there were much hubbub and it was given much importance."

The following day, Monday, the eleventh, Bacco received a series of disturbing reports from his informants. A meeting had been held at one of Rome's radical clubs, with two parliamentary deputies present. The radicals were convinced that if the funeral cortege proceeded without protest, it would give the impression that the government was in league with the Vatican. Worse still, the world would conclude that the Romans were devoted to the pope. Bacco was also told that news of the supposedly private cortege had spread among Rome's loyal Catholics, who were planning to turn out in great number.

That day Bacco received two unexpected visitors, Cesare Crispolti and Alessandro Datti, two of Rome's most prominent lay Catholics. The fullest account we have of their visit comes from a report they made to the Vatican secretary of state a few days later, at the height of the procession polemics. On Sunday evening, they recalled, while talking with friends, they had decided that it would be best to notify the authorities that what they had initially thought was going to be a small, private funeral cortege was clearly turning into something very different. After receiving approval from (unspecified) Vatican authorities for their plan, Crispolti and Datti were deputized to speak to the police authorities. At 6

P.M

. the next day they were ushered into Bacco's office.

They had come, they said, in a private capacityâalthough it is hard to believe they would have engaged in such a mission without the Vatican's encouragementâto be sure that the authorities allowed all those Romans who so desired to join the funeral procession. Bacco expressed his consternation that the supposed secret had become so publicly known, pointing out that even the morning's newspaper had carried a story about it. Would the participants be carrying torches and singing songs? he asked. Yes, the men replied, they would be carrying torches, singing songs, and reciting the rosary. "He then observed," Crispolti and Datti recalled, "that police regulations in fact prohibited such a funeral procession because they specified that after 11, the city should remain quiet. Nonetheless, persuaded that all would unfold in a satisfactory manner, he left us complete freedom to do what we had told him was planned."

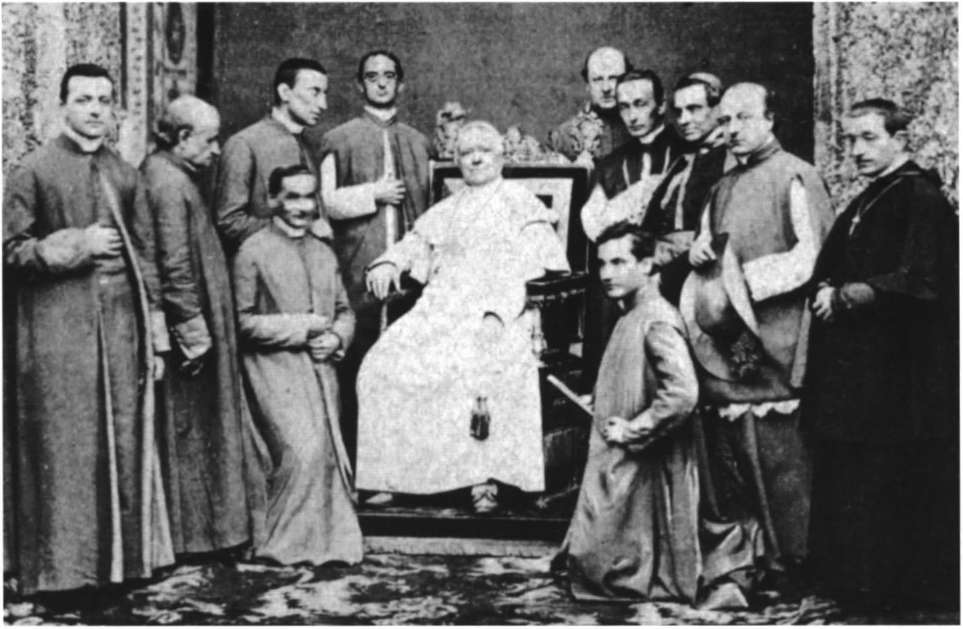

Pius IX with his court in the 1850s.

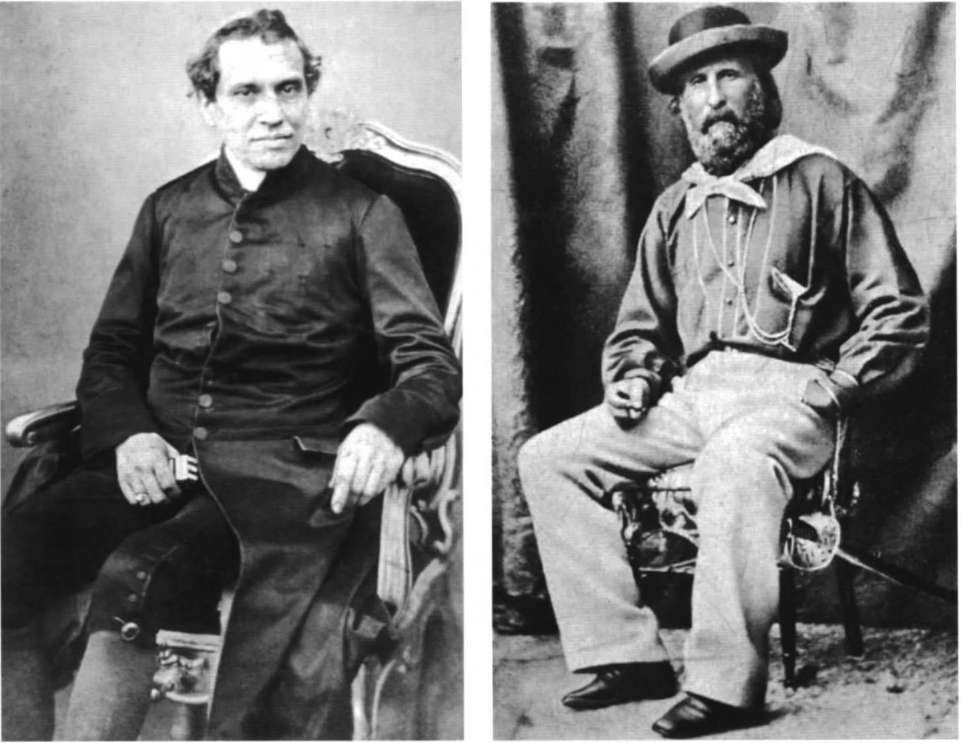

Cardinal Antonelli, secretary of state, in the 1850s.

Giuseppe Garibaldi, in a red shirt, at the time of his expedition to Sicily, 1860.

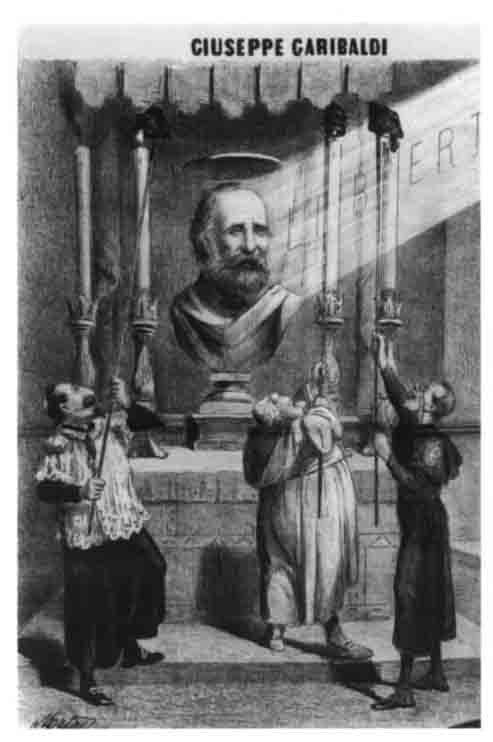

This satirical image from 1863 shows Pope Pius IX and Napoleon III unsuccessfully trying to prevent the heavenly lightâlabeled "Freedom"âfrom shining on Garibaldi, the object of popular adulation.