Prisoner of the Vatican (10 page)

Read Prisoner of the Vatican Online

Authors: David I. Kertzer

from impregnable against modern artillery, the pope's soldiers could not possibly prevail. To order them to fight was to consign many of them to a death that would, in a military sense, have little purpose. Yet he was loath to allow the Italians to take Rome without a fight, believing that to do so might be interpreted as showing that he had given his consent. On September 7, Pius called in his three generals and said that while they should mount a clear resistance to the attack, its aim should be above all to show that the city was being taken by force. Once they had made this clear, they should surrender.

8

The American consul in Rome, D. Maitland Armstrong, offers an enticing glimpse of what Roman life was like in the days preceding the final battle. As it happened, the consul had returned to Rome in mid-September using the same gate that the Italian troops would use to enter the city a few days later. He described the earthen barricades and deep trench outside Porta Pia and the piles of sandbags reinforcing the inner side. In these final days of papal Rome, Armstrong observed, the city "was in a state of quiet expectancy, almost, it seemed of apathy, the streets were comparatively deserted, most of the shops closed, all telegraphic and postal communication cut off, from the 12th until the 23d of September the mails were not received. On the walls were posted proclamations declaring the city in a state of siege, forbidding all people to enter or leave the city, or to assemble in any considerable numbers in the streets."

9

He described a population having little enthusiasm for continued papal rule, noting that despite the desperate attempts of the authorities to attract volunteers to defend the Holy City, only two hundred in all of Rome were willing to enlist, and "with the exception of these and the few Romans already in its service not one of the people raised a hand for the defence of the Papacy." Unsavory men who had previously served the papal authorities as spies were now given uniforms and patrolled the streets, fueling popular resentment.

At 5

A.M.

on September 20 the attack began, moving along an arc that ran across a third of the city walls, with cannons booming out forty shots each minute. Armstrong gave this eyewitness account:

The old walls generally proved utterly useless against heavy artillery, in four or five hours they were in some places completely swept away, a clear breach was made near the Porta Pia fifty feet wide, and the Italian soldiers in overwhelming force flowed through it and literally filled the city, simultaneously the Porta San Giovanni was carried by assault. A white flag was hoisted over from the dome of St. Peter's. After the cannonading ceased the papal troops made but a feeble resistance, and they who a moment before ruled Rome with a rod of iron, were nearly all prisoners, or had taken refuge in the Castle of St. Angelo, or St. Peter's square.

The Italian forces avoided unnecessary damage or bloodshed, according to Armstrong, as they aimed their fire solely against the outer walls and not into the city: the only noncombatant deaths came as the result of stray shots. Indeed, a bullet had gone through the American consulate's window.

The disinclination of the papal forces to fight more fiercely, in the American consul's view, was reinforced by their realization that the people of Rome welcomed the Italians as their liberators, as "no private citizens made the least effort or demonstration in favor of the Papal Government." In all, Armstrong reported:

it was an easy victory for the Italians, and the loss, in killed and wounded, on both sides, was not great, they were in over-whelming force, with very heavy artillery and they knew that the mass of Romans were their friends; the Zouaves [the papal troops], on the other hand, although they never could have imagined how much they were detested, must have, at heart, feared the people, and could not fight their best; they were a fine looking body of men, many of them, even the common soldiers, of superior education and refinement, some of them undoubtedly served the Pope from religious feeling, many for the sake of the romance and adventure of the thing, very few for pay, as it was ridiculously small.

10

The consul's account was mistaken on at least one count. While the troops in the major line of assaultâunder Cadorna's commandâlimited their fire to the destruction of the walls, the troops on the other side of the city, charged with creating a distraction, did not. Under General Nino Bixio, they lobbed cannon shots perilously close to St. Peter's itself.

Bixio was a colorful, swashbuckling, but also rather troubled figure. Born in Genoa in 1821, he had been the uncontrollable son of a wealthy father, his mother having died when he was young. Not knowing what to do with the willful child, his father sent him off into the merchant marine at the age of thirteen, and while still a youth he had suffered a shipwreck and imprisonment in the West Indies. In 1847, already a devout republican, Bixio met Mazzini and joined the revolts of 1848. Fighting alongside Garibaldi, he was wounded defending the Roman Republic in 1849. Ten years later, as Garibaldi's right-hand man, he accompanied the hero through Tuscany and Romagna before being given command of one of the two ships that carried Garibaldi's "thousand" volunteers to Sicily in 1860. He was far from loved by his men, who feared his violent temper.

Cadorna had never liked Bixio, whom he saw as more suited for the role of leader of the revolutionary rabble than a proper military officer, but Bixio had been the beneficiary of the policy that brought Garibaldi's irregulars into the official Italian army a decade earlier. Addressing parliament in the 1860s, the flamboyant Bixio had proposed his own solution to the Roman question: the matter was simple, he said. Just throw the pope and all of his cardinals into the Tiber.

11

By 6

A.M.,

only an hour after the first sounds of battle were heard, members of the diplomatic corps began to arrive at the Vatican to be with the pope on what they knew would be a historic day. Wearing their finest uniforms and riding in their best carriages, eleven foreign envoys made their way in, including the ambassadors of Prussia, Austria, and France. At seven-thirty the pope, as was his habit, entered his private chapel, along with Antonelli and other members of his entourage. There the diplomats had the strange experience of hearing the pope say mass to the sounds of the cannons.

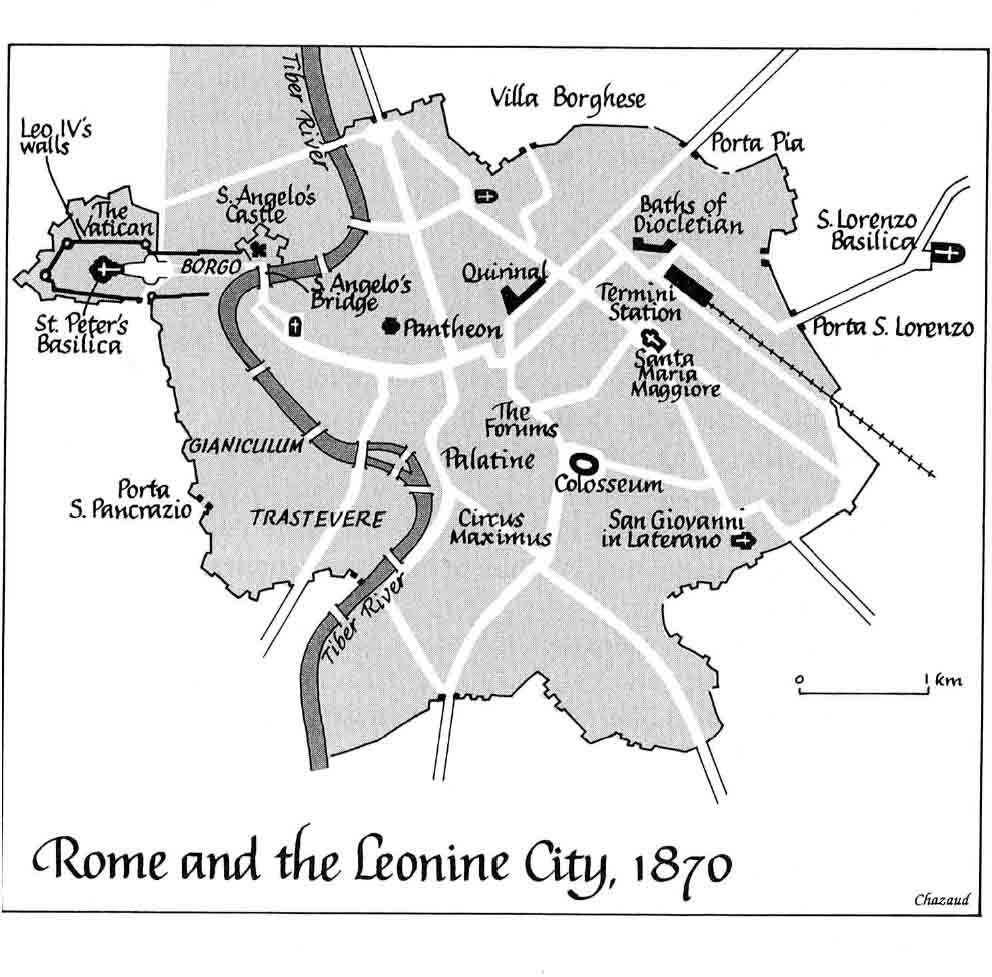

The pope then assembled the diplomats in his library, where he launched into a long monologue. Those who reported on the meeting observed that the pope seemed oddly impervious to what was going on outside. After thanking them for their presence on this sad occasion, he appeared to lose himself in memories of years past, dwelling on the pleasant times he had had as a young man, in 1823, when he sailed to South America as a member of the papal diplomatic corps. In the midst of these reveries, he was interrupted by the arrival of Count Carpegna, Kanzler's chief of staff, who brought news of the opening of a breach in the walls at Porta Pia. The pope hurried out, with Antonelli at his side, as they prepared Kanzler's final orders. It took little time for the terms of the surrender to be drafted by General Cadorna and signed by Kanzler. All of Rome, excluding the Leonine city, was nowceded to the army of His Majesty the king of Italy. The defeated papal troops were escorted back to St. Peter's Square, protected from the jeering Romans by troops bearing the Italian tricolored flag.

12

The dream of a unified Italy had come to pass. Uncensored newspapers could now appear. One of the first, on September 23, captured the delirious mood:

After fifteen centuries of darkness, of mourning, of misery and pain, Rome, once the queen of all the world, has again become the metropolis of a great State. Today, for us Romans, is a day of indescribable joy. Today in Rome freedom of thought is no longer a crime, and free speech can be heard within its walls without fear of the Inquisition, of burnings at the stake, of the gallows. The light of civil liberty that, arising in France in 1789, has brightened all Europe now shines as well on the eternal city. For Rome it is only today that the Middle Ages are over.

13

The mood of the pope's defenders was glum. Yet they were not without their own hopes for the future, drawing comfort from the knowledge that Rome had been overrun by invaders many times before. In each case God had made sure that the Holy City was restored to its divinely ordained owners, its enemiesâHis enemiesâbrought low.

14

T

WO MONTHS AFTER

the Holy City was taken, an Italian government envoy went to see Bishop Giovanni Simeoni, secretary of the Vatican's Congregation for the Propagation of the Faith, the body in charge of the Church's missions overseas. He wanted to sound the bishop out on ways that the government might cooperate with the Catholic missions abroad to their mutual benefit, but the bishop would hear none of it. The Holy See could not have any dealings with a government that had usurped the pope of his rightful earthly kingdom, said the bishop, and, in any case, he believed, the days of the new regime were numbered. "It is for us just a matter of time," he predicted. "When it will be, I don't know. It might be postponed a bit, but someday I will have the pleasure of writing you that the Restoration has come." Like others around the pope, Simeoni made no distinction between the restoration of the pope's rule in Rome itself and the restoration of the entire Papal States, for they were one and the same. Nor was this illusion shared only by prelates in Rome. In this sense, the letter that Archbishop Martin Spalding of Baltimore sent in early October 1870 was typical. "Our most beloved Father should be consoled," he wrote, for "such an abnormal state of affairs certainly cannot last very long. Divine providence will soon bring the needed remedy. I couldn't be more convinced of it."

1

The leaders of the Italian government, meanwhile, had other ideas. In his early September letter to the pope, the king had specifically promised him full sovereignty over the right bank of the Tiber, intend ing that Rome would be forever divided between its secular left bank, over which he would preside, and the sacred domain of the Church on the right. This view is reflected in the September 23 comments of one of Italy's most prominent statesmen, Marco Minghetti, the former prime minister who was then serving as Italian ambassador to Vienna. "Italian troops will not enter the Leonine city," he wrote to Lord Acton that day.

2

What he did not realize was that the soldiers were already there.

On September 21, as General Cadorna stood at Porta San Pancrazio, south of the Leonine city, reviewing the foreign pontifical troops heading out of the country, he was surprised by the arrival of Count Harry von Arnim, the Prussian ambassador to the Holy See, who urgently sought his attention. Scuffling had broken out in the Leonine city between the papal gendarmes and the

popolani,

the lower classes, Arnim told him. The pope was upset, and those around him feared for his safety. Pius, according to Arnim, asked that Italian troops be sent in to preserve order.

Cadorna had told his troops not to enter the Leonine city, which he had defined very broadly to include not only the area within the old walls erected in the ninth century by Leo IVâcontaining the Vatican, the residential area between the Vatican and the Tiber (called the Borgo), and the Sant'Angelo Castleâbut also the stretch of largely unoccupied land to the south going up the Gianiculum hill to the Porta San Pancrazio, where he now stood. Cadorna was not pleased by the pope's request. Certainly, he argued, Pius had sufficient forces left to maintain order, for he had Noble Guards, Palatine guards, Swiss guards, and gendarmesâonly the papal army itself had been disbanded. But if, Cadorna told the Prussian ambassador, the pope still needed the Italian forces, he would have to put his request in writing and either sign it himself or have Antonelli or Kanzler do so.

While Arnim's carriage rattled over the cobblestone streets back to the Vatican, Cadorna sent orders for two of his battalions to move into position at the Sant'Angelo bridge, taking care to remain on the left bank. Arnim soon returned with a letter signed by Kanzler. "His Holiness has asked me to inform you," the general wrote, "that he wants you to take energetic and effective measures for the protection of the Vatican, for with all of his troops now dissolved, he lacks the means to prevent those who would disturb the peaceâboth immigrants and

othersâfrom coming to cause disturbances and disorders under his sovereign residence." With this official request in hand, Cadorna ordered the two battalions to cross the bridge and take up positions in Sant'Angelo castle, in the square outside St. Peter's, and around the Vatican. He immediately telegraphed the news to the war minister, who by return wire gave his approval.

3

In the wake of the violent seizure of Rome, Lanza, Visconti, and Italy's other leaders desperately wanted to show the world that the Holy See could live in harmony with the enlarged Italian state. Nothing would be more valuable than some sign that the pope was willing to make peace with them. On September 22, Lanza sent instructions to Cadornaânow the military ruler of the occupied cityâstressing that the pope should be treated with the utmost respect. "Look into whether a visit paying homage might not be displeasing to him, so that you can express these intentions face to face in the name of the King and his government."

4

This idea, it turned out, was too much to hope for. The pope would not receive him or any other representative of the usurper king.