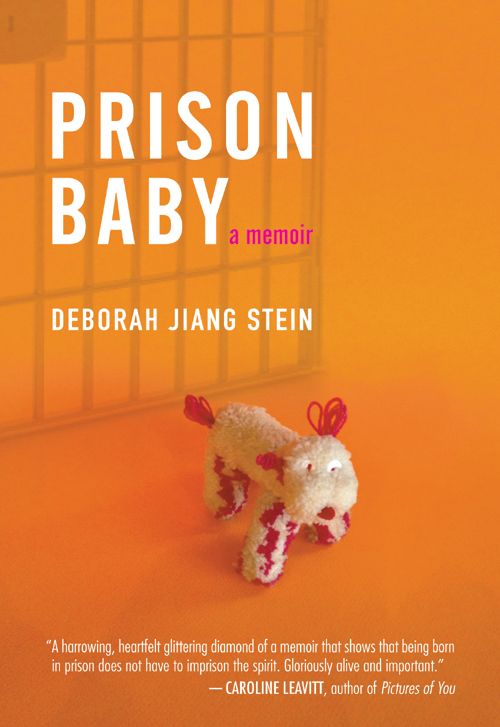

Prison Baby: A Memoir

Read Prison Baby: A Memoir Online

Authors: Deborah Jiang Stein

Praise For

Prison Baby

“

Prison Baby

hits all the emotions of the who, what, where, when and why of adoption right on the head of the nail! Some real deep life stuff is in these pages. It stirs the soul. . . . If you want to know the truth about finding who you really are, this is the story! Adopted or not.”

—Darryl “DMC” McDaniels,

adoptee and founder of the hip-hop group Run-DMC

“Deborah Jiang Stein has beaten the cycle of intergenerational incarceration, despite the odds against her—multiracial, born in a federal prison to a heroin-addicted mother. Her story offers hope to the possibility of personal transformation for anyone. No punches pulled. Deborah is evidence of the magnificent resilience of the human spirit.”

—Sister Helen Prejean,

author of

Dead Man Walking

and Pulitzer Prize nominee

“

Prison Baby

, one woman’s profound quest for family and identity, is also a soul-stirring call to arms on behalf of incarcerated women and their children. It’s a story of lost-and-found, conflict-and-peace, and proof that—with love, forgiveness, and support—people really do change their lives.”

—Tayari Jones,

author of

Silver Sparrow

“A profoundly moving search for identity,

Prison Baby

is as inspiring as it is haunting. Deborah Jiang Stein’s bold and intrepid honesty will speak to anyone who has struggled with grief, forgiveness, and finding his or her place in the world.”

—Katrina Kittle,

author of

The Blessings of the Animals

“At a time when more and more women are being incarcerated worldwide, Deborah Jiang Stein’s story of the secrets and ignominy surrounding her prison birth gives readers a brave account of the backlash children and society encounter when families are torn apart by addiction, prison, and shame. More than anything, Deborah’s book is a call for an open-eyed examination of our broken criminal justice system and a heartfelt plea for more compassionate responses to poverty and mental illness.”

—Naseem Rakha,

author of

The Crying Tree

“

Prison Baby

is an emotionally charged, transformative story about one woman’s search for her true origins. Candid and searing, Deborah Jiang Stein’s memoir is a remarkable story about identity, lost and found, and about the author’s journey to reclaim—and celebrate—that most primal of relationships, the one between mother and child. I dare you to read this book without crying.”

—Mira Bartok,

author of

The Memory Palace

“Deborah Jiang Stein’s startling journey is impossible to forget. . . . The hidden truth of her birth spurs her into the frightening territory of drugs, crime, and addiction, a crucible from which she miraculously emerges with earned wisdom, insight, and the sheltering love of two families. The ways this woman discovers herself, via the revelation of her birth mother and her reconciliation with her adoptive mother, show us how dramatically different worlds intersect, and why those intersections are so important to who we are. The bonds of mothers and daughters separated by race, class, and even by prison prove too powerful for those formidable barriers and divisions. A powerful story.”

—Piper Kerman,

author of

Orange Is the New Black

CHAPTER SIX: From the Back of the Bus

CHAPTER EIGHT: On the Fast Track

CHAPTER ELEVEN: White-Knuckle Ride

CHAPTER TWELVE: One More Secret

CHAPTER THIRTEEN: Weeping Mother

CHAPTER FIFTEEN: The Baby Book

CHAPTER SIXTEEN: Another Letter

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: The Telegram

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: Yarn Toy—More Evidence

CHAPTER NINETEEN: Less Afraid of the Dark Corners

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE: Return to the Veiled Lady

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO: Curious and with Purpose

CHAPTER TWENTY-THREE: Freedom on the Inside

CHAPTER TWENTY-FOUR: Then, This

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE: Frozen in Time

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX: Beautiful Uncertain World

THE LETTER

SWEAT GLUES MY PALM TO THE brass knob of my parents’ bedroom door.

It’s an off-limits, by-invitation-only room, sacred, like a boudoir. We kids don’t dare go in on our own. Until today.

It’s my first breaking and entering. But what else does a twelve-year-old girl do when she’s grounded but sneak around the house?

I listen for a second at the door of their room to make sure no one’s in there and then twist the knob. A ray of Seattle’s noon sun slants through the glass of the patio door on the far side of the room. I’m glad for that door. Good thing my dad just fixed the sliding device, though. Short on patience, he isn’t much of a handyman. Things break in his hands more often than they are repaired. If my parents come in, I can slip my slim five-foot frame out the sliding door and escape.

I creep across the room, around the footboard of their bed, and face my mother’s nightstand where a bird book, two novels, and three volumes of poetry pile high against her alarm clock. Her quick-fire brain keeps her engaged in no less than three or four books and magazines at the same time, each one bookmarked midway—

Audubon News

, the Sierra Club magazine, the

New Yorker

, the ACLU newsletter, books about the history of ancient Rome and Greece, poetry.

A mechanical pencil alongside pages of my father’s typed manuscript, with scribbled notes in the margins, cover his nightstand. He keeps his dresser top bare except for a tray of pipe and cigar paraphernalia—always a Zippo lighter, pipe cleaners, a box of wooden matches, a pipe damper, and an Italian leather box with gold fleur-de-lis engraved on the outside. Inside, his Italian cufflinks crafted in gold, silver, and leather jumble together.

I tiptoe to my mother’s dresser where her clip-on earrings and a strand of pearls scatter across the top. If it weren’t for her tray of Chanel bottles and collection of perfume atomizers, I’d have to pinch my nostrils to block the reek of my father’s tobacco.

I slide open my mother’s top dresser drawer.

“Shhhh,” I whisper and grab Kittsy, our Siamese, to quiet the rattle of her purr. Then I set her down and she weaves in and out between my feet, her tail in a fast flicker around my ankles. But the sweep of her purr and her tail across my skin comfort me. She calms my nighttime monster dreams when she nuzzles on my pillow, her belly curved around my head, her almond-shaped eyes more like mine than anyone else’s in my family.

The scent of Mother’s French soap collection wafts out of her dresser drawer. Each bar, the size of a silver dollar wrapped in parchment paper, perfumes her drawers. Neat stacks of folded underwear and silk slips bunch in a pile at the back of her top drawer.

I glance through the sliding-glass door—nobody’s in sight on the other side. Mother’s in her garden where she snips dead tulip heads and prunes her rose bed. My father’s secluded in his study out back, a room connected to our detached garage. He’s always hunched over a manuscript about John Donne or Milton, deep in thought and taking long puffs on either a Cuban cigar or one of his pipes. Jonathan hotdogs on his bike somewhere in the neighborhood with his friends. He’s older than me by eighteen months and never in trouble. He leaves the back talk and smarty-pants to his little sister.

Nothing here. I nudge the top drawer closed, but a corner of white catches my eye. A crisp piece of paper peeks out from under the plastic drawer liner, printed with miniature roses.

I peel up a corner of the liner.

Lodged under silky slips, under all the softness and the scent of perfume, stashed like a rumpled stowaway in a first-class cabin, I unveil a copy of a typed letter, just a paragraph long.

My neck throbs—boom da boom—my pulse in a loud pump of anticipation all the way into my shoulder muscles. High and tight as usual, my clenched shoulder blades draw in my neck so much it aches.

Must be important if it’s hidden

. I already know I’m adopted, so the letter can’t be about that. Maybe it’s about my race, or races. No one’s explained to me why I’m caramel-colored in a white family.

My mother writes to the family attorney:

Can you please alter Deborah’s birth certificate from the Federal Women’s Prison in Alderson, West Virginia, to Seattle. Nothing good will come from her knowing she lived in the prison before foster care, or that her birth mother was a heroin addict. After all, she was born in our hearts here in Seattle, and if she finds all this out she’ll ask questions about the prison and her foster homes before we adopted her.

Impossible. Read it again

. Everything blurs.

Foster care?

I’d no idea about my life before my adoption or even how old I was at the time or where I lived before then.

I read the letter over and over, these new truths forever imprinted into my memory.

I step back a few paces from the dresser and sink into the folded comforter at the end of my parents’ bed.

Prison?

Born in prison? No one’s born in a prison

.

The worst place, the worst of the worst: prison

. And the worst people, from everything I’ve heard in cartoons and seen in magazines and heard from talk.

I tuck the paper back under the liner and float from the dresser into my parents’ bathroom and stare at myself in the mirror over their sink, my body in overload. Time and space distort inside me. I don’t know where I am. My feet seem to lift, my body and brain separated by some wedge, and I’m disconnected from my house, from my neighborhood, from Earth, from humanity.

It can’t be true. If it is, what’s wrong with me? When people find out, then what? Who loves anyone from prison?

My skin itches as if tiny ants crawl along the bones in my forearms, and I scratch so hard red streaks rise on my skin. I splash water onto my burning face but give up after a while. I can’t wash away what I know isn’t there, but I feel dirty, as if grime coats my cheeks, hot to my hands. Still, I can’t stop splashing my face to rinse the grit from my eyes. My mouth has a sour taste.

Then something sinks in. My “real” mother’s an addict and a criminal. My “real” home is a prison.

The trauma of learning about my birth sends me into a deep dive, an emotional lockdown behind a wall that imprisons me for almost twenty years. The letter forces me into an impossible choice between two mothers, two worlds far apart. One mother behind bars, a criminal, a drug addict, tugs at me, her face and voice buried deep in my subconscious. The other, the mother I face every day, the one who keeps fresh bouquets of flowers on our teak credenza, I don’t connect with this mother.

I’m not hers. Not theirs.

It’s the first and last time I read the letter, and I never see it again. I don’t need to, for every word is etched in my brain, and it’s given me all the proof I need. I’m not the daughter of parents who toss Yiddish quips back and forth, of the mother who spends her Saturday afternoons throwing clay with a pottery teacher, then comes home with darling miniature ceramic vases, the mother who writes poetry with a Mont Blanc fountain pen and uses the same to correct her students’ papers. I’m not the daughter of the mother who cans cherries and whips the best whipped cream ever, the mother who says “I love you, Pet” so many times I want to smack her, the mother who waits for me after my ballet class every Saturday.

Don’t think about it. It’s not true, none of it happened. Not even

the letter

.

Some things we need to unthink and erase, just to endure living.