Prime Time (5 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

My maternal grandmother, Sophie Seymour, holding Vanessa as a baby, 1968.

With Malcolm, my grandson, when he was about one year old.

RICHARD PHIBBS/ART DEPT

Today, almost 20 percent of the U.S. population is sixty-five or older—25 million men and 31 million women—and every year people live two-tenths of a year longer!

Think about it: At the time of our founding fathers, in the eighteenth century, the average life expectancy was only thirty-five. Since then, science, modern medicine, improved nutrition and lifestyle, sanitation, and lower maternal mortality rates have extended our life expectancy by forty-five years, from thirty-five to

eighty

! As I have said, this represents an entire second adult lifetime. The jump of thirty-four years in just the last century is truly stunning given that during the previous forty-five hundred years, from the middle of the Bronze Age to the twentieth century, human life expectancy increased by only twenty-seven years. This may be one of the most dramatic changes in contemporary times, and we have barely begun to come to terms with what it means for us individually, for the future of our society, and for the planet. From a policy and cultural point of view, we are still functioning as though this extension of life expectancy hasn’t happened. That is why Professor Arnheim’s staircase is the one we need to climb.

If we are not burdened by a debilitating disease, this is the time when we can begin to assume our essential personhood.

Freed from being so strongly defined by a uterus or penis or a taut body or a job or our relationships to our children, to a partner, to a firm or a profession, we now have at least a third of our life span still to go. In that time, we can explore life’s new potentials and deepen what we already are and what we already know.

Becoming Whole

When I wrote

My Life So Far,

I called the section about Act III “Beginning” because that is what it felt like then. Now that I am a decade into this act, I think a more fitting title for this stage would be “Becoming Whole.” To see Act III in this way, to see it as continued human development, represents a revolutionary paradigm shift. Ours is the generation to make this shift, to reinvent the last third of life, and we will do it not just for ourselves. It will represent a seismic shift for the world around us, and particularly for our children and young friends. Whether we like it or not, we have become the first role models for the younger generations of how to prepare for the last third of life. Here’s to being good role models!

The next chapter is about why doing a review of my life has changed everything for me now.

Vadim and his mother with baby Vanessa.

Grandma Sophie Seymour with baby Troy. Behind her is a wood bust of my half-sister, Frances, carved by my dad.

Holding baby Malcolm in 1999.

Vanessa trying to get a tuxedoed Malcolm to look at his grandmother presenting an Oscar in 2000.

CHAPTER 2

A Life Review: Looking Back

to See the Road Ahead

He is the happiest man who can see the connection between the end and the beginning of his life.

—GOETHE

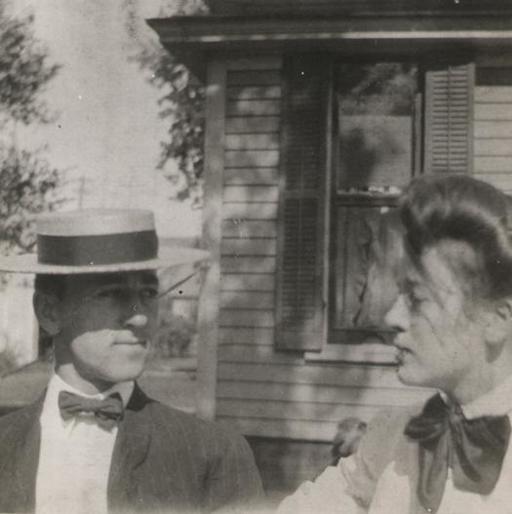

Dad’s father and mother, close up.

O

NE OF THE SMARTEST THINGS I EVER DID—AND I CAN SAY this unequivocally—was a life review. I examined myself and my life in Acts I and II as carefully and honestly as I could, as a way toward wholeness and to prepare for a good Act III. By doing a life review, I gradually began to see myself, as well as certain events and people in my past, with new eyes. It wasn’t the facts of them that changed; it was the meaning they held for me. I was able to see my younger self in a new way—with both more compassion and more objectivity. The quality of my relationships to certain people and events in my past—my mother and father, especially—was also transformed, as was how I feel about myself now. In a way, I discovered the feisty, strong girl I had always been.

The Meaning We Assign to Our Lives

Only recently, while reading

Man’s Search for Meaning,

by the psychiatrist Viktor Frankl, did I understand why my personal life review had such an effect on me. Frankl, who spent many years in a Nazi concentration camp, came to the conclusion that everything you have in life can be taken from you except one thing: your freedom to choose how you will respond to a situation. That, I now believe, is what determines the quality of the life we have lived—not whether we’ve been rich or poor, famous or unknown, healthy or ill. What determines our quality of life is

how we relate to these realities:

what kind of meaning we assign them, what kind of attitude we cling to about them, what state of mind they trigger.

Act I: Me at age three.