Prime Time (16 page)

Authors: Jane Fonda

Tags: #Aging, #Gerontology, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses - United States, #Social Science, #Rejuvenation, #Aging - Prevention, #Aging - Psychological Aspects, #Motion Picture Actors and Actresses, #General, #Personal Memoirs, #Jane - Health, #Self-Help, #Biography & Autobiography, #Personal Growth, #Fonda

I returned to Turks and Caicos four months later for a second try. “Slow down” was my mantra this time, and together with my already-scuba-certified daughter and son, I made two successful dives to eighty-five feet. I descended at a pace that seemed preposterously slow, but I wasn’t about to fail again! The sheer joy of swimming with my children along a spectacular coral shelf among reef sharks, stingrays, barracudas, sea turtles, and many colorful fish was the big payoff, and I learned a big life lesson: This is the stage of life where there is less room for ego and more need for humility, balance, and common sense.

In

Women Coming of Age,

I included a photo of a woman in her eighties jogging with her daughter. I was utterly confident that that’s how I would be when I got to that age. Well, I’m ten years younger than she was, and I haven’t been able to jog for nearly a decade! My replaced hip and knee won’t let me. But I’ve found that that’s okay, just so long as I do

something.

It would have been easy to stop exercising after my hip surgery, or because my knees sometimes hurt due to osteoarthritis. For a while I felt sure I’d never be able to do anything close to what I had done before. But when, mostly for vanity reasons, I started up again, I soon discovered that moving, walking, swimming, lifting light weights, and stretching made my muscles and joints feel much better. It was when I was inactive that the arthritis got worse—and so did my mood.

I don’t jog anymore or do anything else that overly stresses my joints. Even downhill skiing is out. But I’ve gotten into snowshoeing, and this slower, more meditative, but equally aerobic sport is, for me, perfectly suited to the Third Act.

Since I’m not in the snow very often, what I do to burn calories and stay aerobically fit is walk briskly (anywhere) or hike (when I’m in the country and the weather’s nice) for an hour, five or six days a week. When the weather is too hot or too cold, I go to a gym and get on a recumbent bike or an elliptical trainer (the kind that works the arms as well as the legs). I’ll go for thirty minutes, switching every ten minutes from one machine to the other to ease the boredom.

Occasionally I replace walking with swimming for thirty minutes, and when I do, I protect my neck by wearing a well-fitted mask and snorkel, which eliminates the need to turn my head every few strokes to catch a breath. It also makes it easier for me to go into a meditative state without worrying about bumping into the ends of the pool.

Me, hiking a steep hill.

Snorkeling in the Galapagos.

Too many people—men, especially—will stop physical activity altogether if they are no longer able to do things the way they did when they were younger. This is a real mistake. It’s far better to keep active, but at a lower level. And if, for some reason, you have been unable to work out for a time, be careful when you start up again. I always make sure to cut back a notch rather than trying to pick up where I left off. Older people hurt themselves trying to go from inactivity to sudden, challenging activity, like deciding to play basketball with the grandchildren one weekend. Instead, you want to try to establish a regular routine of a minimum of twenty minutes of some sort of aerobic activity at least three times a week.

The Exercise Imperative

I have realized over the last decade that the difference between a younger person who is physically active and one who isn’t is not particularly dramatic. But the difference between an older person who is active and one who isn’t is enormous. “Fitness for the young person is an option,” says expert on aging Dr. Walter Bortz, “but for the older person it is an imperative.”

1

Younger people’s bodies are more resilient and forgiving, whereas older bodies are weakening; unless we deliberately intervene to slow this process down (or, yes, even reverse it), we risk sliding into early decrepitude. It is largely up to us. The human body is fully capable of vigorous use well into the nineties and even longer.

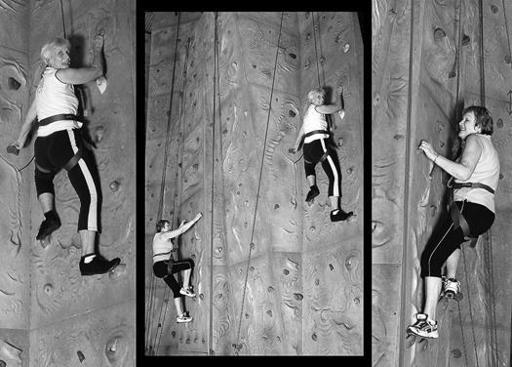

ANNA-MAREE HARMAN,

[email protected]

A group of seniors, all part of Tewantin-Noosa R&SL club, made a calendar and sent it to me. This was the cover!

ANNA-MAREE HARMAN,

[email protected]

In his book

The Blue Zone: Lessons for Living Longer from the People Who’ve Lived the Longest,

Dan Buettner visits places in the world where large numbers of people live past one hundred: Sardinia, Okinawa, Costa Rica, and Loma Linda, California. One of the things all of them have in common is daily, low-intensity physical activity such as walking, hiking, and farming. Activity strengthens the heart and bones, improves the circulation, reduces obesity, thickens the skin, and can help with depression because of the endorphins released into the system. I learned from years of watching exercise change women’s bodies and minds that it is also empowering: It gives you a sense of being in charge of yourself and your well-being, which is particularly important for older people, who often feel they aren’t in charge of much of anything anymore.

“Use it or lose it” is a truism, but what it leaves out is that

if it’s lost, we can get it back.

Not only can we recover lost functions but, as Dr. Bortz notes, “in some cases we can actually

increase

function beyond our prior level.”

2

How Active Does “Being Active” Mean?

Don’t worry, it doesn’t have to be scary. In fact, “Easy does it” is the appropriate mantra. I never thought I would say this, old go-for-the-burn me. But I’ve learned the hard way to respect that I am no longer the Jane Fonda who created the original Workout. My body will make me suffer if I don’t slow down. This is why I created the new Jane Fonda’s Prime Time line of exercise DVDs for boomers (people born during the demographic birth boom between 1946 and 1964) and seniors (those born prior to the end of World War II) who, like me, need to take it a little easier.

Let’s discuss all the components of a good weekly exercise regimen—aerobics, resistance, balance, and stretching—and why these are especially vital for people over fifty.

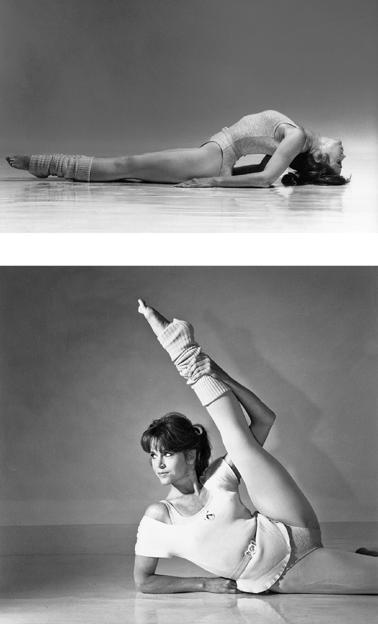

In the early 1980s, I was in my midforties and I had just launched my workout studio.

PHOTOS BY HARRY LANGDON

Why Is Aerobic Activity Important?

Aerobic activity is important on many levels and, certainly, is critical to one’s overall health. But right now, we’ll begin with weight loss. Aerobic activity is the only thing that gets rid of fat from all over your body, including the marbled fat deep inside your muscles; dieting alone can’t do this. In fact, for permanent body-fat weight loss (as opposed to fluid or muscle weight loss), the combination of reducing calories (from unhealthy food) together with aerobic exercise is the answer.

Aerobics for Your Heart

Heart disease is the primary cause of death in older men and women, killing one in four. How well our cardiorespiratory system functions is one of the best clues to our overall fitness, and something we can have considerable control over, even if we are genetically predisposed to heart disease. In fact, aerobic exercise can influence whether the genes for heart disease, diabetes, or other illnesses are ever activated. Understanding the importance of cardio fitness, including what can go wrong, helps us understand why aerobic exercise is so important.

The cardiorespiratory system is responsible for delivering blood, which carries oxygen and nutrients, to every cell in the body, and for carrying away carbon dioxide and other waste products. This is the system that supplies the muscles with the oxygen essential for burning calories for energy. It determines our “maximum aerobic capacity,” or V0

2

max, as it’s known in sports circles. This is one of the most critical measures of our body’s performance: how much oxygen we take in; how much blood is pumped, and with what degree of ease, throughout the body; and how well oxygen is taken up and utilized by the muscles and other cells. These dynamics are a master key to our vitality.

With age, the heart and the circulatory system gradually begin to lose some of their effectiveness. After age thirty, there is an average decline of about 1 percent a year in our V0

2

, or aerobic, capacity. The lungs are less elastic and, because they can accept less air, transfer less oxygen into the blood. The heart muscle and the blood vessels thicken and become more rigid, which means that each stroke of the heart pumps less blood. Inelastic and narrowed arteries cause the heart to work harder to move blood from the chest to the head, arms, and legs. As the heart pushes the blood more forcibly through the circulatory network, our blood pressure tends to rise.

All of this is common and needn’t mean a loss of basic health, provided we don’t also become sedentary. Inactivity increases the likelihood that fatty plaque will begin to cling to our arterial walls, causing atherosclerosis and chronic hypertension, which can spiral into a heart attack or, if the brain is involved, a stroke. Atherosclerosis, hypertension, heart attack, and stroke combined account for half of all disabling health problems in women and men alike.