Pox (48 page)

Authors: Michael Willrich

EIGHT

SPEAKING LAW TO POWER

It is one of the more ennobling characteristics of the American system of government that the greatest of constitutional questions may arise in the most humble of places. A coach on a Louisiana train. An elementary school in Topeka, Kansas. A pool hall in Panama City, Florida. The seminal case in modern American public health law began at the threshold of a tenement house apartment in a neighborhood filled with wage earners and immigrants.

1

1

On March 15, 1902, Dr. E. Edwin Spencer, chairman of the Cambridge, Massachusetts, Board of Health, called upon Pastor Henning Jacobson in his apartment at 95 Pine Street, in the neighborhood of Cambridgeport, about a mile east of Harvard Yard. A man little known beyond his Swedish congregation at the nearby Augustana Lutheran Church, Jacobson lived with his wife, Hattie, and their sons Fritz, David, and Jacob. Spencer had practiced medicine in Cambridge for thirty years and headed the board of health for almost ten of them. Spencer informed Jacobson of the board's “vote” declaring smallpox prevalent in the city and ordering all inhabitants who had not been vaccinated within the past five years to submit to the procedure at once or incur a $5 fine, as provided for by the Massachusetts compulsory vaccination law. The penalty was not trivial: the average weekly wage of an American factory worker was about $13, and it is unlikely that an immigrant minister earned much more than that. Jacobson, forty-five, had not been vaccinated since childhood. Spencer offered to vaccinate him “then and there,” free of charge. But Jacobson “absolutely refused.” He was later summoned to court, tried, and found guilty of “the crime of refusing vaccination.” Rather than pay his fine, Jacobson appealed.

2

2

During the next three years, Pastor Jacobson would pursue his cause all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, prompting the Court's first ruling on the subject of compulsory vaccination. In the words of Justice John Marshall Harlan, who wrote the opinion for the majority in

Jacobson v. Massachusetts

, the minister claimed that “a compulsory vaccination law is unreasonable, arbitrary, and oppressive, and, therefore, hostile to the inherent right of every freeman to care for his own body and health in such way as to him seems best.” More than a century on, it is difficult to appreciate just how radical that claim must have sounded when first uttered. Henning Jacobson was asking the nation's highest court to contemplate the true extent of constitutional liberty in the United States.

3

Jacobson v. Massachusetts

, the minister claimed that “a compulsory vaccination law is unreasonable, arbitrary, and oppressive, and, therefore, hostile to the inherent right of every freeman to care for his own body and health in such way as to him seems best.” More than a century on, it is difficult to appreciate just how radical that claim must have sounded when first uttered. Henning Jacobson was asking the nation's highest court to contemplate the true extent of constitutional liberty in the United States.

3

The

Jacobson

case marked the end of the great wave of smallpox epidemics that had swept across the United States at the turn of the century. It also signaled the beginning of the long struggle to reconcile twentieth-century Americans' ever-increasing expectations of personal liberty with the far-reaching administrative power needed to govern a modern, urban-industrial society.

Jacobson

case marked the end of the great wave of smallpox epidemics that had swept across the United States at the turn of the century. It also signaled the beginning of the long struggle to reconcile twentieth-century Americans' ever-increasing expectations of personal liberty with the far-reaching administrative power needed to govern a modern, urban-industrial society.

Â

Â

A

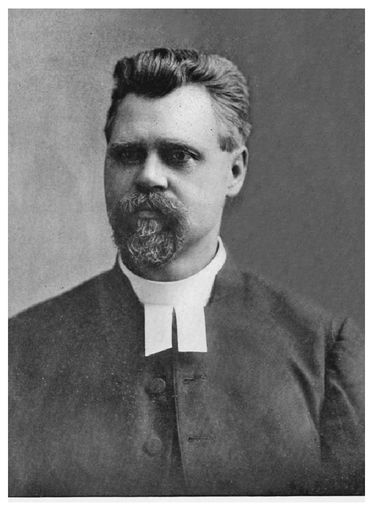

man in his prime, with deep-set eyes and a touch of gray in his beard, Henning Jacobson was an unlikely troublemaker. He was an institution builder, the spiritual leader of the Swedish American community of eastern Massachusetts.

man in his prime, with deep-set eyes and a touch of gray in his beard, Henning Jacobson was an unlikely troublemaker. He was an institution builder, the spiritual leader of the Swedish American community of eastern Massachusetts.

Born in rural Yllestad, Sweden, in 1856, he had immigrated to America with his family in 1869. The Jacobsons' adopted country was in the throes of its postâCivil War Reconstruction and just entering the explosive period of growth that would make it the world's most productive industrial economy by 1900. As a young man, Jacobson took out naturalization papers and became a U.S. citizen. He studied at Augustana College in Rock Island, Illinois, an institution founded by Swedish Lutheran immigrants in 1860 to prepare young men for the ministry. Jacobson founded the college orchestra. He played the contrabass, anchoring the music with deep-pitched authority.

4

4

Swedish Lutheranism was not a radical religious sect. It was the official state church of Sweden, the faith of the overwhelming majority of Jacobson's countrymen who migrated to the United States during the peak decades of Swedish immigration after the Civil War. Jacobson received his ordination in Kansas, in the rural heartland of Swedish America. But his future lay in an eastern industrial city. The Church of Sweden Mission Board called him in 1892 to build the Augustana Lutheran Church in Cambridge. He conducted services in his native tongue and became a regular at the Boston docks, meeting newly arrived Swedes and taking them back to Cambridge, where he helped them find jobs and homes. He would remain pastor of the Cambridge church until his death in 1930.

Nothing in the conservative biblical doctrine of Swedish Lutheranism dictated defiance to vaccination, but Jacobson practiced a form of pietism that filled the daily details of life with religious significance. His brief to the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Courtâwritten by his lawyers but submitted under his nameâdecried compulsory vaccination as an unconscionable state sacrament. “We have on our statute book,” it said, “a law that compels such a man to offer up his body to pollution and filth and disease; that compels him to submit to a barbarous ceremonial of blood-poisoning.”

5

5

That reference to blood-poisoning held a literal meaning for Jacobson. Though antivaccinationism ran rife in the Swedish countryside, he had undergone vaccination as a child, in accordance with national law. Early childhood vaccination spread quickly in Sweden after 1800 and became compulsory in 1816ânearly forty years before Massachusetts enacted America's first vaccination law. Sweden was an international public health success story, championed in the American medical literature. Smallpox killed 300,000 people in the country between 1750 and 1800, most of them children. Mortality levels fell sharply after the introduction of vaccination, and by 1900 the disease had virtually disappeared. But young Henning's vaccination had gone badly. He experienced “great and extreme suffering” that instilled in him a lifelong horror of the practice. Henning and Hattie Jacobson knew all too well the perils of a nineteenth-century childhood. Married for eighteen years by the time a U.S. Census-taker knocked on their door in 1900, they had created five children together, but only three survived. One of Jacobson's boys (he did not say which) suffered adverse effects from a childhood vaccination, convincing the minister that some hereditary condition in his family made vaccine a particular hazard for them. Jacobson's belief that smallpox vaccine threatened his family's existence seemed as deeply ingrained as his religious faith.

6

6

Pastor Henning Jacobson, circa 1902.

COURTESY OF THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH IN AMERICA

COURTESY OF THE EVANGELICAL LUTHERAN CHURCH IN AMERICA

Â

If Jacobson made an unlikely rabble-rouser, neither did the man who stood across his threshold that March day fit the part of the heartless bureaucrat. E. Edwin Spencer had a starkly different medical background and leadership style from his counterpart across the Charles River, Chairman Samuel Durgin of the Boston Board of Health. Unlike the Harvardeducated Durgin, Spencer had studied a form of alternative medicine. Born to a Rhode Island farming family in 1833, he graduated from the Eclectic Medical College in Cincinnati, a young institution that considered itself a citadel of freedom in medical education. The eclectics favored botanical remedies, eschewing “heroic” interventions and mercurial medicines. Spencer moved to Massachusetts and received another degree from the short-lived Worcester Medical College, an eclectic school that received its charter from the state in 1849 over strenuous professional opposition. He settled in Cambridge, where he practiced medicine, held the office of city physician, and earned an appointment to the board of health.

7

7

Working in a field dominated by allopathic physicians, Spencer never severed his ties to “irregular” medicine. A onetime president of the Massachusetts Eclectic Medical Society, he remained an officer of that organization until his death in 1903. Unlike many eclectics, Spencer believed in the theory of vaccination. But he showed a marked reluctance to impose the beliefs of the mainstream medical profession upon unwilling members of the public. It is hard to imagine Spencer relishing a public confrontation with Immanuel Pfeiffer. In his interactions with Jacobson, Spencer proceeded with caution and deliberation, as he had ever since smallpox first broke out in Cambridge several months earlier.

Smallpox had already been spreading for months in Boston and other cities of eastern Massachusetts by the time Cambridge reported its first case on October 25, 1901. The outbreak, in a tenement by the Charles River, still caught the city unprepared. Despite the entreaties of the board of healthâa three-member board consisting of Dr. Spencer and two laymen, lawyer William Peabody and engineer Charles Harrisâthe city government had balked at spending taxpayer money on precautionary measures. Cambridge had no pesthouse, and in recent years vaccination had fallen off. Harvard required all of its students and employees, from the professors to the African American waiters at Memorial Hall, to get vaccinated; during the months to come the university reported not a single case of smallpox. But Harvard and the elite bastions of Brattle Street and Avon Hill stood as islands of privileged homogeneity in a diverse city of 95,000 people that teemed with brickworks, factories, and thickly settled neighborhoods. By the end of December, the city suffered fifteen smallpox cases, three of them fatal.

8

8

Spencer's response was decisive but temperate. The board established a pesthouse on New Street, near the Fresh Pond marshes, and opened public vaccination stations, where thousands of citizens lined up for free vaccine. The voluntary vaccination effort hit a setback on January 4, when the

Cambridge Chronicle

reported that Annie Caswell, just five years old, had “died of tetanus, or lockjaw, following vaccination.” The news came less than one month after the last Camden, New Jersey, child had died from postvaccination tetanus. According to the report, the doctors who had tried to save Annie believed “the vaccine used might have been impure or that some foreign substance may have gotten into the sore.” Dr. Edwin Farnham, the chief inspector for the Cambridge Board of Health, swiftly declared his belief that vaccination could not have caused Annie's death. There would be no investigation.

9

Cambridge Chronicle

reported that Annie Caswell, just five years old, had “died of tetanus, or lockjaw, following vaccination.” The news came less than one month after the last Camden, New Jersey, child had died from postvaccination tetanus. According to the report, the doctors who had tried to save Annie believed “the vaccine used might have been impure or that some foreign substance may have gotten into the sore.” Dr. Edwin Farnham, the chief inspector for the Cambridge Board of Health, swiftly declared his belief that vaccination could not have caused Annie's death. There would be no investigation.

9

As the outbreak of smallpox continued, with twenty-six cases and three more deaths reported during January and February 1902, the board declined to use its full powers. Spencer publicly defended his cautious quarantine policy, saying the city had “no right” to placard the home of a resident merely because she may have been exposed to smallpox. The board must be “absolutely certain” the resident had been infected. And the board held on to compulsory vaccination as a last resort.

10

10

Spencer seemed determined to avoid the sort of public standoffs with antivaccinationists that the more aggressive actions of Durgin's Boston board had sparked in the streets, the criminal courts, and the State House. That January, as the Boston virus squad stepped up enforcement in working-class neighborhoods, the doctors and police had run up against many determined refusers, including nineteen residents willing to face prosecution rather than submit.

11

11

Charles E. Cate, a South End laborer, refused vaccination even as his wife lay sick in the Southampton Street pesthouse; he served fifteen days in Charlestown Jail rather than pay his $5 fine. As a force of 125 city-employed physicians moved from house to house in East Boston, vaccinating five thousand residents in a single day, a Canadian-born grocer named John H. Mugford refused to allow Dr. John Ames to vaccinate him or his daughter, Eva. Dr. Ames assured Mugford that the vaccine points he carried, on small quills, were perfectly safe. But Mugford did not relent. “I told him I studied the question too long to allow any poison to be put into my system,” the grocer testified at his trial. The court found Mugford guilty on both charges of refusing vaccination. He appealed his case to the Supreme Judicial Court.

12

12

Even when Spencer's Cambridge board finally took steps to enforce vaccination, it moved with an exceptional degree of caution. The board ordered vaccination on February 27, 1902. Spencer waited two more weeks before dividing the city into districts and sending seventeen physicians from house to house to vaccinate “all the inhabitants they could find.” Thousands were vaccinated in this way, while better-heeled citizens paid their family doctors to perform the procedure. For the city vaccinators, finding the inhabitants was not always easy. Some bolted. Others shooed the doctors from their doorsteps. The board compiled a catalogue, containing a card for every house in a large swath of the city. Each card listed the names of the inhabitants and the date each had last been vaccinated. Vaccine refusers were noted. Among them were Albert M. Pear, a prominent city official, and Pastor Henning Jacobson, whom Spencer visited himself. The board prosecuted no one.

13

13

Other books

The Hidden Force by Louis Couperus

People Park by Pasha Malla

The Proud Tower by Barbara Tuchman

Light Years by James Salter

Tek Kill by William Shatner

Prey (BookStrand Publishing Romance) by Mary Lou George

The Demented Z (Book 3): Contagion by Thomas, Derek J.

Until We Meet Once More by Lanyon, Josh

Great Exploitations (Crisis in Cali) by Williams, Nicole

Organized for Murder by Ritter Ames