Pox (17 page)

Authors: Michael Willrich

Any

epidemic of smallpox would have caught most southern communities off guard. But the epidemiological profile of these end-of-the-century epidemics made them particularly difficult to manage. Smallpox struck African Americans first. And the disease took an exceptionally mild form. These two facts shaped how the scientific claims and political demands of public health officials would be received by the South's many publics.

epidemic of smallpox would have caught most southern communities off guard. But the epidemiological profile of these end-of-the-century epidemics made them particularly difficult to manage. Smallpox struck African Americans first. And the disease took an exceptionally mild form. These two facts shaped how the scientific claims and political demands of public health officials would be received by the South's many publics.

Â

Â

A

ddressing a white Mississippi audience in the early twentieth century, Booker T. Washington told his listeners, as he so often did, that “the destiny of the southern white race” was “largely dependent on the Negro.” The eminent African American educator drew upon recent history to make his point. “You can't have smallpox in the Negro's home and nowhere else,” he said. “You need to see that the cabin is clean or disease will invade the mansion. Disease draws no colour line.”

46

ddressing a white Mississippi audience in the early twentieth century, Booker T. Washington told his listeners, as he so often did, that “the destiny of the southern white race” was “largely dependent on the Negro.” The eminent African American educator drew upon recent history to make his point. “You can't have smallpox in the Negro's home and nowhere else,” he said. “You need to see that the cabin is clean or disease will invade the mansion. Disease draws no colour line.”

46

Several years earlier, C. P. Wertenbaker stood outside a grocery store in Richland, Georgia, a whistle-stop town of nine hundred souls not far from the Alabama border. As people came and went from the store, a crowd of children, white and black, loafed outside. One African American boy caught Wertenbaker's eye. Judging by the scabs on his face, Wertenbaker figured the boy to be in the convalescent stage of smallpox known in the medical literature as “desquamation.” Smallpox experts considered desquamation, when the scabs crumbled and fell from the face and body, to be the most contagious phase of the disease. The boy, Wertenbaker recalled, was “scattering infection everywhere he went.” No one paid the boy any mind.

47

47

It was never easy to get rural people to take mild smallpox seriously, but when the disease appeared to infect “none but negroes” the task proved far more difficult. Federal, state, and local health officials, reporting from points across the South, uniformly identified the African American population as the reservoir for this disease. Newspapers, too, traced local outbreaks to particular African American individuals, families, or settlements. Even after the disease made its appearance among whites, the great majority of reported cases were in black people. In Tennessee and North Carolina, African Americans accounted for three quarters of all reported cases, far exceeding their proportion in the population. In particular locales, officials recorded far greater disparities. In Greenwood, Mississippi, a town of three thousand inhabitants where blacks outnumbered whites by a narrow margin, more than five hundred people contracted smallpox in the winter of 1900; just twenty-three of them were white.

48

48

Wertenbaker observed that many white Southerners, including some physicians, called mild smallpox “nigger itch” and claimed that whites could not catch it. Often, the first whites to contract the disease aroused contempt. When a group of young white men in Stanford, Kentucky, broke out with the “itch,” their neighbors had a ready explanation: the boys had made “indiscreet visits” to the “Deep Well Woods,” an African American settlement on the outskirts of town. The first white patients identified in health board reports were usually marginal figures such as tramps, half-witted women, and promiscuous girlsâfixtures of the era's eugenics-inspired literature on southern “white trash.” That some rural whites covered their faces before allowing health board photographers to take their pictures attests to the shame they felt at being caught with this “loathsome negro disease.”

49

49

Southern health officials admitted that a large percentage of smallpox cases went unreported in their states. How, then, could they speak with such certainty about the racial origins of these epidemics? Those in a position to produce official accounts of epidemics have often blamed their occurrence on subordinate social groups. But this is not to say that all such narratives are works of pure fiction. To dismiss the official accounts out of handâor to read them only as elite ideologyâis to forgo all hope of recovering the social experience of disease. The wonderfully idiosyncratic epistolary form that public health reports took in this era inspires at least some confidence in their contents. State reports consisted mainly of letters and telegrams, peppered with chatty detail, sent in by local health officers. Even assuming broad agreement regarding matters of race and class, it would have taken a racial conspiracy of an implausible scale to make all of these reports tell a common story of the epidemic's prevalence among African Americans and poor whites, if there were not some basis for this in fact. With an infectious disease such as smallpox, which spread most easily among people without regular access to medical care and who lived in close proximity to one another, the poorest members of society were exceptionally vulnerable. Inadequate nutrition made poor people susceptible to all sorts of diseases. Public health officials made a revealing leap, however, when they concluded from such epidemiological facts that “irresponsible negroes” (or “ignorant” whites) were morally culpable for the spread of smallpox.

50

50

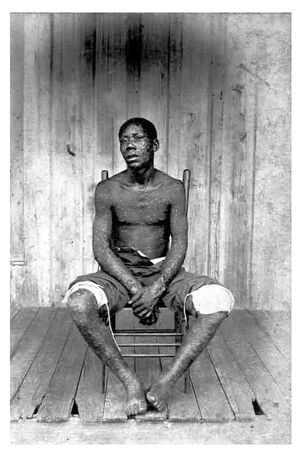

Smallpox patient at the Tampa pesthouse, 1900.

COURTESY OF THE STATE ARCHIVES OF FLORIDA

COURTESY OF THE STATE ARCHIVES OF FLORIDA

Â

In his personal papers and public writings, C. P. Wertenbaker was serious, dispassionate, and reservedâa gentleman scholar of the Service stripe. In his field reports to Washington, he dutifully noted whites' belief that they had a natural immunity to the disease they called “nigger itch,” but he considered this popular belief a sign of ignorance and a bane to scientific smallpox work. He did not normally indulge in expansive statements of racial ideology, “scientific” or otherwise. But in one letter, which he sent to a Mississippi health official in 1910, the federal surgeon revealed some of his assumptions about the state, and fate, of African American health. “There is no question in my mind,” Wertenbaker wrote, “but that the negro constituted the gravest menace to the country in which they lived, from a sanitary standpoint.” “The negro is like a child,” he continued, “incapable of carrying on any effectual sanitary work unless guided and directed by the white people.... Unless there is a marked change in sanitary conditions among the negroes, I believe that within the next 100 years the negro will be almost as scarce in this country as the Indian now is. I believe that the extinction of the race is imminent.”

51

51

With those few lines Wertenbaker revealed a cast of mind entirely conventional among white medical authorities of his time and place. Such theories had a long lineage. In the antebellum period, southern medical writers had used just such claims to defend the institution of slavery. Observing that African American slaves were less prone than whites to contract malaria and yellow fever (because, we now know, of an inherited genetic resistance to the mosquito-borne viruses that caused those diseases), slaveholders lauded their chattels' natural fitness for back-breaking labor in the coastal rice and cotton fields. Ideologues claimed the intelligence and moral dispositions of African Americans were so deficient that slaves needed their white masters' protection and restraint. In the postâCivil War era, white medical experts ridiculed the freed people's claims to equal citizenship. During the 1890s and 1900s, physicians interpreted African Americans' high mortality and morbidity rates as evidence of black people's supposed biological inferiority, insisting that they brought disease upon themselves by sexual vices and intemperance. Using the flawed late nineteenth-century census returns to bolster their case, white experts claimed that the health of African Americans had plummeted since emancipation. This proved, the authorities claimed, that blacks had benefited from slavery and were so ill suited to freedom that they were now destined for extinction. Such medical racism led leading life insurance companies to refuse policies to African Americans.

52

52

In

The Philadelphia Negro

(1899), his pathbreaking work of urban sociology, the young African American scholar W. E. B. Du Bois calmly showed that the prevailing theories of African American health rested on sloppy science and wishful thinking. Since little reliable data existed regarding African American health during slavery, Du Bois pointed out, claims that the health of the race had undergone a dramatic decline since emancipation were, at best, unsubstantiated. Of the myth that blacks were doomed for extinction, Du Bois wrote that it represented “the bugbear of the untrained, or the wish of the timid.” But such medical falsehoods had devastating consequences. They inured the nation to the realâand substantially preventableâhealth problems of poor African Americans in the North and South. The average life expectancy for blacks was thirty-two, compared to nearly fifty for whites. Infant mortality rates were shockingly high. Black men and women were disproportionately struck by many chronic and infectious diseases, including heart disease and consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis), a major killer in the African American population. “In the history of civilized peoples,” Du Bois wrote, rarely had so much “human suffering” been viewed with “such peculiar indifference.”

53

The Philadelphia Negro

(1899), his pathbreaking work of urban sociology, the young African American scholar W. E. B. Du Bois calmly showed that the prevailing theories of African American health rested on sloppy science and wishful thinking. Since little reliable data existed regarding African American health during slavery, Du Bois pointed out, claims that the health of the race had undergone a dramatic decline since emancipation were, at best, unsubstantiated. Of the myth that blacks were doomed for extinction, Du Bois wrote that it represented “the bugbear of the untrained, or the wish of the timid.” But such medical falsehoods had devastating consequences. They inured the nation to the realâand substantially preventableâhealth problems of poor African Americans in the North and South. The average life expectancy for blacks was thirty-two, compared to nearly fifty for whites. Infant mortality rates were shockingly high. Black men and women were disproportionately struck by many chronic and infectious diseases, including heart disease and consumption (pulmonary tuberculosis), a major killer in the African American population. “In the history of civilized peoples,” Du Bois wrote, rarely had so much “human suffering” been viewed with “such peculiar indifference.”

53

That indifference was not just a cultural phenomenon. It was a systemic feature of the white-dominated medical profession, especially in the South. Reputable physicians refused to treat African Americans. As southern cities built new public hospitals in the late nineteenth century, most excluded blacks or relegated them to inferior Jim Crow wards. Such demeaning treatment, Du Bois observed, intensified the “superstitious” fear of hospitals and medicine that he considered “prevalent among the lower classes of all people, but especially among Negroes.” As a consequence, most poor blacks did not seek medical aid from a white physician until they were desperately ill. “Many a Negro would almost rather die than trust himself to a hospital.”

54

54

The best hope for African American health care lay with the black medical profession. By 1900 more than 1,700 black physicians practiced in the United States, up from about 900 a decade earlier. African American medical schools, nursing schools, and hospitals opened during the same period. Industrial schools such as Booker T. Washington's Tuskegee Institute instructed poor blacks in the use of toothbrushes and everyday hygiene. As significant as these developments were, they could not quickly correct a pattern of institutional neglect so long in the making. As late as 1910, the entire state of South Carolina had only 66 professional black physicians, or one physician for every 12,000 black people. The ratio for white people was about 1 to 800. African American professional medicine existed mainly in urban areas. In the rural South, where most African Americans lived, black physicians were scarce. When rural blacks took ill, they still relied, as they had during slavery, on the informal medical knowledge of friends and relatives, root doctors, and practitioners of magical medicine. In a period of explosive growth in the American medical profession, it remained all too common for African Americans to take ill, suffer, and die without receiving any medical attention.

55

55

Even in an era of such systemic neglect, the realization that smallpox was spreading among African Americans across the South was bound to cause alarm among white public health officials. White officials understood from their own observations in the field that smallpox spread like wildfire through unvaccinated populations, regardless of their color. Since the majority of Southerners, white and black, had never been vaccinated, officials made some effort to explain the early prevalence of the disease among blacks.

White medical commentators marveled at African Americans' sociability: their “gregarious habits,” their fondness for going on “excursions” and mingling “promiscuously,” their “close association and intermixing.” And the commentators were not just talking about sex. Many fretted about “religious negroes,” who seemed ever to be gathering in one meeting or another. During an outbreak, African American churches were usually among the first places quarantinedâright after the black schools. Even the playfulness of African American children was deemed a threat to the public health. In the autumn of 1899, as sharecroppers in Concordia Parish, Louisiana, brought in the harvest, piling the seed cotton high in their cabins, one white official worried that children would pollute the cotton with smallpox: “On this inviting heap the darky children romp by day and sleep by night with that habitual disregard of cleanliness characteristic of the race.” The writer knew he could count on his readers' imagination to complete the scenario. With the infected cotton bound for market, and from there to the mills, and from the mills to the homes of unsuspecting white consumers, who could say how far smallpox would travel from those sharecroppers' shacks?

56

56

Racial anxieties permeate the official record of the southern epidemics. But the record also contains clues about the deeper causes of the prevalence of smallpox among African Americans. While poor nutrition and overcrowded living conditions made black people especially susceptible to smallpox, institutionalized racism fostered African Americans' long-standing distrust of white doctors. Neglected and mistreated by the medical profession, the vast majority of southern blacks had never been examined by a physician, let alone been vaccinated, and would just as soon keep it that way. African Americans were understandably reluctant to report cases of smallpox in their homes or neighborhoods to white authorities. As the

Atlanta Constitution

noted during the Birmingham epidemic, “[T]he negroes there have a great dread of the pesthouse and use every effort to avoid having their friends and relatives taken there.” In other places, the physical or cultural distance from white medical authority was so great that such subterfuge was unnecessary. Traveling through Georgia in 1899, Wertenbaker kept stumbling upon African American settlements or sections of towns with names like “Hell's Half Acre,” where smallpox had spread for four or five months, sometimes longer, without attracting the least notice from whites. “The disease became epidemic before it was known,” he said.

57

Atlanta Constitution

noted during the Birmingham epidemic, “[T]he negroes there have a great dread of the pesthouse and use every effort to avoid having their friends and relatives taken there.” In other places, the physical or cultural distance from white medical authority was so great that such subterfuge was unnecessary. Traveling through Georgia in 1899, Wertenbaker kept stumbling upon African American settlements or sections of towns with names like “Hell's Half Acre,” where smallpox had spread for four or five months, sometimes longer, without attracting the least notice from whites. “The disease became epidemic before it was known,” he said.

57

Other books

The Sacred Scroll by Anton Gill

Fated by Sarah Alderson

Goodness Had Nothing to Do With It by Lucy Monroe

Losing Ladd by Dianne Venetta

Playing Along by Rory Samantha Green

The Brat and the Brainiac by Angela Sargenti

Sad Love by MJ Fields

Truth or Dare by Misty Burke

Infection Z (Book 4) by Casey, Ryan

The Clue of the Broken Blade by Franklin W. Dixon