Postwar: A History of Europe Since 1945 (5 page)

Unlike World War One, then, the Second War—Hitler’s War—was a near-universal experience. And it lasted a long time—nearly six years for those countries (Britain, Germany) that were engaged in it from beginning to end. In Czechoslovakia it began earlier still, with the Nazi occupation of the Sudetenland in October 1938. In eastern Europe and the Balkans it did not even end with the defeat of Hitler, since occupation (by the Soviet army) and civil war continued long after the dismemberment of Germany.

Wars of occupation were not unknown in Europe, of course. Far from it. Folk memories of the Thirty Years War in seventeenth-century Germany, during which foreign mercenary armies lived off the land and terrorized the local population, were still preserved three centuries later, in local myths and in fairy tales. Well into the nineteen-thirties Spanish grandmothers were chastening wayward children with the threat of Napoleon. But there was a peculiar intensity to the experience of occupation in World War Two. In part this was because of the distinctive Nazi attitude towards subject populations.

Previous occupying armies—the Swedes in seventeenth-century Germany, the Prussians in France after 1815—lived off the land and assaulted and killed local civilians on an occasional and even random basis. But the peoples who fell under German rule after 1939 were either put to the service of the Reich or else were scheduled for destruction. For Europeans this was a new experience. Overseas, in their colonies, European states had habitually indentured or enslaved indigenous populations for their own benefit. They had not been above the use of torture, mutilation or mass murder to coerce their victims into obedience. But since the eighteenth century these practices were largely unknown among Europeans themselves, at least west of the Bug and Prut rivers.

It was in the Second World War, then, that the full force of the modern European state was mobilized for the first time, for the primary purpose of conquering and exploiting other Europeans. In order to fight and win the war, the British exploited and ransacked their

own

resources: by the end of the war, Great Britain was spending more than half its Gross National Product on the war effort. Nazi Germany, however, fought the war—especially in its latter years—with significant help from the ransacked economies of its victims (much as Napoleon had done after 1805, but with incomparably greater efficiency). Norway, the Netherlands, Belgium, Bohemia-Moravia and, especially, France made significant involuntary contributions to the German war effort. Their mines, factories, farms and railways were directed to servicing German requirements and their populations were obliged to work at German war production: at first in their own countries, later on in Germany itself. In September 1944 there were 7,487,000 foreigners in Germany, most

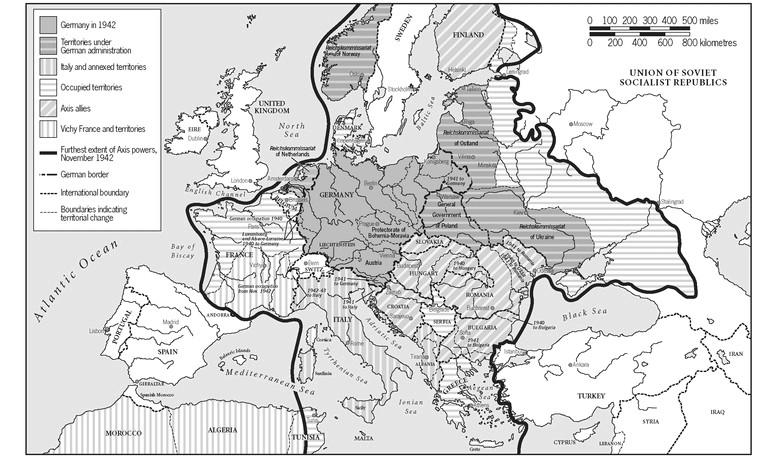

Axis-Occupied Europe: November 1942

of them there against their will, and they constituted 21 percent of the country’s labour force.

The Nazis lived for as long as they could off the wealth of their victims—so successfully in fact that it was not until 1944 that German civilians themselves began to feel the impact of wartime restrictions and shortages. By then, however, the military conflict was closing in on them, first through Allied bombing campaigns, then with the simultaneous advance of Allied armies from east and west. And it was in this final year of the war, during the relatively brief period of active campaigning west of the Soviet Union, that much of the worst physical destruction took place.

From the point of view of contemporaries the war’s impact was measured not in terms of industrial profit and loss, or the net value of national assets in 1945 when compared to 1938, but rather in the visible damage to their immediate environment and their communities. It is with these that we must begin if we are to understand the trauma that lay behind the images of desolation and hopelessness that caught the attention of observers in 1945.

Very few European towns and cities of any size had survived the war unscathed. By informal consent or good fortune the ancient and early-modern centers of a few celebrated European cities—Rome, Venice, Prague, Paris, Oxford—were never targeted. But in the first year of the war German bombers had flattened Rotterdam and gone on to destroy the industrial English city of Coventry. The Wehrmacht obliterated many smaller towns in their invasion routes through Poland and, later, Yugoslavia and the USSR. Whole districts of central London, notably in the poorer quarters around the docklands in the East End, had fallen victim to the Luftwaffe’s

blitzkrieg

in the course of the war.

But the greatest material damage was done by the unprecedented bombing campaigns of the Western Allies in 1944 and 1945, and the relentless advance of the Red Army from Stalingrad to Prague. The French coastal towns of Royan, Le Havre and Caen were eviscerated by the US air force. Hamburg, Cologne, Dusseldorf, Dresden and dozens of other German cities were laid waste by carpet-bombing from British and American planes. In the east, 80 percent of the Byelorussian city of Minsk was destroyed by the end of the war; Kiev in the Ukraine was a smouldering ruin; while the Polish capital Warsaw was systematically torched and dynamited, house by house, street by street, by the retreating German army in the autumn of 1944. When the war in Europe ended—when Berlin fell to the Red Army in May 1945 after taking 40,000 tons of shells in the final fourteen days—much of the German capital was reduced to smoking hillocks of rubble and twisted metal. Seventy-five percent of its buildings were uninhabitable.

Ruined cities were the most obvious—and photogenic—evidence of the devastation, and they came to serve as a universal visual shorthand for the pity of war. Because much of the damage had been done to houses and apartment buildings, and so many people were homeless as a result (an estimated 25 million people in the Soviet Union, a further 20 million in Germany—500,000 of them in Hamburg alone), the rubble-strewn urban landscape was the most immediate reminder of the war that had just ended. But it was not the only one. In Western Europe transport and communications were seriously disrupted: of 12,000 railway locomotives in pre-war France, only 2,800 were in service by the time of the German surrender. Many roads, rail tracks and bridges had been blown up—by the retreating Germans, the advancing Allies or the French Resistance. Two-thirds of the French merchant fleet had been sunk. In 1944-45 alone, France lost 500,000 dwellings.

But the French—like the British, the Belgians, the Dutch (who lost 219,000 hectares of land flooded by the Germans and were reduced by 1945 to 40 percent of their pre-war rail, road and canal transport), the Danes, the Norwegians (who had lost 14 percent of the country’s pre-war capital in the course of the German occupation), and even the Italians—were comparatively fortunate, though they did not know it. The true horrors of war had been experienced further east. The Nazis treated western Europeans with some respect, if only the better to exploit them, and western Europeans returned the compliment by doing relatively little to disrupt or oppose the German war effort. In eastern and south-eastern Europe the occupying Germans were merciless, and not only because local partisans—in Greece, Yugoslavia and Ukraine especially—fought a relentless if hopeless battle against them.

The material consequences in the East of the German occupation, the Soviet advance and the partisan struggles were thus of an altogether different order from the experience of war in the West. In the Soviet Union, 70,000 villages and 1,700 towns were destroyed in the course of the war, along with 32,000 factories and 40,000 miles of rail track. In Greece, two-thirds of the country’s vital merchant marine fleet was lost, one-third of its forests were ruined and a thousand villages were obliterated. Meanwhile the German policy of setting occupation-cost payments according to German military needs rather than the Greek capacity to pay generated hyperinflation.

Yugoslavia lost 25 percent of its vineyards, 50 percent of all livestock, 60 percent of the country’s roads, 75 percent of all its ploughs and railway bridges, one in five of its pre-war dwellings and a third of its limited industrial wealth—along with 10 percent of its pre-war population. In Poland three-quarters of standard gauge rail tracks were unusable and one farm in six was out of operation. Most of the country’s towns and cities could barely function (though only Warsaw was totally destroyed).

But even these figures, dramatic as they are, convey just a part of the picture: the grim physical background. Yet the material damage suffered by Europeans in the course of the war, terrible though it had been, was insignificant when set against the human losses. It is estimated that about thirty-six and a half million Europeans died between 1939 and 1945 from war-related causes (equivalent to the

total

population of France at the outbreak of war)—a number that does not include deaths from natural causes in those years, nor any estimate of the numbers of children not conceived or born then or later because of the war.

The overall death toll is staggering (the figures given here do not include Japanese, US or other non-European dead). It dwarfs the mortality figures for the Great War of 1914-18, obscene as those were. No other conflict in recorded history killed so many people in so short a time. But what is most striking of all is the number of non-combatant civilians among the dead: at least 19 million, or more than half. The numbers of civilian dead exceeded military losses in the USSR, Hungary, Poland, Yugoslavia, Greece, France, the Netherlands, Belgium and Norway. Only in the UK and Germany did military losses significantly outnumber civilian ones.

Estimates of civilian losses on the territory of the Soviet Union vary greatly, though the likeliest figure is in excess of 16 million people (roughly double the number of Soviet military losses, of whom 78,000 fell in the battle for Berlin alone). Civilian deaths on the territory of pre-war Poland approached 5 million; in Yugoslavia 1.4 million; in Greece 430,000; in France 350,000; in Hungary 270,000; in the Netherlands 204,000; in Romania 200,000. Among these, and especially prominent in the Polish, Dutch and Hungarian figures, were some 5.7 million Jews, to whom should be added 221,000 gypsies (Roma).

The causes of death among civilians included mass extermination, in death camps and killing fields from Odessa to the Baltic; disease, malnutrition and starvation (induced and otherwise); the shooting and burning of hostages—by the Wehrmacht, the Red Army and partisans of all kinds; reprisals against civilians; the effects of bombing, shelling and infantry battles in fields and cities, on the eastern Front throughout the war and in the West from the Normandy landings of June 1944 until the defeat of Hitler the following May; the deliberate strafing of refugee columns and the working to death of slave labourers in war industries and prison camps.

The greatest

military

losses were incurred by the Soviet Union, which is thought to have lost 8.6 million men and women under arms; Germany, with 4 million casualties; Italy, which lost 400,000 soldiers, sailors and airmen; and Romania, some 300,000 of whose military were killed, mostly fighting with the Axis armies on the Russian front. In proportion to their populations, however, the Austrians, Hungarians, Albanians and Yugoslavs suffered the greatest military losses. Taking all deaths—civilian and military alike—into account, Poland, Yugoslavia, the USSR and Greece were the worst affected. Poland lost about one in five of her pre-war population, including a far higher percentage of the educated population, deliberately targeted for destruction by the Nazis.

2

Yugoslavia lost one person in eight of the country’s pre-war population, the USSR one in 11, Greece one in 14. To point up the contrast, Germany suffered a rate of loss of 1/15; France 1/77; Britain 1/125.

The Soviet losses in particular include prisoners of war. The Germans captured some 5.5 million Soviet soldiers in the course of the war, three quarters of them in the first seven months following the attack on the USSR in June 1941. Of these, 3.3 million died from starvation, exposure and mistreatment in German camps—more Russians died in German prisoner-of-war camps in the years 1941-45 than in all of World War One. Of the 750,000 Soviet soldiers captured when the Germans took Kiev in September 1941, just 22,000 lived to see Germany defeated. The Soviets in their turn took 3.5 million prisoners of war (German, Austrian, Romanian and Hungarian for the most part); most of them returned home after the war.

In view of these figures, it is hardly surprising that post-war Europe, especially central and eastern Europe, suffered an acute shortage of men. In the Soviet Union the number of women exceeded men by 20 million, an imbalance that would take more than a generation to correct. The Soviet rural economy now depended heavily on women for labour of every kind: not only were there no men, there were almost no horses. In Yugoslavia—thanks to German reprisal actions in which all males over 15 were shot—there were many villages with no adult men left at all. In Germany itself, two out of every three men born in 1918 did not survive Hitler’s war: in one community for which we have detailed figures—the Berlin suburb of Treptow—in February 1946, among adults aged 19-21 there were just 181 men for 1,105 women.