Postcards (26 page)

Authors: Annie Proulx

Often at night, when the heavens are bright, thought Loyal, but he was hearing.

‘Look into the sky and you are looking into time and nothing that you see is now – it is all so remote and ancient that the human mind quails and shrinks as it approaches. Listen, extinction is the fate of all species, including ours. But before we go maybe we’ll get a quick look at a blinding light. I have felt – I have felt —’ and he stopped. The thrilling voice closed in on itself, became a whisper.

‘And tell you something else. There’s something haywire about you. There’s something truly fucked up about you. I don’t know what it is, but I can smell it. You’re accident-prone. You suffer losses. You’re tilted way far off center. You run hard but don’t get anywhere. And I don’t think it’s easy for you.’ He looked at Loyal. The old black eyes looked at Loyal. Tiny yellow rectangles, reflections of the open door, invited him to step through. Loyal took a breath, exhaled. Started to speak, stopped. Began.

‘I can stand it,’ he mumbled, ‘I’m not doin’ so bad. I got some money saved up. What the hell do you expect?’

They sat in darkness, the thick apricot light firing strewn distant rocks.

‘Some other time,’ said Ben. ‘Here, have another shot of the misery water.’

The wind blew itself out. The morning sky was blue glass, the lodgepole points touched the hard surface. If he threw a rock it would smash, if he breathed his whiskey-fumed breath at it, it would melt.

An eagle turned a great circle under the dome. A strip of meadowlark’s call. He urinated on a prickly pear cactus. The sky reeled. He saw the bright points of his water, the sparkle of bottle-glass, Ben weaving beside him, face caved in as from a blow. His dental plate on the table.

‘No women,’ said Loyal, ‘I can’t be around women.’

Ben said nothing, one foot crushing a tuft of fleabane. The poisonous water jerked from his scarred bladder. His blind, drunk eyes saw through the glass sky, saw the black chaos behind the mocking brightness.

‘There’s something. I choke – like a kind of bad asthma – if I get around them too close. If I get interested in them. You know. Because of something that happened long ago. Something I did.’ The broken glass was everywhere. He saw blades and leaves of glass, the round brittle stems of red glass, insects as dying drops of molten glass hardening in the solid air, the gravel under his feet rough glass. He was barefoot. He could see the crust between his toes, the slackening skin on his forearms, toenails distorted by cheap boots.

‘I see the way you throw yourself at trouble. Punish yourself with work. How you don’t get anywhere except to a different place. I recognize a member of the club. I don’t imagine you’d try a head doctor.’

Talking crap. He should have guessed Ben’s larynx had been shredded by the glass he’d eaten the night before. He could feel it sawing in his own throat and lungs. Christ, his throat felt full of blood. ‘No. Don’t believe in it. Life cripples us up in different ways but it gets everybody. It gets everybody is how I look at it. Gets you again and again and one day it wins.’

‘Oh yes? And the way you see it you just have to keep getting up until you can’t get up? Question of how long you can last?’

‘Something like that.’

Ben laughed until he retched.

FROM THE PICTURE WINDOW in front of the table in her trailer Jewell looked out over the mobile home park below. If she pulled back the blue-flowered curtain in the bathroom window she could see the old house, down on its knees now. The roof had broken under a freight of snow the winter before. Ott wanted to burn it up, called it an eyesore that made the trailer park look bad, hanging over the pastel tubes like a wooden cliff, but she couldn’t let go of the place, still limped in back of it every day in the summer to keep the old garden patches going, though the woodchucks and deer moved in with the weeds and did a lot of damage. Her ankles swelled so. It wants to go wild again, she thought.

‘I worked on getting them gardens up the way I like for most of my grown-up life and I am not about to turn them over to the wildlife. What it needs is some boy to set a few traps around the fence. I asked that big fat woman, Maria Swett, down at the trailer park if she knew any boys that was trapping, but she said no. I guess they don’t trap now. Loyal and Ronnie always used to run traps, even when they was little. Loyal made quite a bit of money with the furs. Another thing I could use there is a couple loads of good rotted chicken or cow manure. Gardens need some manure, but try to get Ott to remember to bring any over. Nobody around here keeps cows or chickens any more.’

Her gardens were smaller. She still grew tomatoes and beets, and other garden truck, but not potatoes or com.

‘Too easy to buy it. I get all I need of corn if I buy a bushel, put up some succotash, creamed corn for corn chowder. If Ray and Mernelle come over they’ll bring a dozen fresh ears from some roadside stand. There’s some kids from New Jersey moved into the old Perish place and they been growing Silver Queen the last few years. If they don’t split up, like I heard could happen, and if we don’t get a cool summer, I can keep on buying it from them.’

She hauled some vegetables down to the canning factory where they let her put them up with the commercial loads. Ray and one of the men at the lumberyard brought her a freezer and set it in the extra room, the second bedroom, that she never used but kept in case Loyal came home. She tried it for two years, but didn’t like the taste of the vegetables along in March when they were full of ice crystals. She went back to canning then, and because there was no cellar or pantry, she stored the jars in the unplugged freezer. But bought her beef and chicken at the IGA and complained they had no flavor.

‘Mernelle, you remember the hens we raised were so good. I can just taste one of those big roasters, go seven or eight pounds, sitting on the platter all crispy and roasted with a good bread stuffing. Make your mouth water just to smell it. I always liked my food and I guess I miss the stuff we grew on the farm. Take the beef. Your dad used to keep out two steers each year for beef. We’d have two big butchering days, one in October, one in early December, right through the depression when a lot of people went hungry, and I’d put up

beef. Can it. Make stewed beef sometimes and can it. There’s nothing so tender and good as home-canned beef. You can’t buy it for love nor money. There’s nothing else tastes like it. Deer meat, too. That’s the way we always used to do the deer meat. Loyal and Dub and dad used to keep us in deer. Now people, flatlanders, they get a deer, what do they do with it? They cut it up into “venison” roasts and steaks and complain because it’s tough or too much tallow. They put it in the freezer. Toughens it up, I’d say. The way we used to do, it was always as tender as custard and you could skim off the tallow just by letting it set in a cool place before you put it up.’

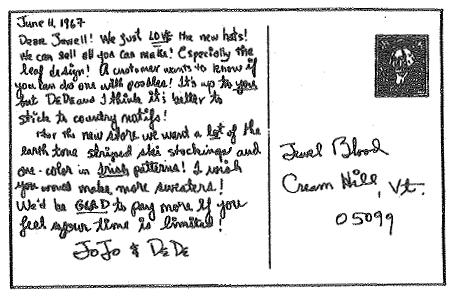

The trailer, with its cunning spaces and cupboards pleased her. But sometimes she thought of the old kitchen, seven steps from the sink to the table, back and forth all day. It was Ray’s idea, that she ought to have a trailer with a little oil heater and plumbing and electric instead of trying to heat the old house with the wind sifting through, struggling to carry in wood. It was like being on a visit to wake up in the morning in the narrow bed with the flowery sheets and see the sunlight like a handful of yellow rulers coming through the Venetian blinds instead of the torn shade with its crooked mends and pinpoint stars. The plaid sofa had shiny arms and a matching chair on a swivel, a comfortable thing to lean back in. The chair faced the television set Ray and Mernelle had bought her and she turned it on while she cooked in the kitchen or knitted, just for the company, though the tinned quality of the voices never let you forget they were not real people. She enjoyed the little stainless steel sink in the kitchen, the smart refrigerator with its ice cube trays that she never pulled out unless Mernelle and Ray were visiting, ‘not being in the habit of ice,’ she said. Loyal’s postcards with the bears were in a cigar box in the cupboard. Once in a while one still came. The smell of the trailer was the only drawback. In the old house she had never noticed smells unless something were burning or Mernelle brought in a big bouquet of lilacs, but here there was a headachey smell like the stuff they used to stick down floor tiles. Ray said he thought it was the insulation.

‘Whatever it is, it’ll wear off one of these days. What can’t be cured must be endured.’ She could always go outside and get a breath of air.

Three days a week she drove over to the canning factory and worked

in the cutting-up room. Extra days if there was a rush order. They’d gone over to automatic sheers with adjustable settings and blades, and she’d learned the new machines faster than anyone else. The forelady, Janet Cumple, had marveled.

‘Look how good Jewell’s caught on,’ she said in front of the others. Jewell couldn’t think how long it had been since someone said a word of praise to her. She’d gone red and trembly when they all looked at her, thought of Marvin, the dead brother, telling her she was a smart little kid because she’d found his homemade baseball, hide stitched over a knob of rubber bands, in the long grass after he’d given up. She couldn’t have been older than four.

The rest of the time she put into the garden, into knitting hats and sweaters for the ski shop, into driving around.

‘Problem is, they want me to use that plain old wool, it’s not even spun smooth, you’ll find burrs and hayseed in it, instead of the pretty colors you can get down at the Ben Franklin. I’ll go along with using the wool instead of the acrylic, the acrylic don’t have the bounce and it sags, but I don’t see a thing wrong with a little color. All that grey and brown and black it gets dull to work on a piece. So I let off steam with Ray’s sweaters.’ Dub down in Miami didn’t want to see wool. He sent photographs of himself playing golf in shorts and a flowery shirt. His artificial arm seemed very real, except the color was a pinker color than his tanned right arm. But every year for Christmas she gave Ray a patterned sweater in staggering colors and designs, jagged yellow bolts encircling his torso, red airplanes swooping across a cobalt-blue breast, endless green reindeer marching over maroon and orange sleeves. He tried them on, praising them and exclaiming over the fine details while Mernelle covered her eyes and moaned, ‘No, oh no, I can’t stand it.’

The duck sweater. She had been driving along the lake, eighty miles west of home on one of her excursions, and on a windy October day chanced on a church sale in an ugly strung-out village. Two women wrestled with a school easel, one tying posters to it with string, the other piling stones around the easel legs to keep it upright in the wind.

‘BAKE & RUMMAGE & WHITE ELEPHANT SALE

. Benefit Mottford Congregational Church.’ There was a good place to park just beyond the sign.

The baked goods were not the same as they used to be. Instead of brownies, square chocolate cake still in the pan, apple pies, oatmeal cookies and home-baked bread, there were cake-mix things with three times as much frosting as anybody needed, cocktail snacks made out of cereal and nuts. The rummage tables had the same worn kitchen tools, statues of slave girls with glitter on them, wooden boxes and peg racks. The needlework seemed to be all teacloths with embroidered windmills, never used, laid away in some mothball trunk since the twenties, pale yellow crocheted bedspreads with the texture of barbwire and baby bibs stained with ancient applesauce. The babies had to be grown men and women now.

A big square wicker basket with a lid. That caught her attention. The basket came up to her waist, and she lifted the lid and looked in. It was packed with yarns, hundreds of colors and weights, fine hand-spun linen thread, hand-dyed skeins of wools, the dark green of cocklebur, red madder root, indigo blue, the cloudy gray of walnut, gold knotweed. Richer, more subtle colors than she’d ever used. The deeper she rummaged the more treasures she found, a tender color that made her think of teal-wing ducks, and in that minute she saw the sweater, saw it entire with the ducks in many colors swimming against a dark background, and every few stitches she’d work in cattails behind the ducks.

‘That was old Mrs. Twiss’s yarns, she died in jury and the fam’ly wants to clear all the stuff out of the house,’ the woman blurted. She was lantern-jawed and with an anxious voice like prayers. ‘Half the reason we’re havin’ this sale is to sell off her stuff. They kept the sheep until Mr. Twiss died, and then she still had a lot of wool on hand. She made rugs on a loom. I never cared for them myself – I like a nice nylon carpet in a solid color – but I guess a lot of people, the summer people, bought them. She knitted, too. This basket was her knitting yarns.’

‘What are you asking?’ Jewell wanted that basket as bad as she’d ever wanted anything.

‘Five dollars sound about right? It’s mostly a lot of leftovers. Prob’ly be all right for socks or something.’

It took four of them to carry the basket out to her car, and then the lid of the trunk wouldn’t close and she had to tie it down with

string borrowed from the poster-tying woman. She took her name and address and mailed the string back the next day with thanks.