Poseur

Text copyright © 2008 by Rachel Maude

Illustrations copyright © 2008 by Rachel Maude and Compai

All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced,

distributed, or

transmitted in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without the prior written permission

of the publisher.

Poppy

Little, Brown and Company

Hachette Book Group USA

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our Web site at

www.pickapoppy.com

First eBook Edition: January 2008

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental

and not intended by the author.

ISBN-13: 978-0-316-02927-8

Contents

The Girl: Blanca (last name unknown)

The Girls: Melissa Moon, Charlotte Beverwil, Petra Greene, Janie Farrish

The Girl: Gretchen Sweet (aka “Naomi”)

For my parents

Melissa Flashman, tough-talking agent, fashionable friend: thank you for making it all happen. Cindy Eagan, editor extraordinaire:

many thanks for your incisive feedback and conscientious advice, your humor, your cracking whip. To the lovely ladies of Compai:

I am in awe. Jamie Mae Lawrence: without you, I never would have survived high school. And by high school, I mean, like .

. .

life

. Ben Nugent: I will forever cherish our Chango days. I acknowledgeth thee. Annie Baker, kasha to my pickle, sponge to my

bone, willow to my shrub, orangutan to my feral cat: you are the love of my life, and for that I am deeply resentful. Jess:

Que’est-ce que c’est un gallumpher? You were my first idol, and I love you. Gabe: you scream into toy cell phones and throw

them against walls. You snort horseradish at Canter’s. You’re like a brother to me, man. And I love you. Mom: you are the

smartest, wisest, wittiest person I know. Thank you for showing me how to be a good person. And for telling my kindergarten

teacher I did not have a learning disability. I love you. Dad: you took me to see

The Little Mermaid

. You bought me Doc Martens when they were cool. You made me steak and eggs the night before the S.A.T. Thank you for being

present every day of my life. I love you.

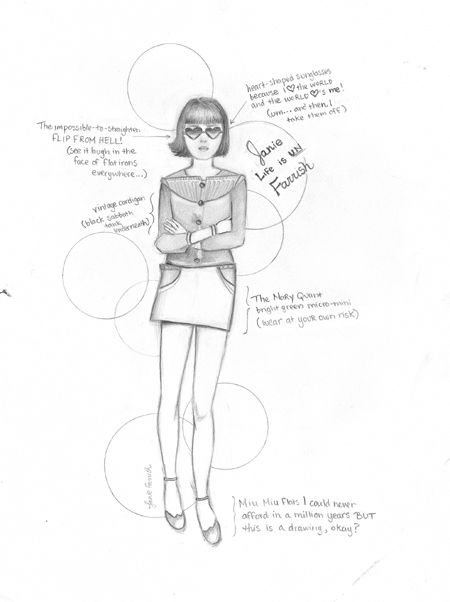

The Girl: Janie Farrish

The Getup: Cream cashmere cardigan, vintage Black Sabbath t-shirt rags tank, yellow silk Miss Sixty flats, silver bangles,

and it

It

was still there when she woke up, hanging neatly on the back of her closet door.

It

was still the same bright green — like a new leaf, like a traffic light set to go.

It

was the most spectacular thing she owned, and if some other sixteen-year-old girl had owned it, it would have been the most

spectacular thing she owned too.

But some other sixteen-year-old girl didn’t own it. Janie did.

She’d found it at one of Jet Rag’s legendary dollar sales, forever sealing Janie’s opinion that Jet Rag was, and always will

be, the best vintage clothing store in the universe. Not that she’d been to every vintage clothing store in the universe.

She didn’t have to. Jet Rag was right there on La Brea Boulevard, a mere twenty minutes away from her house on the other side

of the hills, and a mere minute away from the La Brea Tar Pits. All of L.A. is divided by those who cruise La Brea for the

tar pits and those who cruise La Brea for Jet Rag. If you go for Jet Rag, chances are you’re sixteen, beautiful, and impossibly

unique. If you go for the tar pits, chances are you’re six or sixty or really, really lame. (So there’s a black swamp in the

middle of Los Angeles that burps up dinosaur bones. You can’t

wear

dinosaur bones. And if you can’t wear something, what’s the point?)

Every Saturday morning, the Jet Rag staff dumps an enormous load of clothes in the middle of their cracked-asphalt parking

lot and people seriously riot over them like those peasants in the French Revolution. Every piece of clothing costs exactly

one dollar. Depending on what you find, a dollar ranges from

incredible deal

to

insane rip-off.

And since the deal-to-rip-off ratio is like a hundred to one, the rioting makes perfect sense. Everyone there wants to find

it

first.

Par example:

Janie’s best friend, Amelia Hernandez, found a mint condition, vintage wool houndstooth Yves Saint Laurent jacket. YSL jacket

+ $1.00 = incredible deal. On the flip side, Janie found a “Pinky and the Brain” t-shirt with bloodstains on it: Pinky and

the Brain + bloodstains + $1.00 = insane rip-off. Janie was so grossed out, she actually puked up some of the orange juice

she’d had for breakfast. Which meant the next person to pick up the shirt would have blood

and

barf to contend with.

But the Jet Rag dollar-sale isn’t for the faint of heart. The Jet Rag dollar sale is for die-hard, hard-core fashionistas:

the hippest of the hip, the slickest of the slick, the sickest of the sick.

Well, and homeless people.

That summer Amelia seemed to have all the luck. In addition to the Yves Saint Laurent jacket, she found a sexy little Western

shirt with mother-of-pearl buttons, a pair of blue suede kitten-heeled boots, and — the crème de la nonfat creamer — a vintage

Sonic Youth “Goo” t-shirt that Janie had a sinking feeling was from the original nineties tour. Not that she wasn’t happy

for Amelia. (She was even happier when the t-shirt turned out to be eighteen sizes too big for either one of them to actually

wear.)

By the end of August, Janie still hadn’t found anything. She was just about to surrender, to throw her empty-handed hands

in the air, when she spotted

it.

It

— to be specific — was a vintage green cotton miniskirt by none other than Mary Quant, the number one designer for such sixties

fashion icons as Mia Farrow and the British supermodel Twiggy. Janie was beginning to think she looked like a sixties fashion

icon. Maybe that sounds egotistical; it’s not. It’s not like guys fantasize about Twiggy, even if they do know who she is,

which of course they don’t. Why would they? In her heyday, Twiggy looked like a cross between an alien and an eleven-year-old

boy. Seriously, who’d want to take the shirt off of that? No self-respecting guy at Winston Prep, that’s for sure.

Janie knew firsthand.

She had always gotten straight As, and now, as she was beginning to discover, her grade average also applied to her bra size.

Janie’s boobs, if you could dignify them with that term, were the great tragedy of her life. They were absolute traitors to

the cause. Not that the cause was such a big deal — just her happiness, her dreams, her very will to live.

If it hadn’t been for her legs, she might have been forced to do something drastic. Her legs — long and smooth and track team–toned

— were her saving grace. Who cared if her bra looked like a pair of eye patches? She could pull off a miniskirt like nobody’s

business. Which was why she was so happy to find it. That is, until she went home and tried it on.

Then she was ecstatic.

Janie felt like the kind of girl who zipped around London in an Aston Martin with Jude Law. The kind of girl who inspired

older Italian men with cultivated taste to tip their hats in appreciation. The kind of girl who knotted silk scarves under

her chin and hailed cabs in New York City while enchanted tourists snapped pictures ( just in case she was famous).

She felt like the kind of girl she wasn’t.

It’d be one thing if girls like this didn’t exist (Janie could just tell herself she was holding herself up to some impossible

standard), but girls like this did exist. And what was worse, she went to high school with them.

That bit about Italian men? Actually happened to Petra Greene. The New York City cab story? Straight from the life of Melissa

Moon. And London? The Aston Martin? With Jude without-a-flaw Law? Just another blip in Charlotte Beverwil’s everyday existence.

But we’ll get to them later.

This year would be different. This year Janie would show up at school wearing

it.

And

it

would redefine her, force all of Winston to pause and reevaluate their previous misconceived notions.

It

would banish forever their memory of her as an entering freshman; in a world of double 66 Gucci totes and monogrammed Kate

Spade organizers, Janie had arrived sporting an ink-stained Everest backpack. In a world of eyebrows tended to biweekly by

professional “browticians,” Janie had arrived with two self-plucked “tadpoles” on her face (or so she was informed by the

appalled Charlotte Beverwil). In a world of flawless complexions, Janie had arrived with a spackle of zits on her cheeks,

chin, and chest. At Winston Prep, acne was widely perceived as a

historical

malady, like smallpox or polio. No one actually

got

those things anymore . . . did they? Janie’s new, elite peers eyed her with suspicion, like she’d just rolled in from some

contaminated Third World country.

It was the acne that did her in. At the end of ninth grade, Janie Farrish’s chin ranked number two on the Winston yearbook’s

“don’t” list. (Tommy Balinger — who streaked the Winston vs. Sacred Heart girls’ badminton championship wearing nothing but

two shuttlecocks on his nipples — made number one.)

But today was the first day of tenth grade, a whole new beginning. Janie’s eyebrows were smooth and arched, her ink-stained

backpack long disposed of. Best of all, her complexion was perfect: clear and fresh and sun-kissed. For the first time in

years, Janie could see her actual face: her neat, strong nose and defined jaw line, her extra-high cheekbones. Her upper lip,

fuller than her lower lip, perpetually pouted. And her enormous gray eyes, shadowy with lashes, looked soft and shy. Sometimes

— when the sun was shining and she’d had a good amount of sleep, when sweet songs played in her head and her bangs fell the

right way, when the sky rose like a peaceful blue parachute and the world was on her side — Janie realized she was pretty.

But the feeling was so fragile and new, the slightest setback made it disappear. The sun ducked behind a cloud, her bangs

flipped the wrong way — and that was it. She felt ugly again. Which feeling was the right one? She honestly couldn’t tell.

Janie plucked her new green skirt from the plastic hanger. She pulled it past her trim knees, shimmied it up around her thighs,

lined up the seams, and zipped. Her “new” rags tank (she’d scissored the sleeves off her Black Sabbath t-shirt the night before)

slipped down her right shoulder, exposing a bright turquoise bra strap. She turned to face the mirror, greeting herself with

her best self-assured smile.

She was ready.

Even though he woke up forty-five minutes late, Jake Farrish was already dressed and eating breakfast before his twin sister.

Jake didn’t waste too much time constructing his look, if that’s what you chose to call it. His mom preferred to call it his

“look away.”

Not that her opinion mattered.

Jake pretty much wore old cords, faded seventies cowboy shirts, black Converse, and his gray United States of Apparel hoody

with the Amnesiac pin every day. His hair he rewarded with his greatest investment of time — a whole five and a half minutes.

(Who knew the distribution of one dime-sized blob of wax required so much attention?) When he was done, he inspected himself

from all angles, furrowing his brow like James Dean. Not that Jake looked like James Dean. With his mussed black-brown hair,

porcelain skin, and flushed cheeks (interrupted only by a trilogy of beauty marks), Jake resembled a brown-eyed Adam Brody.

Of course, Jake

hated

that comparison.

“I do

not

look like that guy!” he’d insist every time his sister put in the Season One DVD of the tragically canceled

O.C.

“Don’t look at me,” came Janie’s reply. “

I

think you look like Summer.”

The Farrish kitchen was small and square, and the appliances old and broken-down. Not that their mother used those words.

Mrs. Farrish preferred the term “temperamental,” as in “temperamental appliances require special treatment.” Jake and Janie

were warned to be “gentle” with the dishwasher, “careful” with the microwave, and “mindful” of the freezer door. If Mrs. Farrish

had her way, the twins would tip-toe around the kitchen like it was a mental ward. She acted as if slamming the refrigerator

door would drive the toaster to suicide.

By the time Janie entered the kitchen, Jake was well into his second bowl of Cheetah Chomps. “Hey,” she said, staring into

the fridge and doing her best to look casual. She could feel her brother assessing her outfit the way overprotective brothers

sometimes do. Jake was fundamentally hypocritical when it came to female fashion. The equation went something like this:

Girl + Miniskirt = Smokin’

Girl + Shared Genetic Material + Miniskirt = Repulsive

She opened the fridge, letting her straight brown hair fall like a curtain across her face. Janie would not look away from

the fridge until Jake said something. She sort of hoped he’d tell her she looked like a slut. Then she could just toss her

hair back, arch one cool eyebrow, and thank him for the compliment.

“Dude,” he began at last, “did you know cheetahs can achieve speeds of up to seventy miles per hour?”

Janie slammed the fridge shut. What kind of guy reads the back of a cereal box while his sister, his own

flesh and blood,

was tricked out like a wanton whore?

“Wow, Jake,” she scowled. “What an amazing and fun fact.”

“Whoa . . . ,” he continued, hunching over his cereal like a caveman. “One of its natural predators is the eagle. How awesome

is that? Like the eagle’s all . . .

bwa

! And the cheetah’s all, I don’t

think

so!”

With that, he unleashed a mighty eagle-cry and karate-chopped the air for a full fifteen seconds. Janie watched him, doing

her best not to crack a smile. She folded her arms and asked the inevitable.

“Um . . . are you retarded?”

“Yes,” he replied. He scooted his chair back and pointed at his sister with his spoon. “What are you doing dressed like that?

You look like a skanky-ass ho.”

“Come on” — she grinned, tossing him the car keys — “we’re gonna be late.”