Poison (50 page)

Authors: Jon Wells

CHAPTER 28

LIVING VICTIMS

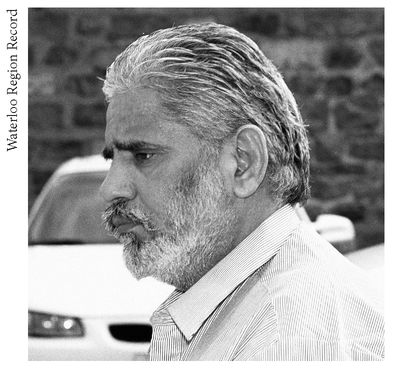

It was two days before Christmas 2002, at Barton Street jail in Hamilton. Sukhwinder Dhillon sat behind the glass partition in the visitors’ area, took the phone receiver in his hand. In 30 days the convicted double murderer would be moved east to Millhaven Federal Penitentiary near Kingston. He had filed appeals on both convictions. Russell Silverstein had declined to continue as his lawyer. The appeals, as well as all of Dhillon’s court costs for more than five years, would be paid for by legal aid. A journalist sat on the other side of the glass accompanied by a Punjabi interpreter. In Punjabi, Dhillon said he would not speak to the reporter. “I’m appealing,” he said. “I won’t talk without my lawyer.”

In his orange prisoner’s jumpsuit and laceless sneakers, Dhillon looked smaller, rounder than in the suit he had worn in court. His hair and beard were even whiter now. He had continued to soften in jail.

“Tell Dhillon it’s over,” the journalist pressed, through the interpreter. “Tell him it’s over, he was convicted, and now is his chance to give his side of the story.”

“No,” Dhillon replied, shaking his head. “It’s under appeal. I won’t talk.”

“Ask him how he feels.”

“I don’t belong here. I’m innocent.”

Dhillon hung up the receiver, stood, and walked back to his life behind bars.

In Dhillon’s mind, he clung to the hope of getting off on appeal, or early parole. He had never confessed. And if he got out, what would he do for cash? The money he had from Parvesh’s death was all but gone, and he never collected any money from Ranjit’s life insurance. No one would ever get that money. The claim was void. But there might be other ways. Maybe he’d have the money from the lawsuit by the time he got out.

Lawsuit? In 1999, while Dhillon was in jail waiting for his trial to begin, he filed the lawsuit. It was over a slip and fall he claimed he suffered in a Hamilton apartment building lobby in April 1997. The statement of claim papers had been delivered to

the head office of a building management company in St. Catharines. Dhillon claimed the lobby floor had been wet and slippery. The papers said that Sukhwinder Dhillon, the plaintiff, sought special damages from the fall of $200,000, plus $50,000 for pre-and post-judgment interest, and costs of his action. Co-plaintiff Gobind Dhillon, his mother, sought $25,000 plus “GST on costs.” His daughters, the papers said, represented by their now-official guardian, Dhillon’s niece Sarvjit, each claimed $25,000 and Sarvjit herself claimed $25,000.

the head office of a building management company in St. Catharines. Dhillon claimed the lobby floor had been wet and slippery. The papers said that Sukhwinder Dhillon, the plaintiff, sought special damages from the fall of $200,000, plus $50,000 for pre-and post-judgment interest, and costs of his action. Co-plaintiff Gobind Dhillon, his mother, sought $25,000 plus “GST on costs.” His daughters, the papers said, represented by their now-official guardian, Dhillon’s niece Sarvjit, each claimed $25,000 and Sarvjit herself claimed $25,000.

The claim said that since the fall Dhillon’s “enjoyment of life and basic amenities have been severely curtailed … he is unable to climb stairs. The plaintiff is in pain and taking medication, is unable to engage in social and recreational activities to which he was accustomed, and unable to carry gainful employment. [It has] caused inconvenience and discomfort, he is unable to do normal household chores to which he had been responsible.” The injuries “caused great pain and shock to the plaintiff.” As for the kids and Gobind, they had “sustained a lack of guidance and care and companionship that the plaintiffs might reasonably have expected from Sukhwinder Dhillon, if he had not been injured.”

Dhillon filed a lawsuit while in prison.

Guidance, care, and companionship

.

.

In February 2003, six years after the “fall,” Dhillon sat in his Millhaven cell serving a life sentence. The injury claim, according to a lawyer he hired in Hamilton, was “firmly open.” There’s a big “if,” but if the claim ever goes before a judge and Dhillon is awarded damages, the money would be payable in

due course. Prisoners have the right to vote. And win lawsuits. The lawyer said where the claim goes from here is up to his client. A nice deal, lawsuits.

due course. Prisoners have the right to vote. And win lawsuits. The lawyer said where the claim goes from here is up to his client. A nice deal, lawsuits.

Dhillon had been convicted twice, but there were still so many loose ends to the story. Kushpreet. The twins. Warren Korol would always be certain Dhillon killed them all. But Dhillon would never answer for those deaths. No charges were ever laid in India. It left Korol with an empty feeling. And then there was the third brother. Korol had found out about Darshan late in his investigation. But there was never enough evidence to consider entering it before the court. But it was there in Korol’s investigation notebook.

Aug. 19, 1997

That was the date he typed, summarizing notes he made in a conversation with Sarvjit, Dhillon’s 22-year-old niece. One day Sarvjit had paged Korol. She wanted to talk about her late father, Darshan. She told him events that happened one day back in January 1992, in Ludhiana. Korol wrote:

Sarvjit Kaur Dhillon told me that her father had died a short time ago while in India but there was no post-mortem done.

Sarvjit said that she had been there when her father died. The kids were told it was a heart attack. It did not seem like a heart attack. She was 17 at the time. As Darshan passed away, she saw recognition in his eyes for her. He clutched at his throat, tried to say something to her, but couldn’t. His teeth were clenched tight together. There it is again, thought Korol. The death grin.

Sarvjit told me that her father cried and his body was rigid. She told me that her father became ill after he drank something. Sarvjit told me that Sukhwinder Singh Dhillon was in India at the time of Darshan’s death. Sarvjit said she was disturbed that Sukhwinder

Singh Dhillon did not mourn his brother’s death, he was not acting like a person who lost his brother, and he was drinking a lot.

Singh Dhillon did not mourn his brother’s death, he was not acting like a person who lost his brother, and he was drinking a lot.

Dhillon was there for the mourning that followed Darshan’s sudden death, there for the reading of the

Kirtan Sohila

, sprinkling of the ashes in the sacred river. He stayed three months. Dhillon had watched Sarvjit, tears filling her eyes. He walked over to her. Don’t cry, Dhillon said. Don’t be sad. Your father was once a police officer. He surely had many enemies.

Kirtan Sohila

, sprinkling of the ashes in the sacred river. He stayed three months. Dhillon had watched Sarvjit, tears filling her eyes. He walked over to her. Don’t cry, Dhillon said. Don’t be sad. Your father was once a police officer. He surely had many enemies.

Sarvjit Kaur Dhillon told me that Sukhwinder Singh Dhillon suggested that maybe someone poisoned her father.

There were the dead in Dhillon’s wake. There were also his living victims. The best that could be said about the fate of Dhillon’s second wife, Sarabjit Kaur Brar, was that she lived to tell about the nightmare. But she carried a wound that would never heal—the loss of her babies. She thought about them every day, tried to remember the few healthy living days they had enjoyed before dying in her arms. Sarabjit could not even contemplate the hope that the boys’ souls were with God. They had been too young, they had no souls. It brought tears to her eyes. As for the babies, the remains of Gurmeet and Gurwinder were buried again in accordance with Sarabjit’s wishes.

Sarabjit found out about the guilty verdict in Parvesh’s murder a couple of days after the fact in the late summer of 2001. She had awakened, alone, and seen the Punjabi-language newspaper on the kitchen table. Her brother had left it for her. No note, just open to a headline. Guilty. Jodha was found guilty. Sent to jail for life. He was getting the punishment he deserved. Her eyes lit up and she smiled. And she said it, quietly, but firmly. “

Hungi!

” Yes! It felt sweet. She read the news at her home—near Brampton, Ontario. In the days following the first Dhillon trial, she had filed papers claiming refugee status in Canada for herself and her parents. Through Dhillon, in a twisted way, she had indeed made it to Canada, and had a shot at staying.

Hungi!

” Yes! It felt sweet. She read the news at her home—near Brampton, Ontario. In the days following the first Dhillon trial, she had filed papers claiming refugee status in Canada for herself and her parents. Through Dhillon, in a twisted way, she had indeed made it to Canada, and had a shot at staying.

Sarabjit found her life in Canada was not the paradise she had once imagined. She slept on a mattress on the floor of a basement her family rented, worked at the airport packing in-flight meals, while her parents toiled at a mushroom farm. She liked the summers, a nice change from the scorching Indian heat, but she hated the hard, gray winters, when the air seemed to rake your face. When she was a little girl, Sarabjit had talked about it with her friends.

Cane-a-da

. Land of beauty, wealth. She thought Canada would be everything, and in fact for her it was nothing. Everything is work, work, work. Up in the morning, home at night. Start all over again. Did she want to return home? No. In Panj Grain she would never be able to marry again, not after being divorced and having children. But here, in Canada, a more liberal culture, they don’t care about that. For Sarabjit, that was the only saving grace of the Canadian dream.

Cane-a-da

. Land of beauty, wealth. She thought Canada would be everything, and in fact for her it was nothing. Everything is work, work, work. Up in the morning, home at night. Start all over again. Did she want to return home? No. In Panj Grain she would never be able to marry again, not after being divorced and having children. But here, in Canada, a more liberal culture, they don’t care about that. For Sarabjit, that was the only saving grace of the Canadian dream.

As time wore on, Sarabjit earned more money, picked up a few more words of English. Her face, a sullen mask months before, seemed brighter, prone to break into easy smiles. She acquired a new confidence, could look men in the eye when she spoke to them, just like a Western woman does. She missed home terribly, the village, the weather, her friends. But she did not want to return to them.

Sarabjit was still living in Ontario in early 2003. In November 2002, she and her parents received the immigration papers in the mail. They must attend a deportation hearing. The ruling came early in the new year: they were ordered to leave Canada.

Many of the Punjabis subpoenaed to testify in the prosecution of Sukhwinder Dhillon used the opportunity to claim refugee status—17 of them in all. One who was unable to do so was Dhillon’s fourth and final wife, Sukhwinder Kaur. She was never called over as a witness, and never made it to Canadian soil. She had married Dhillon to get into Canada. But that union was null and void when it came to light that he was already married at the time of the wedding. So she married another Indian man who lives in Canada—Vancouver, British Columbia—in the hope of making

it overseas. In the summer of 2002, she sat in her taupe-colored house in the village of Dhandra, the room darkened to beat suffocating heat, fans churning to circulate the air. A journalist paid her a visit. Sitting on her bed, she began to cry. It’s the visa. It’s not fair. She was supposed to be granted one several years ago, and now her application was being held up again, even though she has a new husband in Canada. She looked like a broken woman, but she kept her focus on the goal. No photos, she told the journalist, and no comment on anything—unless they can get her a visa to Canada. Then she would deal. Talk to the lawyers, she said, the Hamilton detectives. Here is my passport. Look at it! They promised me a visa if I cooperated in the Dhillon case. She rose from the bed, left the room, a silhouette in the darkened hallway, then disappeared.

it overseas. In the summer of 2002, she sat in her taupe-colored house in the village of Dhandra, the room darkened to beat suffocating heat, fans churning to circulate the air. A journalist paid her a visit. Sitting on her bed, she began to cry. It’s the visa. It’s not fair. She was supposed to be granted one several years ago, and now her application was being held up again, even though she has a new husband in Canada. She looked like a broken woman, but she kept her focus on the goal. No photos, she told the journalist, and no comment on anything—unless they can get her a visa to Canada. Then she would deal. Talk to the lawyers, she said, the Hamilton detectives. Here is my passport. Look at it! They promised me a visa if I cooperated in the Dhillon case. She rose from the bed, left the room, a silhouette in the darkened hallway, then disappeared.

Other books

Harry the Poisonous Centipede by Lynne Reid Banks

Playing for Hearts by Debra Kayn

Elizabeth Bennet's Excellent Adventure: A Pride and Prejudice Vagary by Regina Jeffers

Gravedigger's Cottage by Chris Lynch

Skipping Christmas by John Grisham

Dead Girls Don't Cry by Casey Wyatt

Savage Chains: Captured (#1) by Caris Roane

Humpty Dumpty: The killer wants us to put him back together again (Book 1 of the Nursery Rhyme Murders Series) by McCray, Carolyn, Hopkin, Ben

Dark Journey [Ariel's Desire 2] by Candace Smith

Passion Over Time by Natasha Blackthorne, Tarah Scott, Kyann Waters