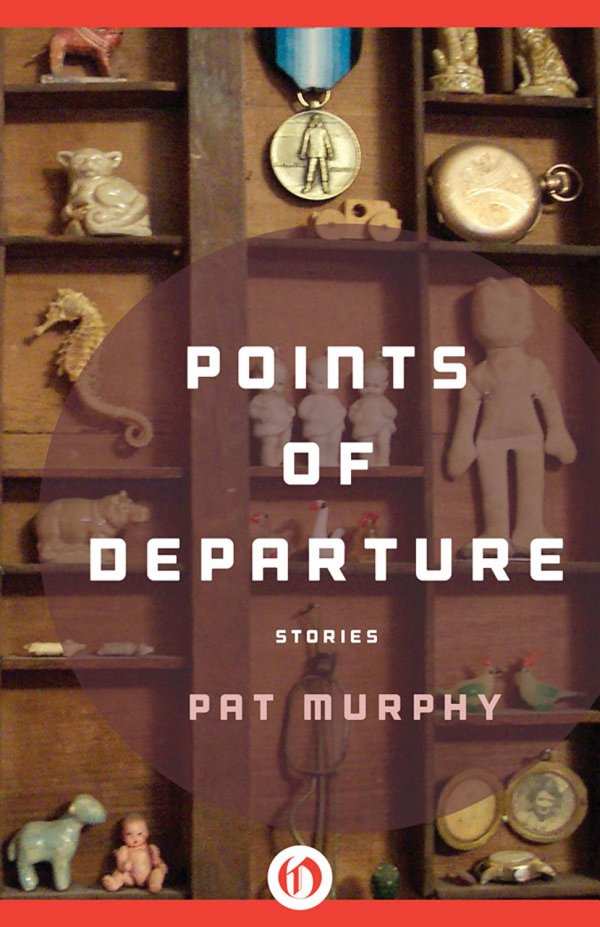

Points of Departure

Read Points of Departure Online

Authors: Pat Murphy

PRAISE FOR THE WRITING OF PAT MURPHY

PRAISE FOR THE WRITING OF PAT MURPHYThe Falling Woman

Winner of the Nebula Award for Best Novel

“A lovely and literate exploration of the dark moment where myth and science meet.” —Samuel R. Delany

“Murphy’s sharp behavioral observation, her rich Mayan background, and the revolving door of fantasy and reality honorably recall the novels of Margaret Atwood.” —

Publishers Weekly

“Murphy’s convincing

modern setting is a marvelous foil for her frighteningly alien Mayan ghost, and the archeological material, besides being fascinating in its own right, is put to excellent use in the plot.” —

Newsday

The City, Not Long After

“A grand adventure.” —

San Francisco Chronicle

“In Ms. Murphy’s skillful hands, the showdown between art and power takes on mythic dimensions… . No one comes out of this

confrontation unchanged, including the reader.” —

The New York Times Book Review

Points of Departure

“There is something of Borges’s absurdist fables and of the fey, fog-haunted feel of Celtic myth to [

Points of Departure

]. This collection reverberates with the sound of the author’s unmistakable voice, a poetic blend of the everyday and the never-never.” —

Elle

“Brilliant, passionate, and dangerous

as only the clearest visions can be … Murphy creates seamless blends of ideas and emotions, holistic works where genres mingle so the reader does not stop to ask if this is sf, fantasy, or horror… . These tales unite the power of a force of nature with the subtlety of the human heart.” —

Locus

Wild Angel

“A charming adventure.” —

The Denver Post

“A delightful cross-genre mix with elements of

mystery, western and fantasy/adventure infused with a feminist sensibility.” —Rambles.net

“Faithful to the spirit of Edgar Rice Burrough’s Tarzan tales and Rudyard Kipling’s

Jungle Book

, this [is the] story of a young girl’s courage and resourcefulness.” —

Library Journal

Adventures in Time and Space with Max Merriwell

“Set on a cruise ship that blithely steams through the Bermuda Triangle,

this savvy romp buttresses its nonstop action with quantum-mechanical insights into the nature of the universe and postmodern noodling about the nature of writing and reading.” —

The New York Times Book Review

“This cerebral equivalent of a roller-coaster ride … is replete with absorbing ponderings on the nature of reality and the nature of the novel… . The questions of who is in charge, who is

real and whether the answers to those questions matter will leave readers pleasantly dizzy.” —

Publishers Weekly

“A paean to the potentialities of imagination, foaming quantum uncertainties, and the sheer plasticity of human reality.” —

Analog Science Fiction and Fact

The Shadow Hunter

“The clash of prehistoric shamanic traditions with future technology makes for a gripping tale—the first novel

written by this Nebula Award-winning author.” —

Publishers Weekly

Stories

Pat Murphy

For Dad, with love,

and

as always, For Richard.

On a Hot Summer Night in a Place Far Away

A Falling Star Is a Rock from Outer Space

On the Dark Side of the Station Where the Train Never Stops

Recycling Strategies for the Inner City

Kate Wilhelm

S

TUDENTS OFTEN ASK

, how can I develop a good style, and the answer is simple: Honor thy mother and father, eat your carrots, don’t step on the cracks in the sidewalk, and as surely as your hair grows and your fingernails lengthen, your style will develop. The companion question is: What should I write about? And another simple answer comes to mind: Don’t fret; your themes

will find you.

If the novel is a doorway opening to another universe, then the short story is a window through which we can glimpse a contained piece of another world. In her novel

The Falling Woman

, Pat Murphy opened wide the door into modern Mexico, as well as ancient Mayan times, and invited us in to walk and talk with compelling characters.

In the stories in this collection we get glimpses

of other strange and wondrous places and people. But a window works both ways: Not only can we see through to the other side, but from there we can look back and perceive the emerging writer. And this writer has eaten her carrots and done honor to her parents. Her style is emerging strongly, lucid, often lyrical, and uniquely hers. Her themes and concerns have discovered her and are demanding a

voice.

From the earliest story in this collection, one recurring theme is undeniable: the meaning of personal power and talent. In “Touch of the Bear” power is denied, then accepted. It is shown to have a Shadow side that is both exhilarating and threatening. To carry the Jungian examination just one step further, we can see the strong line of continuity from past to present most clearly in this

early story: The power is derived from sources so ancient they are the very basis for the collective unconscious, pure archetypes. The idea of the past as a dynamic force in the recent surfaces again and again. This early story states the theme of creative power blatantly; the subtlety of the later stories is not yet developed, but the meaning is clear from the start. Again and again Pat comes

back to the quandary that the possession of talent, of power, presents.

In “Don’t Look Back” the question arises: Isn’t talent enough to free one from a deterministic universe? In “Clay Devils” the creative power is recognized and dealt with in quite a different manner as a simple peasant artist comes to understand the high price creativity may exact.

“Prescience” is a lovely story with a marvelous

sustained tone that is a pleasure to read, and it deals with the question: If you knew what the future holds, couldn’t you arrange your life better? This is a late story, with a subtle treatment of the same theme, with yet another approach and without despair. In it Katherine of the story is accepting of her strange talent; she uses it honestly and openly and takes whatever consequences that

follow with good humor.

Not so in “Bones” where the power is manifest in a giant among humans, but a giant who must suffer torment because he cannot find the outlet his gift demands. To have such power denied through any means can be dangerous; instead of liberation there may be destruction of the self.

Another of Pat Murphy’s recurrent themes is the encounter with the stranger, the other who

does not fit in, who is alien either literally or metaphorically. The stories in this group mature from the earliest, a simple wish fulfillment, through the alien as phantom lover, to a more complex treatment as in “In the Islands,” where the alien is web fingered and ocean-bound, and the human is very human indeed. Nick in this story, and Michael in “Orange Blossom Time” react to the other with

suspicion, awe, envy, resentment, all the human emotions that such an encounter must excite.

In “A Falling Star Is a Rock from Outer Space,” a middle-aged, lonesome woman encounters an alien in a story that could have turned into just another horror story.

Pat chose compassion instead of special effects to make the story rise above such easy categorization. And compassion is the key word for

the very fine story “On a Hot Summer Night,” in which a lusting Mexican hammock vendor meets a strange woman who cannot get warm. The usual xenophobic treatment of the alien, the other, is missing in both of these stories; instead, compassion and acceptance bring about peace, the filling of a void, or even redemption.

The final story in this series is the highly acclaimed, award-winning “Rachel

in Love,” which needs no further introduction here, of course.

One of the thematic threads interwoven throughout Pat’s novel

The Falling Woman

was the relationships within the triangle of mother/father/daughter. The complexity of parent/child relationships, of male/female relationships surfaces again and again in her work, not stridently as in the most radical feminist mode, but thoughtfully

and even painfully. The man searching for his father and the Yeti, the girl whose sister ran way to space to escape domestic battling, the woman whose clever fingers created devils that turned her husband into a devil, these are all very human problems, not necessarily feminist concerns, except that feminism embraces all humanity, all its relationships.

What makes a man sacrifice his daughter

to achieve a material success? Her revenge is to keep him imprisoned in the box, one of the “Dead Men on TV.” What makes a man eschew a real woman for a vegetable wife? Her revenge is to teach him that even turnips have teeth.

Explanations are not necessary; it is enough to have seen this situation unravel, or that one. We are given the vision; we can ponder the reasons.

And the “Women in the

Trees,” a frightening, haunting story, doesn’t try to answer the questions either, but only poses them. The live oaks were old when the landlord’s grandmother was young. They have always been there, have always held a community of women who escaped, have always sheltered them; the continuity is intact. This collection is like a house of many windows, and this is one of the encapsulated worlds visible

from within, ugly, forbidding, mysterious, real. Our world, after all.

These stories span a ten-year period, hardly a beginning to what will surely be a long career. Pat is flexing her muscles; her grasp is growing ever surer, her reach more ambitious, her vision sharper. She is still staking out a territory, and she has found a voice. Read and enjoy these stories, and anticipate, as I do, the

new vistas to be revealed as she opens more windows, opens the door wide, and invites us in.

October 1989

I

STAY UP LATE

each night, watching my dead father on TV. Tonight, he’s in

Angels of the Deep

, a World War II movie about the crew of a submarine. My father plays Vinny, a tough New York kid with a chip on his shoulder.

He was about twenty when the movie was made; he’s darkly handsome, and an air of danger and desperation surrounds him.

I’ve seen the movie half-a-dozen times before,

but I turn on the TV and curl up in my favorite easy chair with a glass of bourbon and a cigarette. The cream-colored velvet that covers the easy chair’s broad arm is marked with cigarette burns and dark rings from other glasses of bourbon on other late nights. The maid told me that the stains won’t come out, and I told her that I don’t care. I don’t mind the stains. The rings and burns give

me a record of many late nights by the TV. They give me a feeling of continuity, a sense of history: I belong here. The television light flickers in the darkened room, warming me like a fire. My father’s voice speaks to me from the set.

“Can’t you feel it?” my father says to another sailor. His voice is hoarse; his shoulders are hunched forward, as if he were trying to make himself smaller. “It’s

all around us—dark water pushing down. Trying to get in.” He shivers, wrapping his arms around his body, and for a moment his eyes meet mine. He speaks to me. “I’ve got to get out, Laura. I’ve got to.”

On the TV screen, a man named Al shakes Vinny, telling him to snap out of it. Al dies later in the movie, but I know that the man who played Al is still alive. I saw his picture in the newspaper

the other day: he was playing in a celebrity golf tournament. In the movie, he dies and my father lives. But out here, my father is dead and Al is alive. It seems strange to be watching Al shaking my dead father, knowing that Al is alive and my father is dead.