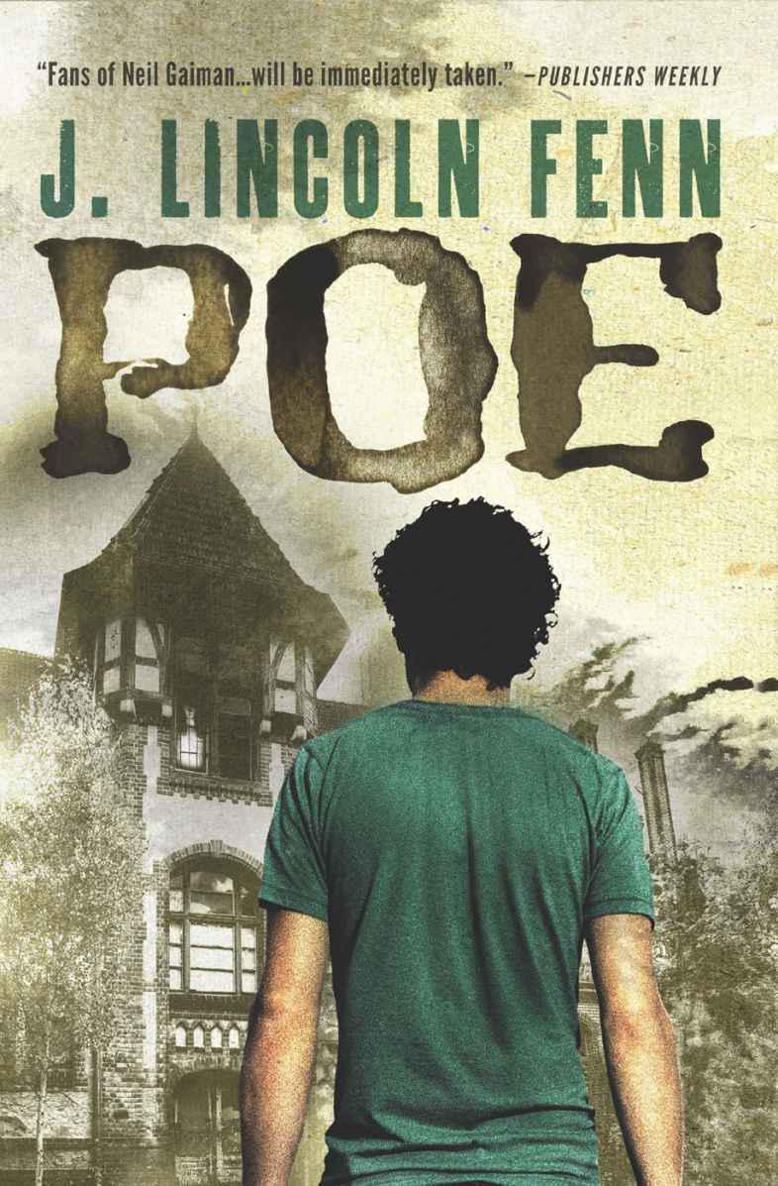

Poe

Authors: J. Lincoln Fenn

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is coincidental and not intended by the author.

Text copyright © 2013 Nicole Beattie

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express written permission of the publisher.

Published by 47North

P.O. Box 400818 Las Vegas, NV 89140

ISBN-13: 9781477848166

ISBN-10: 1477848169

Library of Congress Control Number: 2013940591

For my parents, the living and the dead.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER NINE: DANIEL’S NUMBERS

CHAPTER TEN: DEVIL IN THE CORNFIELD

CHAPTER FOURTEEN: DANIEL’S ESCAPE

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN: AFTER I’VE GONE

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN: THE SECRET BOOKS

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE: MAGIC SQUARE

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO: NIGHT VISION

CHAPTER TWENTY-FIVE: THE GREENHOUSE

CHAPTER TWENTY-SIX: LIFE SUPPORT

CHAPTER TWENTY-SEVEN: A HARD TRADE

Dearest friend, do you not see

All that we perceive

Only reflects and shadows forth

What our eyes cannot see

.

Dearest friend, do you not hear

In the clamor of everyday life

Only the unstrung echoing fall of

Jubilant harmonies

.

Vladimir Soloviev, Russian Gnostic and philosopher, 1892

We people are the children of the sun, the bright source of life; we are born of the sun and will vanquish the murky fear of death

.

Maxim Gorky,

Children of the Sun

, 1905

PROLOGUE

C

link

. it sounds like someone just put a penny in a jar. Unfamiliar voices in the distance, fuzzy and hard to pinpoint. My ears are ringing. Damn, why is it so cold? There’s something else too, a putrid stench, like shit and rotten pizza mixed together.

Focus

.

I was breathing water—it was cool and felt good in my lungs. I was drowning, dying, and strangely I didn’t seem to mind. And there was a woman in the water—ice-blue skin, blond hair floating like tendrils of seaweed. She wanted to tell me something, and I could see a solitary word bubbling from her frigid lips—my name, Dimitri. Then something else, something

important

, but I can’t pull the memory to the surface, and it is so cold, so very, very cold.

Gradually the ringing in my ears stops. My hearing starts to clear. There’s a whoosh of something like a fan, and a refrigerator hum. I try to open my eyes, but they refuse.

Clink, clank, clunk

. Someone is humming.

Humming?

Then a low voice. “So my wife is, like, you need to take a shower before you come home from work, you smell like cadavers, and

I

said, you don’t seem to mind cashing the checks.”

A lighter voice, feminine. “Um-hum.” Obviously not listening.

“She can’t say anything then, ’cause she’s got a new Gucci purse she doesn’t want to tell me about. Like I don’t read the credit card statements—

hey

, do you mind turning that thing off while we’re working?”

A sigh, then a click. “It keeps me focused.”

“Can’t believe your iPod still works after it fell in that guy’s stomach. You’d think the acid would have shorted the battery.”

“Waterproof case. I did have to get new earbuds though.”

Deep-voice guy snorts with laughter. Then a sudden intake of breath. “Damn, have you ever seen a stab wound this deep before? The knife splintered her rib.”

Thumpity thump thump. My heart starts to beat. It’s cautious, like it’s not sure whether there’s much point, but methodically plods along anyways. Each throb pushes more of the fizzy darkness aside with a familiar staccato rhythm that’s reassuring. Suddenly, every nerve in my body kicks in, tingling with a fiery determination—it’s a rush. I realize I’m naked. I’m lying on something cold, metallic, and decidedly uncomfortable. I try a breath, and the air burns my lungs, but they seem functional.

“What kind of knife would do that?”

“A very sharp one.”

“Ha-ha, very funny.”

Pause.

“Check out the spleen. It looks like something was

eating

it.”

“Maybe she had cats. Cats are heartless.”

“Cats are not heartless,” replies the feminine voice.

“When’s the last time you heard about a dog eating its dead owner? Never.”

Snap, crack, clink

.

My eyelids finally flutter—a fuzzy light glows behind something white and cottony. I gather my jangling neurons, point them at my right arm—

Move, arm, move

—and manage to jerk at the sheet that’s covering me. A new chemical stink wafts by—formaldehyde—and above me a bright, round fluorescent light nearly blinds me. I slowly turn my head; it feels like my brain is sloshing inside my skull, and it takes a moment for the dizziness to clear enough for me to see.

A man and a woman in surgical scrubs stand in front of a gray naked body. Bright red blood spatters their sleeves and gloves. The man holds a large pair of shears, also covered in blood, and the woman has a white dangling earbud that trails from beneath her surgical cap to a bulge in her right front pocket. They both stare, perplexed, into the abdomen of what appears to be the corpse of a fiftyish woman; her frizzy gray hair is badly permed, and she stares at me with the glossy eyes of a dead fish. A flap of thick, yellowed, and fatty flesh hangs from her waist, and I can see blue veins crisscrossing the tissue, while some kind of white, viscous liquid oozes onto the linoleum floor. A bloody heap that looks like raw hamburger rests on a hanging metal scale. Ten pounds.

I’m in a morgue. My stomach heaves, but there’s nothing to throw up. My body is completely drained. Empty.

“Hey, did you do that?”

“What?” Something squishes.

“Drowning dude’s sheet is off.”

“Well why don’t you go fix that? My hands are a little tied, if you know what I mean.”

The woman mutters, “I’m not some kind of first-year resident…”

A scream builds in the back of my throat and dies there.

Footsteps softly pad across the linoleum floor. I can feel the rough sheet being pulled back up and over my feet, my legs, my chest. I need to move—I need to move

now

. Somehow I turn my head, look at the woman in scrubs directly in her eyes. Blink. I open my mouth, and a small rush of water pours out.

“Holy shit!” She jumps back, knocking the scale. It swings like a pendulum, and the hand on the dial swerves wildly as the bloody heap slides to the floor with a wet plop.

My eyes roll toward the back of my head, and I reach one hand out, grasping nothing. Suddenly I remember what the woman with the ice-blue skin said in her strange, watery voice.

“

Dimitri. He’s coming. He’s coming for

you.”

Then the darkness wells up, envelops me, and I’m gone again.

HALLOWEEN

Twenty-four hours earlier

CHAPTER ONE: NEW GOSHEN

T

here’s not a lot of opportunity to get creative with obituaries. Take Mrs. Porrier, aged eighty-five, an elementary school teacher who committed suicide by locking herself in the garage of her four-bedroom colonial house with the car running.

She had terminal pancreatic cancer, but that’s not the point. The point is that the most interesting part of her life—the moments leading up to her death—I can’t write about. I can’t write that she got the car keys out of the brown leather bowling ball bag cherished by her husband—Mr. Porrier, otherwise known as “Doc” to his league—and opened the familiar latch of the screen door. That she pressed the yellowed plastic button of the electric garage door opener, got into the car, and pulled the heavy door of the ancient but still functional Cadillac behind her—the scent of cigarette smoke still in the carpeting, although her husband had quit smoking ten years before. I can’t write that she rolled up the windows by

hand

—nothing automatic in that car—and started the engine. And the moment before her eyes got heavy, when she still could have gotten out of the car but didn’t, the moment she decided

enough

, I can’t include in her obituary.

Instead, I have to write the mundane, perfected-life details. She taught school for forty years. She is remembered by her grandchild Harris in Colorado, her daughter Stella, also a teacher, in California, and her beloved husband, who served two years in the Korean War. She enjoyed knitting, horticulture, and baking. She died of pancreatic

cancer. I reduce her to a palatable bit of print, ready to be absorbed, digested, and quickly forgotten.

Christ, I wish I didn’t take this shit so seriously.

I try to avoid the newspaper office in the flatiron building on New Goshen’s Main Street as much as possible—probably because I’m supposed to work there. So over the past year I’ve suffered periodic intestinal episodes from bad sushi. My car has a habit of being borrowed by my (nonexistent) roommate, or the tires are flat, or the battery needs a jump. I’m susceptible to migraines, increasingly bad episodes of asthma, and my back needs regular appointments with a chiropractor, who keeps changing my appointment times. As long as the deadlines are met, Mac, the editor (who really lets themselves be called Mac anyway?), doesn’t threaten me too much with firing, which is bullshit anyway because there aren’t many people in this town who could string together one sentence, let alone two.